In her first Dispatch, Dr. Alaina Jaster covered the inaugural Neurobiology of Psychedelics Gordon Research Conference’s Keynote Sessio,n plus the first day of the gathering. Here, she covers the remainder: days 2, 3, and 4.

Editor’s note: GRC has a strict publication policy; thus, the presenters referenced here provided consent for publication. Some of the speakers either did not consent or were not available to provide consent, and therefore were not included. As such, this is not an exhaustive recount of presentations.

***

Words by Alaina Jaster, PhD, for Psychedelic Alpha.

Day 2

Morning: Psychedelic-Evoked Neural Plasticity

The excitement continued on the second full day with a conversation related to neuroplasticity and psychotherapeutic effects, and whether the serotonin 2A receptor is required, moderated by Dr. Katherine Nautiyal (Dartmouth College, United States).

One of these talks focused on a drug outside of the typical discussion: 2-Bromo-LSD. Dr. Argel Aguilar Valles (Carleton University, Canada) shared his work assessing the molecular basis of the behavioural effects of this unique compound. After determining that 2-Bromo-LSD increases spine growth 24 hours post-treatment, they aimed to understand why these changes happen and if this compound shares similarities with LSD.

For this analysis, Valles used bulk RNA sequencing methods, which allow scientists to characterise genetic sequences related to drug effect in specific brain regions, such as the frontal cortex. These experiments compared 2-Bromo-LSD with a variety of psychedelics and yielded interesting correlative results and differential sex effects.

Dr. Linda Simmler (University of Basel, Switzerland) followed with a talk on her work focused on synaptic plasticity in mice following a single dose of psilocybin. A portion of her talk was dedicated to whether or not the commonly used preclinical assay, head twitch response, is really a readout of psychedelic activity in rodents. Sharing data on HTR and metabolism, Simmler encouraged the field to think about the true meaning of head twitching.

The rest of her talk focused on her work with functional plasticity, where instead of just looking at structural changes in neurons, her lab also manipulates and measures signalling from neurons in the prefrontal cortex following psilocybin treatment. Her main interest specific to this project is how modification of excitatory glutamate receptors influences plasticity.

Sticking with circuitry and signalling associated with plasticity, Dr. Yevgenia Kozorovitskiy (Northwestern University, United States) discussed another neurotransmitter system that may play a role in neuroplasticity. Given the role of dopamine in motivational behaviour and reward valence, her lab is interested in learning how dopamine neuron activity is restructured by experiences and ketamine exposure.

Using a model of aversive learning, Kozorovitskiy is able to assess how an animal learns to escape a negative stimulus and how ketamine administration can either help increase escapes or produce more failed escapes. Observing this behaviour, combined with novel tools to assess plasticity, she plans to develop a more translational method to understand why psychedelics—and other drugs—can help individuals who may experience different behavioural outcomes.

The next to present was Dr. Rosemary Bagot (McGill University, Canada), whose primary interests are understanding medial prefrontal cell-type specific impacts of psilocybin administration as it relates to mechanisms of emotion. Using single-cell sequencing techniques, the lab was able to identify highly specific cell types and related gene expression that may explain some of psilocybin’s unique effects.

The literature has extensively reported the relevance of pyramidal neurons in layers five and six of the prefrontal cortex in the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics, but little is known about what areas and neurons are exactly relevant for therapeutic effects and plasticity. To this end, Bagot showed some unpublished findings utilising sophisticated techniques that may shed light on specific receptor pathways.

The last, but certainly not least, of the presentations for this section was Dr. Jessica Walsh (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United States). Dr. Walsh has recently begun researching the utility of MDMA to potentially restore autism-related social deficits in rodent models, assessing juvenile interactions, social memory, and sociability.

Her previously published work identified the role of serotonin in the nucleus accumbens circuit, which has been implicated in motivation and reinforcing properties of social interactions. As an extension of this, she began working with MDMA to identify whether its ability to alter neurotransmitter release, including dopamine and serotonin, could promote prosocial behaviours or rescue social deficits.

Afternoon: Psychedelics and Animal Cognition

The second session was also highly focused on animal models, with the evening session specific to cognitive effects related to psychedelic action, moderated by Dr. Claire Foldi (Monash University, Australia).

One of the presentations came from PhD student Ratna Mahathi Vuruputuri (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, India), who spoke about recently published findings on the acute anxiolytic effects of DOI in rodent models. This paper focused largely on anxiety-related behaviours and which circuit is engaged following DOI administration using a variety of sophisticated methods. Vuruputuri discussed the continuation of these findings in her own work, which includes assessing locomotion and prepulse inhibition of startle response across strains and species of mice and rats.

