Meet the Panelists

Hailey Gilmore

Since 2020, Hailey has built and overseen the strategy and process for the Investigator-Initiated Trials Program at MAPS Public Benefit Corporation. The nexus of health, justice, and impact is the ethos for the work she chooses. Prior to joining MAPS PBC, Hailey managed NIH-funded HIV clinical trials in the U.S., Latin America, and Africa, for 12 years. She has contributed to the lifecycles of over fifty trials globally spanning the fields of therapeutic psychedelics, HIV, reproductive health, and substance use harm reduction, including multiple trials which led to FDA approvals and the adoption of international clinical practice guidelines.

Hailey would like to add that, "my views are my own as a professional in the space and should not be construed as official opinions on behalf of MAPS PBC.”

Hailey Gilmore

Since 2020, Hailey has built and overseen the strategy and process for the Investigator-Initiated Trials Program at MAPS Public Benefit Corporation. The nexus of health, justice, and impact is the ethos for the work she chooses. Prior to joining MAPS PBC, Hailey managed NIH-funded HIV clinical trials in the U.S., Latin America, and Africa, for 12 years. She has contributed to the lifecycles of over fifty trials globally spanning the fields of therapeutic psychedelics, HIV, reproductive health, and substance use harm reduction, including multiple trials which led to FDA approvals and the adoption of international clinical practice guidelines.

Hailey would like to add that, "my views are my own as a professional in the space and should not be construed as official opinions on behalf of MAPS PBC.”

Balázs Szigeti

After obtaining a physics degree and a PhD in computational neuroscience, Balázs spent a few years as a biomedical software engineer at the Icahn Institute of Genetics in New York. He became involved in psychedelics science in 2016 when he invented 'self-blinding', a novel methodology that enables self-experimenters to implement their own placebo control without clinical supervision. Using this methodology, Balázs led the self-blinding microdose study, one of the largest placebo-controlled studies on psychedelics to date. Balázs is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Imperial College’s Center for Psychedelic Research, where he investigates the intersection of placebo effects and psychedelic medicine using innovative experimental designs and modern data science techniques.

Balázs Szigeti

After obtaining a physics degree and a PhD in computational neuroscience, Balázs spent a few years as a biomedical software engineer at the Icahn Institute of Genetics in New York. He became involved in psychedelics science in 2016 when he invented 'self-blinding', a novel methodology that enables self-experimenters to implement their own placebo control without clinical supervision. Using this methodology, Balázs led the self-blinding microdose study, one of the largest placebo-controlled studies on psychedelics to date. Balázs is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Imperial College’s Center for Psychedelic Research, where he investigates the intersection of placebo effects and psychedelic medicine using innovative experimental designs and modern data science techniques.

Boris Heifets

Boris Heifets is an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine at the Stanford School of Medicine. He has had a lifelong interest in neuroscience and hopes to apply basic neuroscience insights to the practice of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine. His basic and clinical research aims to understand the mechanisms of action for emerging rapid-acting treatments for psychiatric disease, including ketamine, MDMA and psilocybin, and how they might be incorporated into perioperative clinical care to improve patient outcomes.

Boris Heifets

Boris Heifets is an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine at the Stanford School of Medicine. He has had a lifelong interest in neuroscience and hopes to apply basic neuroscience insights to the practice of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine. His basic and clinical research aims to understand the mechanisms of action for emerging rapid-acting treatments for psychiatric disease, including ketamine, MDMA and psilocybin, and how they might be incorporated into perioperative clinical care to improve patient outcomes.

What do you perceive to be one of the most significant methodological challenges in psychedelic trials?

Hailey Gilmore: Blinding and expectancy bias are obvious responses here, so I am going to name a structural challenge that contributes to methodological challenges: the lack of public-private partnership in this sector. Innovation is driven in other disease areas by substantial government support of scientists. Many of us have backgrounds in disease areas – e.g. HIV, oncology – that have benefited from the government grant system. Competitive federal funding helps to ensure access to state-of-the-art methodology and trials with adequate sample sizes to demonstrate irreproachable signal, as well as initiatives to incentivize diverse clinical cohorts. The need to increase and diversify samples in psychedelic trials (which MAPS PBC has had some success) to best meet the RCT gold standard in drug development could be benefited by enhanced federal/state fiscal support. Recent legislation mandating this, as well as agency statements on research priorities, is encouraging, but needs to be more broadly adopted.

