Astrobiologist Dr. Bruce Damer may have revolutionised our understanding of how life on Earth began. In 2017, his work with biophysicist David Deamer on the Hot Spring Hypothesis was splashed on the cover of Scientific American—a breakthrough expedited by his experiences with ayahuasca. Now, he is forging a new path for research and creative practice as a co-founder of the Center for MINDS, which seeks to pioneer the science of breakthrough insights for humanity’s greatest challenges. Psychedelic Alpha spoke with him about the nonprofit’s mission and how it is picking up the “abandoned thread” of research into psychedelics as catalysers of creativity and innovation.

Dr Bruce Damer’s career spans computing, space exploration and the science of life’s beginnings. The Canadian-American scientist began his career in the 1980s by developing early personal computer interfaces, then pioneered multi-user virtual worlds in the 1990s. Since 2000, he has supported NASA and the aerospace industry on simulations and spacecraft design, including one of the first technical scenarios for taking people to the surface of an asteroid.

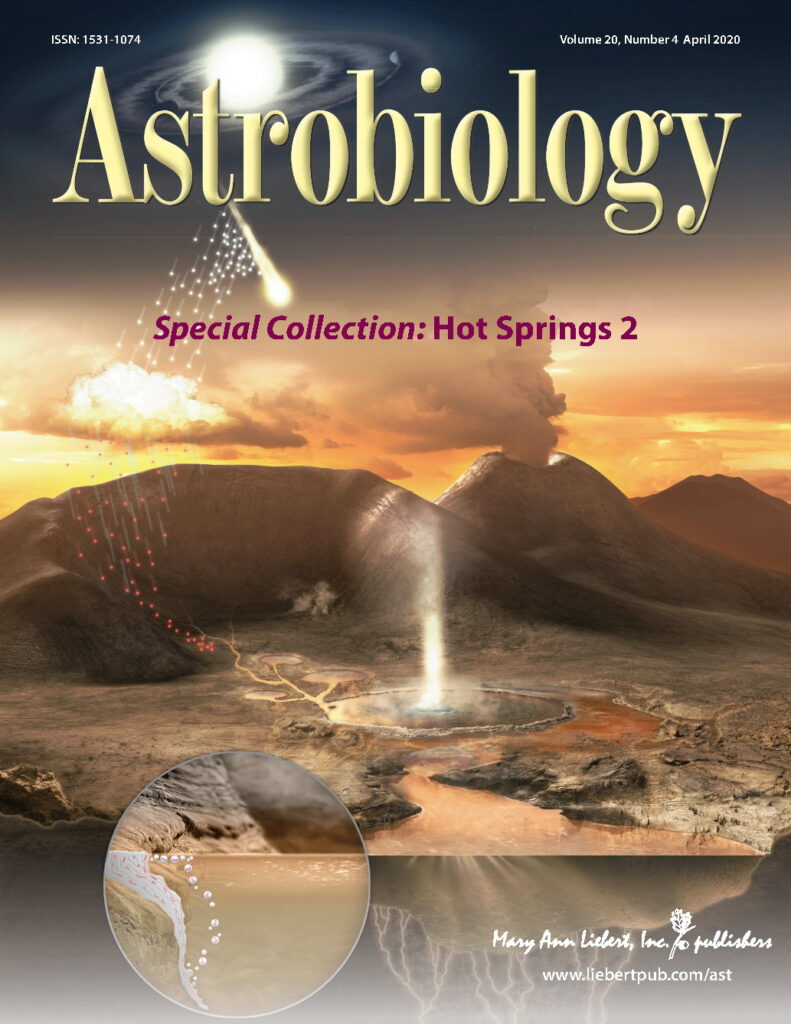

But Damer’s most significant work may be in astrobiology. As an associate researcher in biomolecular engineering at UC Santa Cruz, he collaborated with David Deamer to develop the Coupled Phases Scenario for the origin of life. In 2020, they elaborated on this premise by publishing the Hot Spring Hypothesis for an Origin of Life in the journal Astrobiology—a testable model explaining how the first cells could have emerged from fluctuating volcanic pools. Damer holds multiple roles, including chief scientist at the BIOTA Institute as well as associate of the NASA Astrobiology Centre. He also curates extant archives of historical psychedelic figures including Timothy Leary and Terence McKenna.

Now, as co-founder of the Center for Multidisciplinary Investigation into Novel Discoveries and Solutions (MINDS), Damer is applying his diverse professional experience to a new challenge: using psychedelics to catalyse breakthroughs in science, technology, design and leadership.

Origins

Damer described himself as a “distinctly non-psychedelic kid” who avoided drugs including cannabis and even caffeine due to sensitivity.

