As psychedelics become more visible and accessible in diverse contexts, conversation is shifting from whether they will go mainstream to how that mainstreaming unfolds, and what guardrails are needed to support safety and equity.

Here, Missi Wooldridge, Heather Kuiper, Doris Payer, and Logina Mostafa argue that public health has been largely missing from this rapidly evolving landscape, and that 2025 marked an inflection point for “psychedelic public health” as an emerging field.

Policy is shifting rapidly around the globe, while media coverage, gray‑market dispensaries, religious groups, ceremonial retreats, and ketamine clinics have made psychedelics far more visible and accessible to the general public. The mainstreaming of psychedelics is no longer a hypothetical future. And of course—as sacred medicines, sacraments, and plant teachers, these “soul-mind manifesting” substances have been in relation with humans for much, much longer. By the end of 2025, it became impossible to assert psychedelics are reserved for clinical settings.

The majority of psychedelic use occurs outside formal clinical settings with tightly controlled protocols, instead occurring across a spectrum of contexts and intentions. In ceremonies and churches, at festivals and in informal settings and underground circles, psychedelic use has grown rapidly, resulting in outcomes that range from meaningful and transformative experiences to preventable harms and exploitation. This real-world use far outpaces the development of guardrails such as access and insurance coverage, public education, harm-reduction services, or integration support programs.

Yet a critical discipline has been largely absent: public health. The field designed to promote wellness, prevent harm, and ensure equity at community and population scales has had almost no coordinated presence in psychedelic science, policy, or practice.

The gap: Psychedelics without public health

A 2024 study, Psychedelic Public Health: State of the field and implications for equity, in Social Science & Medicine quantified this absence (Kuiper et al., 2024). Researchers examined 228 accredited U.S. Schools and Programs of Public Health and 59 psychedelic research centers and found that fewer than 10% of public health schools engaged with psychedelics—only 2.6% substantially. Just 10% of psychedelic research centers (PRCs) reported partnerships with public health institutions, and fewer than 3% of PRC personnel held public health degrees.

Structural inequity also surfaced: 92% of PRCs were led or co‑led by people characterized as White-European, 88% as men, and only one center included Indigenous leadership. Fewer than half of institutions visibly addressed social determinants of health, and only about one-quarter addressed Indigeneity.

Taken together, these findings reveal more than a disciplinary blind spot. They describe a structural risk: a rapidly expanding ecosystem of psychedelic use, investment, and policy change with minimal input from the discipline charged with addressing population-level safety, equity, and systems. Integrating public health infrastructure and expertise into the ecosystem is essential because, where that integration is missing, we risk, for example:

- Rising awareness and access without corresponding, evidence-informed public education or widespread harm reduction initiatives

- Policy debates dominated by clinical, commercial, or carceral frames, rather than prevention, promotion, and community wellbeing

- Fragmented, clinic-centered models unable to absorb demand, leaving most people who use psychedelics outside formal care

- Health and social support systems—from emergency departments to family services—unprepared to respond to psychedelic‑related crises or opportunities

- Missed opportunities to mobilize psychedelic benefits toward population-level healing

Meanwhile, communities most harmed by the War on Drugs, and Indigenous peoples whose ceremonial practices have profoundly shaped contemporary psychedelic protocols, continue to experience disproportionate burdens and insufficient benefits.

In short, the field is missing the very infrastructure designed to translate individual therapeutic promise into collective wellness.