Dr. Katherine Nautiyal (Dartmouth College, United States) brought a new perspective to psychedelic action with a large focus on activation of serotonin 1B receptors, which, unlike serotonin 2 receptors, are inhibitory. The presentation focused largely on a recent preprint that demonstrated the serotonin 1B receptor is necessary for a variety of psychedelics’ effects in rodent behaviours.

Their recent preprint showed that following psilocybin administration, there were differences in the patterns of c-Fos, a gene related to brain activation, across regions involved in emotional processing and cognitive function. Using genetic manipulations, they were able to demonstrate that serotonin 1B receptors were not involved in head twitch response and that the persisting effects of psilocybin on anxiety-like behaviours and anhedonia are mediated by these receptors.

The last presentation in this series was Dr. Adam Kepecs (Washington University in St Louis, United States), who discussed a lesser-known model for assessing hallucinations across species. Using something called time warping, where mice and humans are trained to respond to auditory signals, he is able to measure decision confidence related to time investment. Kepecs shared data surrounding how administration of various psychedelics alters signal choices and hallucination-like perceptions.

Day 3

Morning: Structure and Function-Guided Drug Discovery

This session was chaired by Sophie Holmes (Yale University, United States) and focused largely on drug discovery, molecular pharmacology and considerations for repeated psychedelic administration.

Dr. Daniel Wacker (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States) shared their continued research into structural pharmacology and the therapeutic potential of 5-methoxytryptamines. He began by stressing the importance of using more than just binding data to understand the role of various receptors in psychedelic pharmacology and that functional measures can reveal more information.

The main question Wacker asked is what determines whether psychedelics prefer one receptor over another. Using structural modelling, like cryo-EM, they are able to solve structures of various receptors with psychedelics bound to them. This allows them to determine the specific amino acids and configurations that implicate various compounds in both affinity and function.

Dr. John McCorvy (Medical College of Wisconsin, United States) continued the discussion of functional assays in drug discovery with a focus on the “next-generation of psychedelics.” He began his talk by highlighting how the field has focused on the serotonin 2A receptors, noting that there are so many other serotonin receptors that we still don’t understand.

One question McCorvy raised is if serotonin 2A receptor activation mediates both subjective and neuroplastic effects—which we know to be true from human and basic science—what are these other receptors up to? His seminar focused on answering this question by presenting unpublished data surrounding profiles of signalling parameters of various receptors and both psychedelic and non-psychedelic compounds. He concluded that this work is not only important for translational applications, but we also may need a new reference compound due to the recent Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) decision to place DOI in Schedule I.

Dr. Devin Effinger (University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, United States) presented his insights into the potential cardiovascular risk of repeated psychedelic ingestion, such as in the practice of microdosing. There have been instances of serotonergic drugs, such as fenfluramine, causing valvular heart disease due to their agonism at the serotonin 2B receptor. Given psychedelics’ activation of these receptors, he partnered with cardiovascular researchers to assess whether repeated LSD would produce similar effects.

Using the most aggressive Fadiman protocol for microdosing LSD adapted for mice, Effinger assessed ventricular hypertrophy via left ventricle diameter, posterior wall diameter, and ventricular volume. LSD did not produce alterations in any of these measures, nor was aortic valve function altered. These studies are just the beginning in understanding psychedelics’ effects on cardiovascular function.

The final presentation of this section was PhD student Aurelija Ippolito (University of Oxford, United Kingdom), who discussed their dissertation work, which focuses on receptor-biased signalling and psychedelic drug action in rodent models. Her studies have used a variety of mechanisms, including binding, functional and genetic measures related to behaviour, and plasticity. Assessing a variety of psychedelics such as DOI, LSD and psilocybin in conjunction with pharmacological and genetic manipulations, Ippolito was able to determine these drugs are all quite different in their biased signalling.

Afternoon: Techniques to Study Drug Action

This session crossed the boundaries of clinical and preclinical research, with a variety of presentations that shared some cutting-edge techniques to understand psychedelic action. It was led by Dr. Robert Malenka (Stanford University School of Medicine, United States).

The first presentation was from Dr. Gitte Moos Knudsen (Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet, Denmark), who discussed her work using PET tracers to understand the molecular, haemodynamic and perceptual effects of serotonin 2A receptor agonists. She shared unpublished data regarding cerebral 2A receptor occupancy and its associations with subjective effects, plasma drug concentrations and functional connectivity.