“I was a little bit on the spectrum, pretty quiet and internal in a lot of ways,” he said. “And so, psychedelics or drugs of any sort were never very appealing. I thought… maybe they’ll mess up the visionary machinery that I already have. I don’t want to corrupt my system—to shatter this fragile eggshell mind of mine.”

Yet he had a vivid visual imagination from a young age, experiencing “technicolour object-filled landscapes” in hypnogogic states behind closed eyes.

“When I was 9 or 10 years old, I began having regular access to these states, and they became my own private TV channel,” he said, adding, “I discovered that the signals would come in much more clearly if I could somehow turn down my mind.”

His first psychedelic experience came at the “rather advanced age” of 37 after meeting Terence McKenna, who provided him the source for a heroic dose of psilocybin mushrooms. Years later, beginning in 2011, Damer participated in a series of yearly ayahuasca ceremonies in the Amazon—an experience he described as a “complete life-changer”. The initial intention of these sessions was to heal birth trauma he experienced as an adopted child.

As his healing journey progressed, he gradually began to believe that perhaps these insights could extend beyond psycho-spiritual realms into his professional work. The timing was advantageous—at UC Santa Cruz, Damer and Deamer had reached an impasse in their origins of life research.

“We had come up to a point in the lab where we could form polymers from the building blocks of RNA, and through wet-dry cycling under simulated hot spring conditions get them encapsulated into lipid compartments forming ‘protocells’—candidates for the most primitive ancestors of living cells. While this was a pretty significant result, we had not kickstarted anything resembling evolution or something like genetic material to encode traits. We just couldn’t see a path forward to any of that.”

Facing this formidable mental block, Damer recognised he needed a “huge leap in mental capacity” to get beyond his constrained thinking, and seek solutions in a “novelty-generating complexity landscape”. In 2013 he returned to Peru for another set of ayahuasca sittings, this time applying the amplified cognition experienced on the psychedelic tea to his scientific problem.

“Over a decade of psychedelic exploration after my first trip in 1999, I had found that I could open up realms that were inaccessible to my waking state of consciousness,” Damer said. “And by 2013 I was familiar enough with these realms that I could go in and creatively engage in psychedelic space, in my case with a really tough problem in science.”

That journey found Damer “in a warm, little hot spring pool on the ancient Earth after traveling back metaphorically through four billion years”.

“Searching for protocells, I found my way into that pool. And then, surprisingly to me, I died and was reborn as that first protocell attempting its own division, at the very threshold of the living world.”

“As the tearing apart of the protocell was underway, I looked around and within my temporarily transformed body, I witnessed interacting polymers, and the code of life being read and written. The most confusing part of this vision was that the protocell division failed, and instead of birthing its twin, a black, dead compartment floated away. It was a huge mystery. It wasn’t a solution to the origin of life but instead it catalysed a new perspective and a reframing of the question.”

“Months later I realised that reframing, telling myself: ‘Don’t look at the pathway to the origin of life as solely a process of building from simple molecules to complex ones. Look at it from the very moment that the first cells become able to divide and work backwards from that point.’ It was a huge new insight but merely a first step.”

Realising the full potential of this epiphany required patience. It wasn’t until after a later “endo” trip triggered by a pranayama breathwork session that he experienced his eureka moment. (Damer distinguishes between “endogenous” or “endo” trips—heightened states of consciousness originating naturally from within the body—and “exogenous” or “exo” trips induced through psychoactive or other stimulants.)

“Three months later, I had an endo trip—an hour-long download—and a fully formed insight landed.”

“For me, there were four initial stages to this insight: first, the priming of the question through research, next the psychedelic-assisted or catalysed visionary experience, an incubation period, and then came the endo trip, initiated by breathwork, where it all was able to flow in full complexity.”

“The fifth stage was of course to translate these visionary insights into science—from my abstract sketches and notes into chemistry, and then into testable experiments in the laboratory and out into the field at hot springs around the world. The sixth and seventh stages came through peer review and publications and the resultant pushback and, hopefully, replication by colleagues.”

“I have been fortunate, through the unwavering support of my colleague Dave Deamer, to contribute to a breakthrough that has swept the field of astrobiology,” Damer continued. “While Dave brought in the wet-dry cycling chemistry of protocell formation in hot springs, my big picture visionary view contributed the full cycling evolutionary system and I attribute that to a combined use of ayahuasca and mindfulness practices.”