From community to clinic: What public health brings—and why it matters

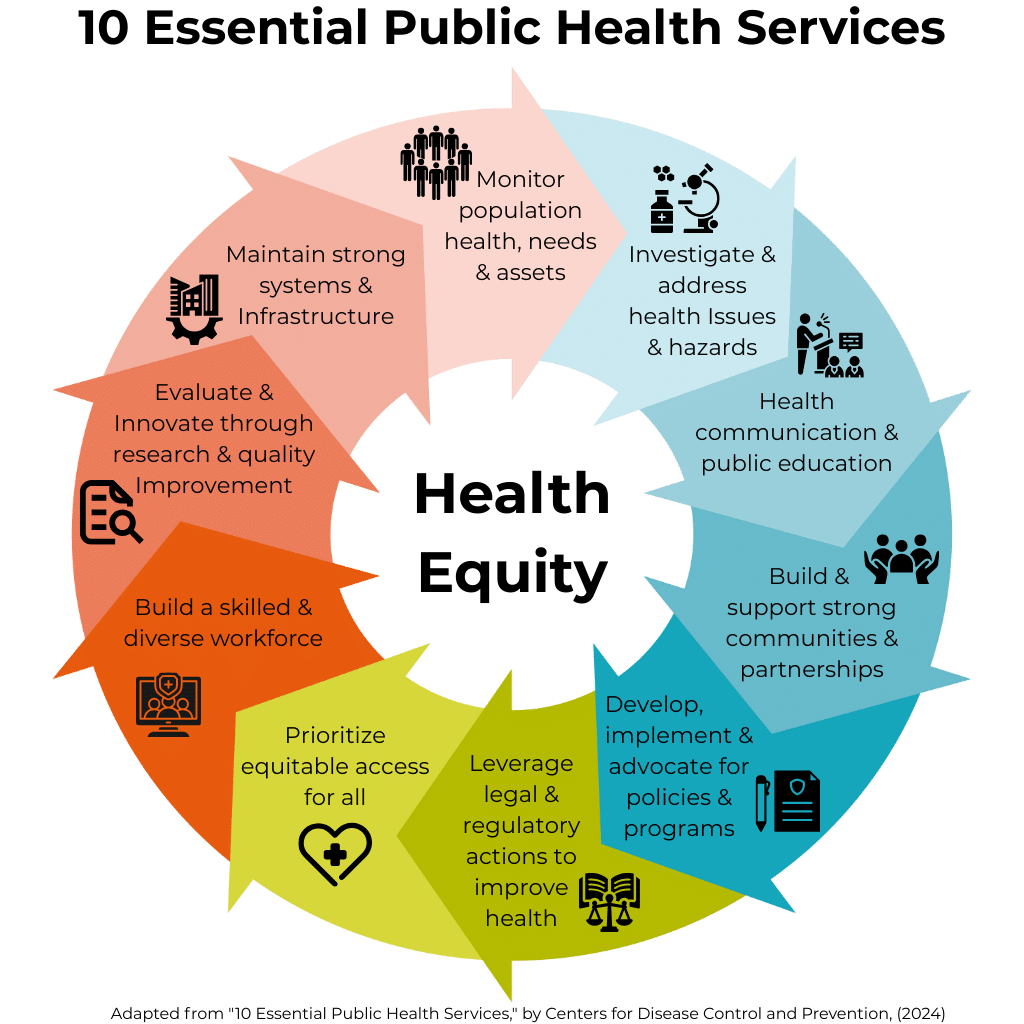

Public health is an interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral field that aims to promote and protect the health of all people and the communities in which they live, learn, work, and play. Unlike biomedical models focused on individual clinical outcomes, public health centers communities, addresses social and structural determinants, and designs systems to address health needs regardless of the regulatory status of a substance or behavior.

Several core disciplines and tools are directly relevant to psychedelics:

Health Equity is foundational to public health practice. It requires addressing social determinants: income, education, housing, discrimination, historical trauma, and prioritizing those most harmed and least served. For psychedelics, this means confronting the communities most impacted by the War on Drugs and Indigenous peoples whose knowledge systems underpin contemporary psychedelic medicine yet have been excluded from research leadership, policy design, and equitable access.

Evidence-based theories, models, and frameworks are the road map for nearly everything in public health. For example, the Socioecological Model of Health helps us see that outcomes are shaped not only by individual mindset, but also by relationships, communities, and policy environments—so “set and setting” can naturally expand to include housing, norms, and laws. Social Cognitive Theory explains how people learn from others and build confidence to change, which can strengthen how we support people to prepare for, navigate, and integrate psychedelic experiences. The Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model views change as a process rather than a single decision, mirroring how people move from curiosity to use, to integration—or stepping back. Building on these, the Spectrum of Use framework views use along a continuum—from beneficial to risky to problematic—so the field can match responses (education, harm reduction, early intervention, or care) to where people actually are, without needing to reinvent the wheel.

Community health centers where people live, work, learn, and play, working in partnership with communities rather than designing interventions from the top down. Community health workers, peer educators, harm reduction specialists, and public health nurses are examples of the public health workforce on the ground, trusted by and often part of the populations they serve. Public health recognizes and builds on this foundation, elevating community expertise and ensuring that interventions are culturally grounded, trauma-informed, and responsive to local needs and values.

Epidemiology, surveillance, biostatistics, and data science analyze population-level data, estimate incidence and prevalence, identify disparities, track patterns of health and disease to identify risk factors and trends and model policy scenarios. For psychedelics, this means monitoring prevalence, demographics, adverse events, and beneficial outcomes at population scales through poison center data, emergency department surveillance, and community-based surveys. A recent U.S. poison center analysis showed a threefold increase in psilocybin-related encounters from 2013 to 2022, with the steepest rise starting in 2019 (Montoy et al., 2025)—exactly the signal epidemiologic surveillance is designed to catch and contextualize.

Health program, policy, development, implementation, and evaluation translate evidence into practice by designing policies and programs, supporting their implementation, and rigorously assessing their impact—from drafting health department guidance and licensing standards to building workforce training and service delivery models. Implementation and evaluation science specifically bridge the gap between theory and real‑world practice, providing frameworks to scale up what works, adapt it to diverse settings, and monitor for unintended consequences.