Knudsen also discussed the importance of setting during a psychedelic experience. Many psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) sessions are held in a certain environment to enhance comfort around the experience, whereas functional studies of psychedelics using brain scanning can be quite uncomfortable. The lab is trying to understand how being in this confined and often loud environment can alter the persistent effects of psychedelics.

The next presentation was from PhD student Daniela Domingues (Paris Brain Institute, France), who had an exciting presentation related to whole-brain mapping and behavioural assessments of a variety of LSD doses. She looked at seven doses of LSD in acute behavioural measures like head twitch response, locomotion and open field tests, followed by light sheet microscopy to view brain activity.

Many were excited about her multi-level analysis of anxiety-like behaviour, where she transformed the position of the mice in the open field to an occupancy map showing how much time is spent relative to the corners, centre or middle walls of the cage. The latter end of Domingues’ presentation focused largely on her data on brain activity, where she identified seven brain regions of interest where LSD is able to up- or down-regulate c-Fos depending on the dose. This could suggest a threshold or sweet spot related to dosing, depending on the specific indication.

In a different vein, Dr. Takashi Kawashima (Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel) discussed psychedelics, stress and neuroplasticity in zebrafish. Interestingly, these fish share about 70% of their genes with humans. Kawashima was interested in how subcortical brain regions contribute to the effects of psychedelics. Using a cold stress test, where the fish are pretreated with psilocybin and exposed to a cold bath, they are able to assess psilocybin’s ability to restore normal (or unstressed) behaviour. After this, they are able to do whole brain imaging to find individual neuronal activity, segmentation, and changes in activity levels, where they identified the habenula as a region of interest.

The final presentation of this session was by Dr. Omar Ahmed (University of Michigan, United States), who talked about a newly engineered mouse line that allows for the assessment of neuroplasticity related to Alzheimer’s Disease. He engaged the audience by asking them to recall various locations on the GRC campus before sharing experiences of people with diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and glioblastoma.

Ahmed’s seminar largely focused on identifying specific cell types in the retrospinal cortex, which is necessary for spatial orientation. His work has found a type of cell called a “low rheobase neuron,” which means it requires a relatively small amount of electrical current to trigger signalling as compared to other neurons. They also discovered a lack of serotonin 2A receptors in this brain region but a large amount of serotonin 2C receptors, and are now aiming to understand how this signalling is taking place using their CRISPR-engineered mice.

Day 4

Morning: Human Psychopharmacology and Therapeutics

The final day of the conference shifted to clinical studies focused on psychedelic pharmacology and therapeutics and was moderated by Leah Mayo (University of Calgary, Canada).

To begin this session, Dr. David Erritzoe (Imperial College London, United Kingdom), who requested to be introduced as “David who does science”, aimed to broaden the conversation surrounding the discrepancy between clinician- and patient-desired outcomes in depression treatment. Analyses have suggested that clinicians focus on symptom management, whereas patients want to prioritise improvements in quality of life.

Given these considerations, much of Erritzoe’s work aims to understand how brain modularity and connectivity influence clinical improvements related to PAT. Ongoing studies include assessing brain mechanisms of psychedelics using PET imaging, clinical trials with psychedelics for chronic pain, anorexia nervosa, and addiction. They most recently published their findings on single-dose psilocybin in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Dr. Carolyn Rodriguez (Stanford University School of Medicine, United States) continued on the topic of OCD, discussing translational therapeutic targets and interventions using ketamine and MDMA. Rodriguez began her seminar by sharing how OCD has a symptom hierarchy and “is more than contamination and handwashing,” suggesting that this symptom variety makes it difficult to treat. Her research aims to use translational therapeutics and novel compounds to help reduce compulsive behaviours.

Animal and human studies suggest ketamine is able to reduce behaviours and OCD symptoms. Rodriguez is now working to replicate those studies with a double blind placebo-controlled study with ketamine compared to midazolam in those with moderate to severe OCD. Another ongoing study in her lab is attempting to identify the mechanism behind the therapeutic outcome, which she thinks may be related to ketamine’s activity at opioid receptors.

The next talk was from Master’s student Danielle Bukovsky (University of Toronto; CAMH, Canada), who is leading a study assessing psilocybin’s safety and feasibility in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI). Her work assesses synaptic loss and reduced synaptic density linked to cognitive decline in older patients using PET and neuropsychological measures of memory and executive function. One major takeaway is that there were no serious adverse events or any adverse events that would be worrisome for older populations.