Balázs Szigeti: The big question with every trial is whether positive results will transfer to the real world or not. Clinical trials are a highly artificial setting where the sponsor has a number of ways to bias the results. Thus, medications often do worse in real life compared to trials. This question of ‘external validity’ is particularly relevant for psychedelic therapy due to its complexity. Psychedelic treatment is not just about the drug, but rather cooperating with the therapist and with the experience. These components are impossible to standardize, making the question of external validity that much more relevant. I am more intrigued to see the Oregon roll out than the results from any formal trial.

Boris Heifets: It’s still the hype, (and apologies to Michael Pollan for the connotation the “MP effect” may have taken on). The aura around psychedelics—the novelty, the promise, the dire need for better mental health—have a real impact on clinical trial participants. Making it through screening to enroll in a psychedelic study is exciting, and rare. Take that one step further and imagine, after all that effort, the disappointment of being in the placebo group, versus the un-maskable realization that you are most definitely in the “real” arm. It’s like winning the lottery while in the middle of a drug trial. Especially for studies of mood, we may be measuring the effect of winning versus losing, as much as any drug-specific effect. The hoping, the effort, the validation – these can be profoundly therapeutic in their own right…but may have little to do with what’s in the pill.

Can you share one or two psychedelics-related trials that you find intriguing from a methodology standpoint?

Hailey Gilmore: Given my role, I can’t be specific about which trials, but I am encouraged by the use of waitlist-control arms in a number of the study designs that have crossed my desk in the last few years. It’s not without its critiques, of course, but can be an elegant way to introduce some level of comparator and mitigate spontaneous remission, without introducing issues of blinding and raising costs or complexity too much.

Balázs Szigeti: Most published psychedelic trials follow some variation of a standard trial design. To be fair, deviating from established standards is risky as it is hard to know how regulators and the editors of prestigious journals are going to look at it. I experienced some of these difficulties personally when conducting the self-blinding microdose trial, which had an unusual design. That being said, there are some exciting, innovative trials in the pipeline. I am most looking forward to seeing the results when Charles Raison’s team is going to administer psilocybin to sleeping patients1, maybe solving the issue of blinding. Time will tell.

Boris Heifets: One of my favorites – testing the effect of MDMA on the pleasantness of touch, Bershad et al. 2019, from Harriet de Wit’s group. I hope more researchers emulate the study design – they told participants they would receive any one of several drugs, but in reality they tested placebo, two doses of MDMA, and one dose of methamphetamine. Methamphetamine, it turns out, is surprisingly difficult to distinguish from MDMA. That uncertainty allowed them to ask whether simply believing you took MDMA was enough to drive the touch effect – it wasn’t. There is no better way, in my opinion, to show a drug-specific effect than this.