Health promotion and disease prevention focus on creating conditions that keep people well and intervening early, across levels of prevention—primary (preventing problems before they start), secondary (early detection and risk mitigation), and tertiary (reducing the impact of established conditions). Applied to psychedelics, this lens moves us beyond seeing them only as treatments for illness towards, where appropriate, integrating them into broader strategies that support mental, relational, and community wellbeing before crises emerge.

School-based and public education reach young people with accurate, developmentally appropriate, non-stigmatizing information. Safety First: Real Drug Education for Teens, the nation’s first harm reduction-based drug education curriculum, showed significant results: students who completed Safety First had increased harm reduction knowledge, were less likely to use substances, and were less likely to use at harmful levels. The curriculum teaches critical thinking to evaluate drug information, decision-making strategies, and advocacy for health-oriented policies—moving beyond abstinence-only messaging that alienates youth.

More recently, the Before You Trip pilot campaign targeted Gen Z in Colorado with psychedelic safety education using social media, influencers, and harm reduction messaging, which yielded significant increases in both awareness and knowledge of risk factors and harm reduction strategies.

The legacy: Who built psychedelic public health before it had a name

The idea of a public health approach to psychedelics did not emerge in 2025 or in academic centers. Indigenous communities have holistically stewarded sacred medicines, despite criminalization. Their perseverance has carried forward ceremonial practices and knowledge systems that are grounded in relationship and committed to collective care and healing.

Harm reduction pioneers in nightlife and festival settings, such as DanceSafe chapters establishing a safety net and providing drug checking and peer education since the 1990s; the Zendo Project offering trauma‑informed, compassionate peer support for people in psychedelic distress; the Global Psychedelic Society, which has grown from early organizing in San Francisco into a network of more than 200 societies worldwide that create spaces where people who use psychedelics can gather, feel safe and supported, and access education; the Brooklyn Psychedelic Society, advancing this community‑based approach through its Trellis integration and support program; and countless mutual aid networks, queer and BIPOC organizers, and underground therapists—built community‑based care when formal systems failed to serve people whose use fell outside medical channels.

Nearly a decade ago, Haden, Emerson, and Tupper (2016) proposed a public health vision for psychedelic regulation emphasizing harm reduction and social determinants. In 2023–2024, the Canadian Public Health Association convened a national forum and published a position paper calling for population-level strategies and equity-centered policy (CPHA, 2024).

Major U.S. agencies explored the terrain. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) hosted a workshop on psychedelics as therapeutics, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) explored mainstreaming implications for behavioral health, and the American Public Health Association (APHA) curated scientific panels on psychedelics at their Annual Meetings in 2025 (and their first-ever in 2024) , which centered on the need for a coordinated public health response.

These efforts made three things clear. First, any attempt to formalize psychedelic public health must stay accountable to its roots—honoring and resourcing the communities and practitioners who have carried this work, rather than repeating patterns of extraction and exclusion. Second, public health tools such as surveillance, health promotion, harm reduction, systems design, and evaluation are directly relevant to psychedelics. And, third, until now, there has been no dedicated home to bring these tools together into a coherent discipline or to support practitioners, communities, and policymakers who are already being asked to respond.

The 2025 Convergence

The Social Science & Medicine study highlighted the gap produced by the absence of public health in psychedelic leadership and ecosystem and recognized psychedelic public health as a distinct discipline, calling for a coordinated response. In 2025, that call began to be answered. Momentum shifted from isolated projects to coordinated action, new partnerships, policy engagement, and broader uptake of psychedelic public health language and practice. The activation of a new field: Psychedelic Public Health.

Several forces converged in 2025 to move psychedelic public health from aspiration to coordinated action and more are in the works for 2026 and beyond. The New Mexico Medical Psilocybin Act became historic in housing psychedelic policy from the outset in public health infrastructure, in this case in the New Mexico Department of Health’s Center for Medical Cannabis and Psilocybin. Alaska’s proposed Natural Medicine Act prioritizes community wellness and equity, traditional use, and education for the public’s health, and hosted the state’s first psychedelic health policy briefing. The Maryland Task Force on Responsible Use of Natural Psychedelic Substances incorporated a public health framework into its access models, and psychedelic harm reduction pioneers, Zendo Project, incorporated public health behavior change theory into assessment of its programming. At the same time, rising real-world use documented through surveys, poison center data, and community reports, underscored that psychedelics are already a population health issue, whether or not systems are prepared to respond.

The question is no longer whether to move beyond prohibition, but what to move toward—and who decides. Psychedelic public health brings the infrastructure, tools, and mandate to ensure the answer prioritizes equity, safety, community participation, and collective flourishing rather than commercialization and disparity.