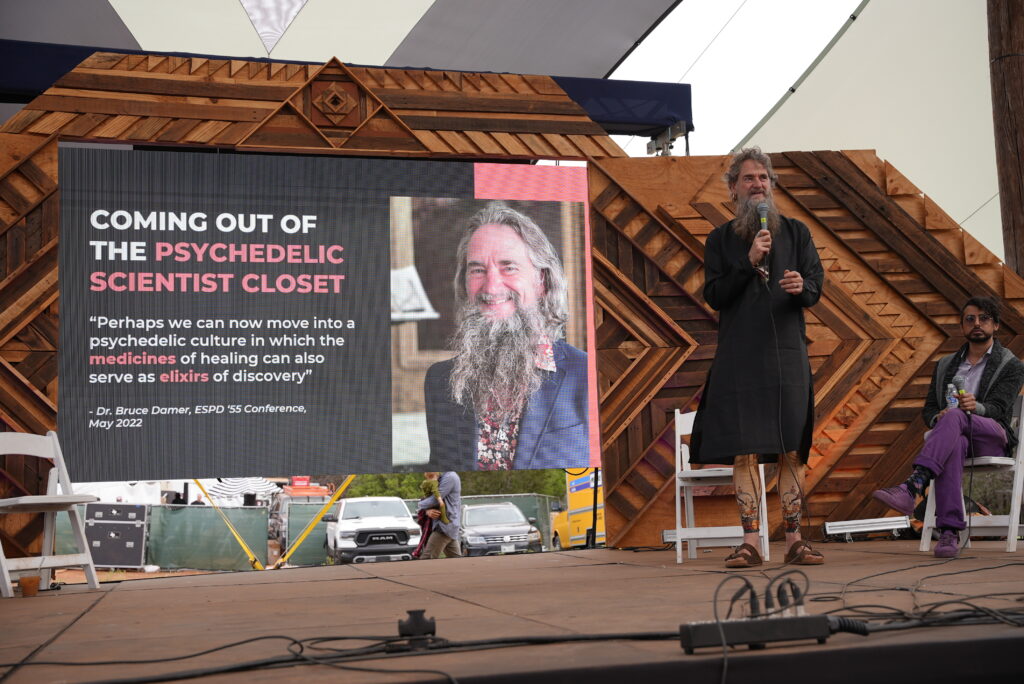

Coming out of the closet

Damer and Deamer’s work was featured on the front cover of the journal Astrobiology in 2020. By then, their wet-dry cycling hot spring scenario was being adopted by other laboratories worldwide.

But this success presented a dilemma: should Damer “come out” as a psychedelically-inspired scientist and potentially risk all of this progress? Other scientists had chosen to stay out of the limelight. In the case of Kary Mullis, the inventor of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method—the basis of gene sequencing—he only chose to talk about his creative use of LSD after receiving his Nobel prize in 1993.

Damer felt his use of psychedelics for scientific work could be valuable to share with others. Yet when in 2016 a major magazine got in touch with him to do a profile, he was reluctant to attach his name to it.

“Halfway through the interview I said, ‘I can’t do this’ because I was serving on NASA review panels and we have our own active grant applications, and this disclosure could risk our science.”

In 2022, Dennis McKenna invited Damer to present at the Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs (ESPD55) symposium in Dorset, UK. After deliberating for a few days, he offered to give a talk titled ‘It’s High Time for Science: Psychedelics as Tools for Scientific Discovery’ where, in May of that year, he finally revealed the key practices behind his science.

“I decided to come out of the psychedelic scientist closet three years ago… to serve as an example for other scientists and creative people, including problem solvers, technologists, designers and those in challenging leadership jobs,” Damer said. “I also felt it was important to return scientific studies into the catalytic creative flow that’s opened up in these states.”

He added: “When I looked into this, I found that along with therapeutic uses of psychedelics, they had also been studied by Willis Harman and Jim Fadiman and others in the mid-1960s as tools for problem solving. I was shocked that this compelling thread had been dropped and not picked up again in over a half century.”

Forming MINDS

Two months after his ESPD talk, he met investor Ford Smith and non-profit chair Sylvia Rzepniewski in Austin, Texas. Both were very interested in Damer’s work and how it had been expedited by the psychedelic experience. In 2023, they incubated the Center for MINDS as a non-profit out of their venture fund, and publicly launched it at the Texas Eclipse Festival in April 2024.

“We modelled MINDS roughly on MAPS,” Damer said. “We’re both multidisciplinary, we’re both into investigation—but rather than medical applications, we decided to focus on novel discoveries and other transformative solutions for the world arising through psychedelic-catalysed insight and other practices.”

“We posed the question: is it possible to artfully combine these practices to help scientists, engineers, designers and leaders really crack hard problems and come up with beautiful solutions?”