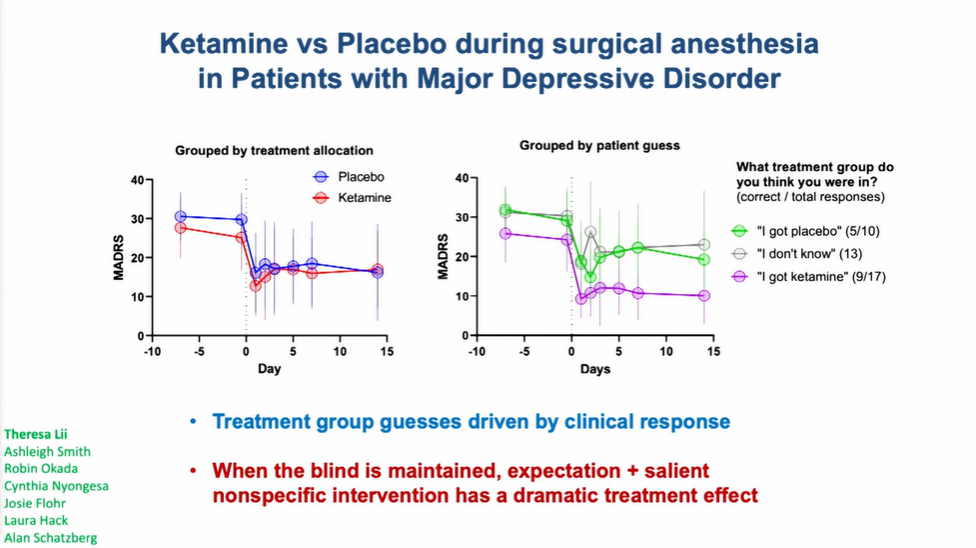

Case study: Boris Heifets’ group has shared preliminary results from a trial that evaluated intraoperative ketamine vs placebo in depressed patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery requiring anaesthesia. What do you think of this trial design, and the preliminary results?

Hailey Gilmore: Bravo to this team for seizing an opportunity! The legal status and safety and effect profiles of ketamine helped to present a very unique set of circumstances for answering an important question about blinding and expectancy bias, and the ability to leverage a placebo effect – which is, in fact, an effect! Sometimes we neglect that it can be powerful when blinding is maintained. This is the kind of creative trial design we love to see, though of course, there will be challenges to replicating with other psychedelic compounds under investigation, and the results seen may not necessarily be widely reproducible in clinical practice.

Balázs Szigeti: It’s a very cool trial and the results are potentially very bad news for ketamine. Intuitively the results suggest that either expectancy explains ketamine’s efficacy or that conscious experience of the ketamine trip is required for greater than placebo efficacy. However, before making any strong conclusion, I would like to see the details in the publication. As I mentioned above, I am very excited to see a similar experiment with a classic serotonergic psychedelic such as psilocybin. Ketamine is an anesthetic, so it works well with this ‘administer while asleep’ approach. Psilocybin is far from an anesthetic, so it’s hard to know what will happen.

Boris Heifets: There are a few interpretations to the data – however, one thing we most definitely did achieve is to drive a placebo effect that could probably get FDA breakthrough status. I’m… half joking. Placebo is an unfortunate catch-all term that includes a set of powerful therapeutic processes engaged, in our case, by hope, passing control to a trusted caregiver, and reveling in surviving a stressful journey. Like any physiological process, placebo has a mechanism – it is probably complex, and it will not surprise me if that mechanism overlaps considerably with that of ketamine and psychedelic therapies.

What other types of professions or groups should be involved as stakeholders in psychedelic trial design?

Hailey Gilmore: More rigorous statistical input earlier in design is a given here. Above I noted how increased public funding, such as in other disease areas, can open doors for access to critical research infrastructure –paying for a statistician’s time, engaging the services of a University clinical research coordinating center, or professional development opportunities for clinicians (often the folks submitting trials) to get training in methods.

Also, I have a public health background, and spent many years working on trials adapting efficacious behavioral and biomedical interventions from the Global North to more resource-constrained settings (Africa, Latin America). As we see the proliferation of psychedelic trials globally, I would encourage the field do more community-based participatory research practice. There are a number of frameworks, such as ADAPT-ITT that exist to adapt interventions to local cultural context that can be deployed, as it is inadvisable to assume the same model will work everywhere.

Balázs Szigeti: Health economists. Right now, we are testing psychedelics coupled with talk therapy as a composite treatment. Psychedelics are cheap, but therapy is expensive. I would bet that in most countries one hour of therapy is more expensive than a handful of LSD blotters. If psychedelic treatment requires talk therapy the way it is practiced in current trials, then the cost of the treatment will be very high; maybe prohibitively high for mass treatment. Maybe shorter acting psychedelics, such as DMT, or group therapy can solve this issue. Involving health economists and thinking about opportunities for cost reduction may help to circumvent this potential scaling problem of psychedelic medicine.

Boris Heifets: The “therapy” part of psychedelic-assisted therapy is still rather underdeveloped. I hope we will see a much wider variety of techniques that will push the boundaries of what’s possible in these altered states – from hypnosis to physical therapy and beyond.

We’re focusing, here, on the methodological challenges pertaining to psychedelic trials. How might these discussions have relevance, and impact, beyond psychedelics?