Priorities for the field

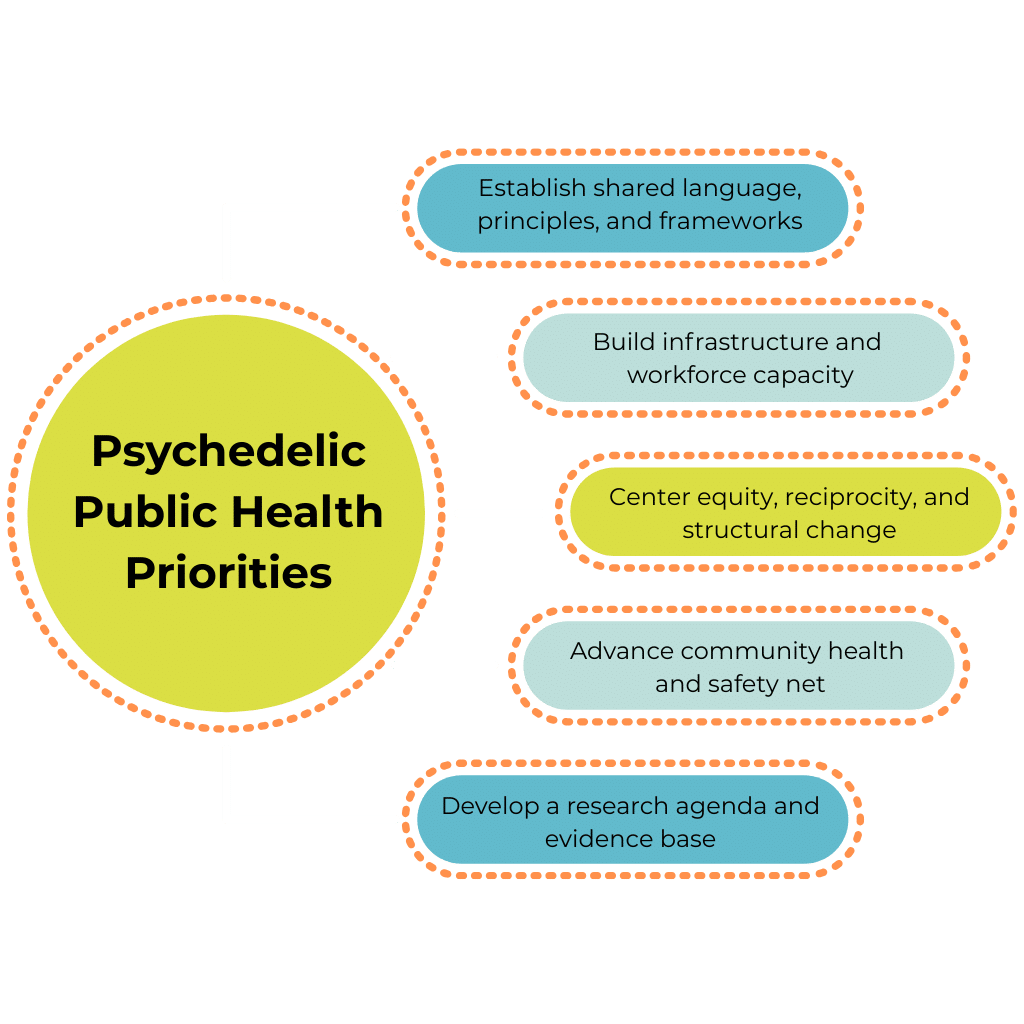

The psychedelic landscape is moving fast and public health must move with intention. The field will not be built by any single organization or initiative—it requires collective effort across communities, institutions, and disciplines. Five foundational priorities have emerged—shown below—that can anchor coordinated action and offer a roadmap for building this field with rigor, equity, and accountability. To guide this work, the Center for Psychedelic Public Health proposes to convene community leaders, Indigenous knowledge holders, and public health practitioners, policy makers, scientists and scholars to collaboratively define shared priorities, language, ethics, and research and action agendas.

From individual treatment to collective healing

As the vehicle to move psychedelics beyond the biomedical, clinical, individual model toward collective impact, public health metrics differ from clinical trial outcomes. These metrics ask not only, “Does this work for this patient?” but “How do we ensure it works equitably, safely, and sustainably for entire communities and populations?”

The convergence that accelerated in 2025 represents the beginning, not the culmination, of psychedelic public health. The work ahead is to build the field with integrity, rigor, and commitment to equity and reciprocity—honoring the communities and knowledge systems that laid the foundation and ensuring public health takes its place as a central pillar of the psychedelic future.

Missi Wooldridge, MPH, Heather Kuiper, DrPH, MPH, Doris Payer, PhD and Logina Mostafa, MPH are affiliated with the Center for Psychedelic Public Health, which says its mission is to “amplify psychedelic benefits for community, population, and planetary health”.