“Technically-oriented people often reach points where they just can’t get any further,” Damer told Psychedelic Alpha. “For me, in the chemistry of the origin of life, it was what happens to trillions of polymers within billions of protocells cycling in a hot spring pool… where do they go next? For someone working, say, in mitigating the effects of climate change, a mind-bending problem might be: ‘How should we build now to account for sea level rise in fifty years?’”

Damer offered a view of how psychedelics might work, at least for him: “Perhaps they soften my mental blocks or quiet my nervous mind and just let everything flow more freely.”

He advised that solutions did not come on a first trip or even after several journeys.

“It may take several sessions. For me, it was 25 sittings involving personal work with ayahuasca before I felt clear enough to bring in the science. But then there came an opening, and a remarkable return, after I had set the intention that I wanted to work on this origin of life problem.”

“Perhaps through psychedelics and other consciousness practices you open up to what Dean Simonton calls a ‘free association storm’. Simonton is a great thinker and writer who researches how genius works. His books are wonderful—they’re not psychedelics—but they form one of the pillars of what we’re doing at MINDS.”

Damer is not alone in crediting psychedelics with seminal discoveries. Francis Crick reportedly used LSD when working on double helix structure of DNA (or perhaps later when gene expression was being tackled). Computer scientist Douglas Engelbart, inventor of the computer mouse and graphical interface in the 1960s, attributed some of his creative powers to psychedelic experiences.

“There’s a long history of this—we’ve all heard about Steve Jobs’s use of LSD being primarily important in his life,” Damer said. “Bill Atkinson credited acid for helping him in creating HyperCard, a game-changing piece of software that presaged the World Wide Web.”

“The mathematician Ralph Abraham, another exemplar, has argued that psychedelics were instrumental in the emergence of chaos theory,” Damer added. “The principles of chaos mathematics and dynamical systems, among their many other uses, are invaluable to the computer models used to study climate change, so it is no exaggeration to say that this field of science is extremely important to our future.”

Damer noted that, in recent years, there has been renewed interest and research in three primary psychedelic paradigms: Indigenous and cultural use; personal growth and expression; and therapeutic medical applications. For Damer, the Center for MINDS will focus on re-opening a “fourth path” of using psychedelics to enhance human cognition and creative problem solving.

The idea was first floated in the mid-1950s by psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, writer Aldous Huxley and neuropsychologist John Smythies with a proposed study titled ‘Outsight’. Together they sought to investigate the effects of mescaline and LSD on the intelligentsia of the day, with participants including Carl Jung, Albert Einstein, A. J. Ayer and Graham Greene. But funding for the project never materialised and the effort was abandoned.

But in 1966, a pilot study titled ‘Psychedelic Agents in Creative Problem-Solving’ led by Willis W. Harman was published just as LSD was criminalised. It found that 66% of the 24 study participants reported enhanced creative problem solving under the influence of LSD or mescaline in a structured and supportive environment. But as the early stages of the War on Drugs took hold, this line of enquiry was discarded.

The Center for MINDS seeks to pick up this “abandoned thread of psychedelics as creative catalysts,” in Damer’s words, and connect people who use mindfulness practices and psychedelics to solve complex problems.

“Of course, psychedelic tools were never completely abandoned by artists and other creative people,” Damer said. “But with professionals it was carried out completely out of sight—under the table, if you will.”

The Center for MINDS will fund research including clinical studies, retreat practice groups and testing protocols, eventually publishing empirical findings to ground mentorship and training programmes.

“As a research organisation, we can also offer micro grants to allow, say, a therapeutic psychedelic practitioner to do some data collection that they just don’t have time to do, to hire an assistant or employ tools,” Damer said. “We know that after a psychedelic-assisted therapeutic session, many people experience an ‘afterglow’ effect which can carry heightened mental capacities. By following up with these patients, we could find out how the practice benefitted or didn’t benefit their working lives.”

The MIND FLUX study

In partnership with Austin-based integrative health company Ways2Well, the MIND FLUX study represents the centre’s first sponsored clinical research. Led by Dr Manoj Doss and Dr Greg Fonzo at the University of Texas’s Charmaine & Gordon McGill Center for Psychedelic Research and Therapy, the study tests whether psilocybin can enhance processing fluency—the brain’s ability to organise and make sense of complex information, which is thought to be instrumental in ‘aha’ moments.

The study will run in three phases. First, researchers are surveying technical professionals and creatives who have used psychedelics to solve problems. Second, they’ll conduct clinical trials using fMRI brain scans and cognitive assessments to measure psilocybin’s effects on fluency, memory and creative thinking. Third, they’ll design research to test whether these effects translate to breakthroughs in professional settings.