Hailey Gilmore: Psychiatry/psychology haven’t experienced a pharmaco-revolution in roughly 50 years. It’s been said a silver lining to the global COVID pandemic has been increased attention to mental health, in private and public discourse. This is directly relevant to state actors getting involved to accelerate innovation, increase access to treatments, and better equip (and equip empirically more) professionals to do their jobs. It’s also an opportunity for the field(s) to look at learnings in other disciplines – such as public health – about implementation, access, and intervention targeting. We can discuss increased public investment while also championing creative approaches to leveraging a placebo effect, for example, or streamlined trial designs that aren’t RCTs (with their associated cost, blinding, and complexity issues). Clever statisticians have long bemoaned the challenges of the RCT gold standard and have itemized elegant alternatives. As we shift into a new paradigm for mental health, perhaps other paradigms will also shift.

Balázs Szigeti: Currently the scientific literature assumes that not telling patients whether they received an active drug or placebo is the same as patients not knowing whether they received an active drug or placebo. This assumption is obviously broken with psychedelic drugs, so researchers can no longer pretend that this is the case. Psychedelic trials are often criticized for this lack of blinding, but what is often lost in this discussion is that blinding does not work well with more traditional treatments either. For example, the break blind rate with SSRIs is about 65-70%, which is not as high as with psychedelics (around 95%) but still far from the 50% corresponding to ideal blinding. I think psychedelic research will catalyze the recognition that effective blinding is much more difficult to achieve in practice than previously thought.

Boris Heifets: The basic confounds of expectancy and adequate masking of treatment groups have always been a challenge for clinical trials of psychoactive medications. The randomized placebo controlled trial is not perfect by any means, and psychedelics have really forced the issue about how much expectancy, hope and the ritual of being in a study contribute to the improvements that participants experience. The same difficulties apply for evaluating the efficacy of psychotherapy – we may need to think beyond RCTs.

If attempts at controlling for things like blinding and expectancy ultimately fall short, what next?

Hailey Gilmore: Other disease areas utilize registries of medical information to select matched controls when attempting to evaluate the effect of an intervention in scenarios when an RCT may not be possible, for whatever reason (including ethics, cost, time). The FDA has published a framework for establishing Real World Evidence. The safety of many of these compounds has been assessed through numerous Phase 2 studies – especially ketamine which is already widely available and used. Trials that incorporate hybrid or pragmatic design elements are increasingly possible! All these approaches should use state-of-the-art statistical methods to evaluate causal inference, and reproducibility and open science principles to increase rigor (see Petranker, Anderson, and Farb 2020 for an excellent overview of this).

Balázs Szigeti: Blinding is highly valued in evidence-based medicine, because in theory it distributes expectancy effects equally between treatment arms, effectively canceling out expectancy biases. If blinding is not possible for any reason, there are alternative strategies to achieve the same goal. For example, experimental manipulation of treatment expectations prior to the treatment should be explored. I am currently trying to raise funds for such a trial, fingers crossed. Another alternative that I am currently working on is to use machine learning to estimate the magnitude of the expectancy response based on baseline variables. It’s difficult to say right now how well either of these approaches will work, but I am excited to try!

Boris Heifets: The placebo control rests on the idea that insight into the details of the therapeutic process is “breaking the blind”. Yet, that type of insight sits at the heart of psychedelic therapy, and high-quality therapy more generally. There are of course other trial designs, like comparative efficacy, once we have a collection of psychedelic-class therapeutics that can be tested head-to-head. Maybe we will find a psychedelic that can silently rewire us to be more stress resilient, more open to new experience, more adaptable, and show us that the noise of the trip is just the sound of a billion synapses blooming. Yet, I can’t give up on the idea that we will one day understand how hope and expectation work, not so we can obliterate them in search of a miracle pill but rather to embrace the processes of preparation, immersion, and integration, and fold them into a mature biomedical mental health model.

Visit our Spotlight on Psychedelic Research Methods page for more perspectives on psychedelic research methods.

Part of our Year in Review series

This content is part of our 2022 Year in Review, which looks back at the past year through commentary and analysis, interviews and guest contributions.

Receive New Sections in Your Inbox

To receive future sections of the Review in your inbox, join our newsletter…

- Consciousness, Psilocybin, and Well-Being (CoPE Pilot) (NCT05592379)