Matthias Liechti (University Hospital Basel, Switzerland) gave the next presentation on drug interactions and dosing implications for the real-world application of psychedelics. To begin, he discussed drugs that can be used to reverse subjective experiences, including the use of ketanserin for shortening trips or as rescue medication during PAT.

Most interestingly, Liechti described recommendations for dosing and drug interactions. For example, recent findings suggested antidepressants escitalopram and paroxetine are able to reduce the bad effects but not the positive drug effects of psilocybin or LSD. This could suggest that clinical trials could expand inclusion criteria by possibly allowing participants who take SSRIs without discontinuation of the medication.

Next up was Dr. Fred Barrett (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, United States), who discussed networks related to cognitive flexibility and how understanding these may help in addressing stress and distress related to psychedelic outcomes. The frontoparietal network has been shown to predict working memory performance and be involved in cognitive flexibility, with different nodes of this network having specific implications in cognitive control domains. Barrett’s ongoing research is probing whether psychedelics acutely impair cognitive control and memory constructs and how the claustrum, a smaller brain region related to consciousness, is affected. While preclinical studies on this region are promising, he said it’s time to find out “how the humans are humaning.”

The last seminar of this session was by Dr. Jennifer Mitchell (University of California, San Francisco, United States), who spoke about LSD as a potential therapeutic for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). This disorder is commonly misdiagnosed as PTSD and there is often a comorbidity that potentiates symptoms and makes them difficult to disentangle in treatment. Mitchell currently has two ongoing studies, one of which is sponsored by MindMed, testing LSD tartrate for GAD. This study is showing promising results with 100 μg of LSD and tests continued response and remission through 12 weeks.

Another aspect of her work is delineating the role of set and setting in PAT, which is something that hasn’t been empirically tested yet. Mitchell’s study employs a two-by-two factorial design, where she can directly compare interactions between the psychedelic and the setting. Unlike other PAT trials, the work from Mitchell’s lab does not use psychotherapy but rather emotional support to help ground participants in the now instead of pathologising their experiences. She hopes that they can figure out the best container for psychedelic drug intervention and what level of support is truly needed.

Afternoon: Consciousness, Sleep, and Altered Brain States

The final session of the Psychedelic GRC was perhaps the most engaging. It began with an invitation from discussion leader Irene Rembado (Allen Institute, United States) to “enter a different space, not only for our intellect but for our whole selves.” She encouraged the crowd to stand up and participate in a movement exercise to shake out our bodies and our judgements and, “just for tonight, instead of thinking about, we can feel it all together.”

Following the group stretch—or maybe it could be classified as a dance—Dr. Natalie Gukasyan (Columbia/NYSPI, United States) took the stage to discuss her ongoing research on Hallucinogen Persisting Perceptual Disorder (HPPD) in a sample of over 1,000 people. She remarked that psychedelic use is rising, joking that we “changed our minds back in 2019.” But, with this rise in psychedelic use, there is also more risk associated with HPPD, which is incredibly understudied.

Gukasyan shared the growing dataset surrounding self-reported experiences with HPPD symptoms, existing mental health conditions, precipitating factors, clinical presentation and self-medication of symptoms. LSD was the most reported psychedelic to precipitate HPPD symptoms, and people largely reported visual symptoms and depersonalization, the latter not being included in the DSM-5 criteria for the disorder. Lastly, she discussed the treatment techniques that people were using and found many reported antidepressants worsened symptoms, while benzodiazepines were mostly reported to be helpful. Other interventions like yoga, mindfulness and cognitive behavioural therapy were also reported as helpful. If you have experienced symptoms, the study is still ongoing and can be found here.

The next talk was from Dr. Matthew Banks (University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, United States), who discussed his work on understanding the role of plasticity, memory, and awareness of experiences in the long-term effects of psychedelics. He described the findings of his study, published last year, where they used midazolam, a benzodiazepine that produces amnesia, to block memory of the psilocybin experience. They showed that midazolam dose and memory impairment were negatively associated with insight and well-being induced by psilocybin, suggesting a role for memory in the therapeutically relevant effects of psilocybin.

Banks announced they have begun a follow-up clinical trial, RECAP2, which will compare different doses of psilocybin combined with midazolam or placebo to assess plasticity and emotional wellbeing.

Dr. Amy Kuceyeski (Weill Cornell Medicine, United States) presented a computational theory called the “Network Control Theory” as a way to model shifting brain dynamics following psychedelic administration. This theory essentially suggests an interconnected system (the brain) has various parts that have connections between them (circuits) and different states that can be achieved, including cognitive control.