Most psychedelic research targets therapeutic applications for disorders. MIND FLUX shifts the focus to healthy individuals and breakthrough thinking to examine the neurological processes underlying psychedelic creativity. Specifically, it will examine the hippocampus’ role in generating or suppressing episodic memory during creative states.

Doss reports that the study will measure creative problem-solving through tasks assessing lateral thinking and novel ideation. It will examine whether altered states help encode and retain insights more effectively to determine if these effects can catalyse meaningful breakthroughs in science, design or leadership.

The Center for MINDS seeks support and input from thought leaders across business leadership, artificial intelligence, finance, science, design and technology in the hope of expanding research into how these tools might accelerate creative breakthroughs. Damer is convinced that they will increase our chances of solving challenges surrounding the polycrisis that humanity faces, including existential threats such as climate change, biodiversity collapse, pandemic preparedness, resource scarcity and geopolitical instability.

Damer is also interested in finding out whether the empirically supported use of psychedelic-catalysed creativity can positively impact those who influence legislative and regulatory change.

“Just maybe these people could be some of ‘the others’, as Timothy Leary described the psychedelically ‘experienced’. They could influence policy in a very, very significant way. After all, business leaders make major campaign donations and they build companies that change the future, perhaps more than politics does.”

“In the year 2000, if you asked a group of 10 tech or other entrepreneurs if they had psychedelic experiences or they felt that it was helpful for their lives or their business, you might find one that said they went to Burning Man,” Damer said. “If you ask them today, you will get 7 to 8 of them say that they are very experienced in the psychedelic space, and they rely upon it for their healing and perhaps also their ‘revealing’.”

“In a sense we have crossed over into critical mass—the tipping point where pretty much every business person you know below a certain age, even above a certain age, is psychedelic-positive.”

“Perhaps they have never supported therapeutic research, but are very interested in the creative aspect,” Damer said. “Today, most professionals are very curious, and not dismissive or critical. This reality is a big opportunity to obtain support for this work.”

“If those toiling in the centre of capitalism, entrepreneurs, visionaries and business leaders, scientists, and designers, stand up and say, ‘Hey, I’ve experienced not only healing, but tremendous powers of revealing with these tools,’ it would valorise them into society in a whole new way.”

He continued: “If we can validate through science and then valorise the use of psychedelics into the heart of capitalism—with some of our leading thinkers and highly capable people—we can actually transform that capitalism into something new. And then, along the way, we can meet the most complex challenges that are being thrown at us like climate change and the complexity of the world we have built. This vision is core to the Center for MINDS’ mission.”

“If we can accomplish all of that, we’ll prove to society that there are other merits and values to this work and this practice, and we’ll push the regulatory bodies toward legalisation from many different angles.”

“Rick Doblin has told us the FDA is open to non-therapeutic applications, that it could also support studies with well persons for life benefits. Perhaps this could be added to the FDA imprimatur and also transform it into an agency that serves us all a bit better.”

“We’re leaving all this genius on the table—or under the table. And it isn’t necessarily that psychedelics are the only tools we can use to unlock it, but it’s the broader focus on cultivating and nurturing that next generation coming up who carry these capacities. If we lose them, we lose access to possibly very positive futures.”

Gathering the data, landing the practice

The Center for MINDS is conducting an informal global survey to investigate how professionals have used psychedelics and other consciousness practices to enhance creativity or problem solving.

“One of the things we could really use are people’s stories—their testimonials—if they’re willing to share,” Damer said. “We invite people who have developed a practice for their own insights to share their protocols, what they do, and whether it involves psychedelics or just meditation on strong English Breakfast tea.”

“Share your entire beautiful cocktail of things that you mix up to prime, garner insight, record it and land it into the world. If you’re a technically creative person, what works for you? And if psychedelics are in the picture, fine. If they’re not, that’s fine too.”

“What we can then do is take these testimonials to donors,” he continued. “Donors might be inspired enough to support both outreach and research programs. Like MAPS, with grounded protocols and best practices, we can eventually approach regulatory authorities to normalise these practices into safe, legal containers which drive beneficial innovation and more mindful leadership.”

“If you have practices and stories around catalysing creativity and your personal set, setting and, as we add, setup, we’d love to hear from you through our site at centerforminds.org,” Damer said.

“You can also propose your own research. You could be a clinical neuroscientist, but you could also be a leader of retreats. MINDS realises that much of the early data is going to come through citizen science, in this case from individual practices and from the many group sessions that are being carried out every day around the world.”

“We also invite you to consider joining MINDS to help us open this next frontier, the fourth path in psychedelic research and practice.”