Kuceyeski has been using computational modelling on MRI data from various groups to understand how brain state transition energy can explain psychedelic action. The hypothesis is that the acute effects of psychedelics will decrease the transition of energy and flatten the landscape. Published data from the lab does suggest energy reduction by LSD correlates with more dynamic brain activity across individuals.

Dr. Boris Heifets (Stanford University School of Medicine, United States) delivered the final presentation of the conference. His seminar brought the GRC full circle with a discussion about the replicability study discussed on day one and throughout the conference. He shared what factors make up “the dream” of a translational model, highlighting that his list is far from the reality of the matter, and the paper was a way to determine a common language to make predictions. If models don’t work, “we can move on and get new ones”, he added. He shared some of the details of this collaborative effort, highlighting that it’s just a start and not a verdict.

The second part of his talk was about removing the trip from the psychedelic experience to assess whether the subjective experience is driving positive outcomes. They began assessing this with ketamine in 2023 (see Lii et al., 2023) where they found patients under anaesthesia while receiving ketamine or placebo for depression could not properly identify their treatment group. Interestingly, both of the groups had positive outcomes, which opened the door to further investigation. Currently, Heifets is aiming to test this with psilocybin and is working to determine the optimal dose, EEG marker to predict psilocin effects, and how long the time course of psilocybin is while under anaesthesia.

Conclusions

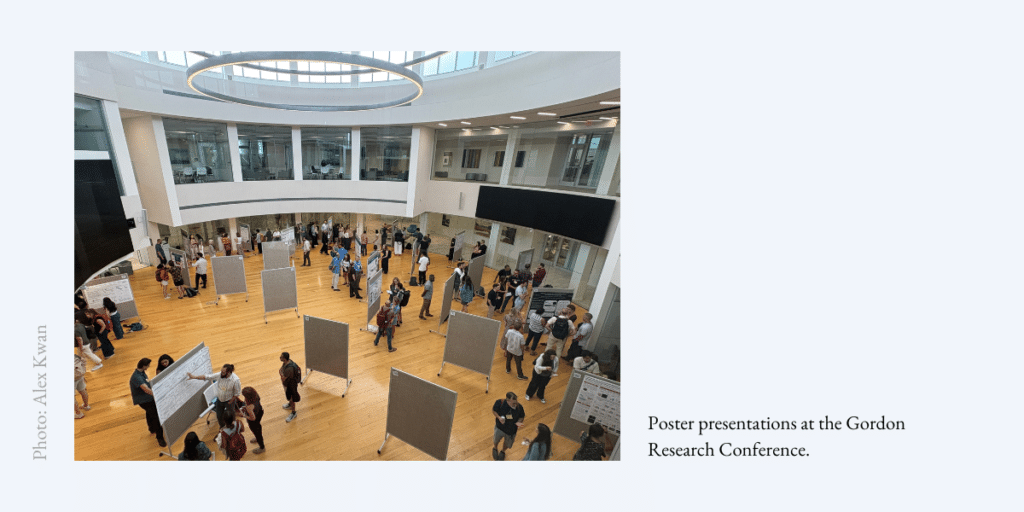

The Psychedelic GRC was quite different from other recent conferences like Psychedelic Science, which took place in Colorado just a month earlier. It was small, single-track, and highly focused on empirical science.

Being in its inaugural year, the psychedelic GRC didn’t have some programming that other GRCs have, like more planned social events, workshops and something called the “Gordon Research Seminar”, which is a trainee-led seminar event that happens before the conference. In spite of this, two young leaders in the field, Dr. Lindsay Cameron (Stanford University, United States) and Dr. Praachi Tiwari (Johns Hopkins University, United States), planned an event that embodied the spirit of the research seminar, bringing students, postdocs and others together.

The GRC had a packed program with several opportunities to learn and interact with one another. The content of the conference was mostly basic science and preclinical, which really demonstrated how many people were doing similar work and why bringing everyone in the same room is so important for innovation.

A major takeaway: the field needs better avenues for communication and collaborative science. A lot of conversation around definitions, best practices, and the value of animal models took place, which led many to think about how scientists of all disciplines can work collectively to understand each other and have a say in how the field moves forward.

When asked about their favourite part of the week, many said it was attending talks that they normally wouldn’t and gaining new insights and perspectives into their own work. A close second was the sense of community and excitement that was felt throughout the week.

Hopefully, the positive reviews from attendees will allow the Psychedelic GRC to continue and become one of the permanent GRCs. If the Psychedelic GRC continues, it will be held in Maine in 2027.

Alaina’s dispatch from the Keynote sessions and Day 1 was published last week, for Pα+ subscribers: