Welcome to the second issue of The Psychedelic Practitioner, a new publication for the evolving practice of psychedelic care.

With preparations for the winter festivities in full swing here in London, at Psychedelic Alpha we’ve been focusing on another form of preparation: Psychedelic Preparation.

This theme anchors several featured pieces in today’s edition: insights from Rosalind McAlpine, who has developed and validated a psychedelic preparedness scale; reflections from our network on what preparedness means for practitioners; and, perspectives from Eddie Jacobs and Bryony Insua-Summerhays on the ethics of preparation. As always, you’ll also find our regular programming woven throughout.

Looking ahead, upcoming editions will continue to follow the arc of the conventional psychedelic therapy pathway: next with a focus on Dosing, and then Integration, with content tailored to each stage.

A big thank you to the over 200 readers who completed the survey from our first issue back in October. Your feedback has been invaluable in helping shape future editions and highlighting what matters most to our community.

As a reminder, Issues are currently published every other month. Join our free newsletter to receive them:

Our goal is to make this a worthwhile and practical resource for many of you, so please don’t hesitate to reach out with feedback or content ideas for future Issues.

Josh Hardman and Alice Lineham

The Editors, The Psychedelic Practitioner

Sponsor Message

Psychedelic Alpha is grateful to the folks at Fluence, the first sponsors of The Psychedelic Practitioner.

Begin your journey in psychedelic therapy with Fluence. Introduction to Psychedelic Therapy is a self-paced, CE-granting course trusted by clinicians seeking a grounded overview of the field. Register before January 1st to access our year-end special of 70% off and take your first step toward any of our certificate programs.

Vitals

Vitals is your pulse check on the psychedelic field: a concise scan of the developments, discoveries, and debates that matter most for practitioners. Each item ends with the Bottom Line, for those of you who are pushed for time or want our read on the news.

Ahead of Schedule: Compass Pathways Accelerates Psilocybin Launch Timeline by up to 12 Months

Last month, psilocybin drug developer Compass Pathways announced that it is accelerating its U.S. launch timeline by 9-12 months following a “positive” September meeting with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the completion of enrollment into its second, larger Phase 3 study.

It appears that the FDA is willing to accept a rolling submission of Compass’ new drug application (NDA), which is partially responsible for the more aggressive timeline.

Bottom Line: If all goes to plan, the company’s synthetic psilocybin (COMP360) could be FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression as early as late next year.

Beyond the Trip: Neuroplastogens Show Early Promise as Microdosing Falters

While much of the mid- and late-stage psychedelic drug development pipeline features high-dose candidates that involve potent subjective experiences, some sponsors are exploring low-dose programs or even so-called non-hallucinogenic psychedelics (or, ‘neuroplastogens’).

On the low-dose front, MindBio’s LSD microdosing for MDD program failed entirely in an 89-patient Phase 2b study that missed on all endpoints. While depression scores did go down in the LSD group, those who received the active placebo (caffeine) fared even better.

The topline readout is yet another blow to microdosing. In Bulletin 211, Psychedelic Alpha covered a longitudinal analysis of two psilocybin truffle microdosing RCTs (N=60) that delivered a null finding with respect to effects on cognition and mood. And, in the drug development world, MindBio’s failed program joins MindMed’s: that company’s LSD microdose for ADHD project also flopped at Phase 2 (N=53).

The question of whether neuroplastogens, which aim to eschew the trip, will prove to be therapeutic remains an empirical one, but one company is beginning to generate positive signals in humans. In late October, Delix Therapeutics posted an early efficacy signal from an 18-patient Phase Ib study of its lead candidate, DLX-001, in major depressive disorder (MDD). The drug, zalsupindole, is a non-hallucinogenic analog of 5-MeO-DMT, and the company reported a 12-point drop on the MADRS at day 8 (following either once-daily or twice-weekly administration for one week).

Bottom Line: As microdosing takes another ‘L’ in the clinical trial context (read more in Research Radar, below), so-called non-hallucinogenic psychedelics (‘neuroplastogens’) are beginning to print early efficacy signals as they enter human subjects.

Psychedelics in D.C.: Up to Three Approvals Expected within 18 Months

Psychedelic Alpha Editor Josh Hardman shared a Dispatch from Washington, D.C., that reports substantial tumult not only across the political and regulatory apparatus but also within the psychedelics field itself, which is by no means putting on a concerted front in the U.S. capital. Despite that discord, there does appear to be a quiet confidence among those in the know that multiple FDA approvals of psychedelics are close at hand, with up to three possible in the next 18 months.

While concrete psychedelics-related progress has been elusive, ARPA-H, the U.S. healthcare moonshots funding agency, announced a $100M effort to “demystify” mental health and catalyse rapid-acting behavioural health therapeutics, including psychedelics.

Bottom Line: After many months of excitement from some corners of the psychedelics field, we might be approaching some more concrete concessions or catalysts emerging from D.C. Read more in Going Global, later in this Issue.

Recent Interviews: Subjectivity, the Patient Experience, and… Donuts

Psychedelic Alpha has published two Interviews since our last Issue that cover practitioner-related topics.

In mid-November, we published a discussion with psychiatrist, therapist and researcher Dr. Óscar Soto that covers a broad array of topics and learnings from the coalface of psychedelic research and practice. Soto also calls on his colleagues to focus on the subjective experience, including a patient’s perspective and first-person experience. He thinks that psychedelics offer an opportunity to bring that back into psychiatry.

Speaking to Psychedelic Alpha last month, meanwhile, Compass Pathways’ Chief Patient Officer Steve Levine described the company’s development of synthetic psilocybin delivered alongside psychological support as “making donuts”. It’s up to healthcare providers, he continued, to “put the icing on them and the sprinkles.” That may include pairing them with evidence-based psychotherapies, for example, which Levine thinks could enhance outcomes.

Bottom Line: Keep an eye out for interviews with Samuel T. Wilkinson (published yesterday) and Joost Breeksema, which are full of practitioner-relevant topics.

What is Psychedelic Preparation?

Preparation for a psychedelic experience undertaken in an intentional setting is now widely recognised, across traditional lineages and contemporary clinical trials, as a decisive factor in shaping outcomes. Though no single definition exists, insights can be gleaned from Indigenous practices, clinical trial protocols, harm reduction frameworks, and underground knowledge.

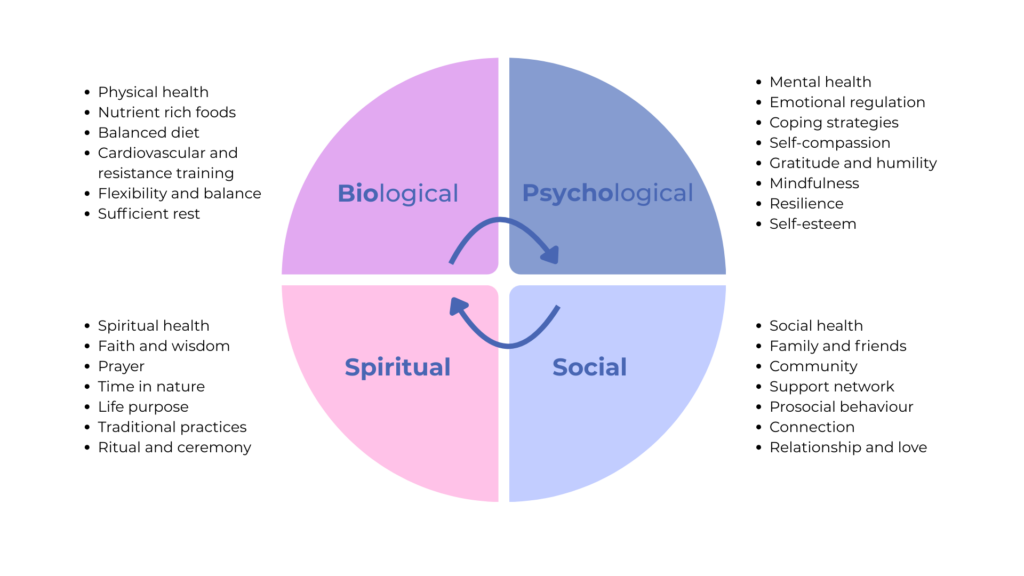

At its essence then, preparation is the process of becoming psychologically, physically, socially, and spiritually ready for both the content and consequences of the experience. It is the first phase in the well-known tripartite model of psychedelic work: Preparation, Dosing, Integration. It marks the beginning of peeling back the layers of the onion so that, by the time dosing arrives, one is ready to surrender to the experience. Preparation is a phase of unknowns: trepidation, anticipation, even thoughts of backing out; but it’s also one of slowing down, cultivating awareness, and reconnecting with body and breath.

While our focus in this Issue is primarily on preparation within clinical contexts, such as trials and clinics, we acknowledge the many other ways preparation is understood and practiced. In many Indigenous traditions, for example, the emphasis is on interpersonal and collective dimensions (such as fostering spiritual alignment, relational healing, and collective wellbeing) rather than focusing solely on the individual. Here, preparation often takes ritual form: dietary protocols, tobacco cleanses, and protective practices serve not only the individual but also the integrity of the group and its wider ecological relations. Western frameworks, by contrast, focus primarily on the intrapersonal: individual psychology, mindset, and personal goals.

Despite differences across contexts, certain shared themes emerge. Safety is often the most immediate concern of preparation. In clinical trials, this may involve psychoeducation, medication washout, and logistics. Navigation, also a key endeavour, aims to familiarise participants with the process and the environment. Building therapeutic trust, cultivating self- and co-regulation strategies, clarifying boundaries, and introducing grounding and meditative practices all function to better equip individuals (and practitioners alike) to approach the experience with steadiness and trust.

Intention is another recurring thread. Often misunderstood as determining the content of a psychedelic experience, intention is better understood as offering a guiding orientation rather than a script. Unlike conventional pharmacotherapy, psychedelic therapy requires active engagement: participants must bring their histories, vulnerabilities, and values into the process to help inform their motivations, as well as plan for long-term support.

Inevitably, the subject of preparation raises deeper philosophical questions: What does it mean to be prepared? Can one ever truly be ready to plunge into the unknown? As explored in today’s Issue, preparation is less about eliminating uncertainty than about cultivating readiness: the conditions that inform intention, build trust, and enable safe navigation and surrender to the experience.

In Practice: Rosalind McAlpine on Psychedelic Preparedness

Each Issue, In Practice brings you voices from across the psychedelic practitioner landscape, shedding light on the realities of working in this field. From pathways into the space to navigating client safety and avoiding practitioner burnout, we will bring you broad perspectives on pertinent themes to psychedelic practice.

In today’s Issue on preparation, we spoke with Dr. Rosalind McAlpine, who generously shared her insights and reflections. Based in the UK, Rosalind’s work centres on psychedelic preparedness and the neural and subjective effects of substances such as psilocybin. She is the co-developer of the Psychedelic Preparedness Scale (PPS) and currently leads trials of the Digital Intervention for Psychedelic Preparation (DIPP) – two initiatives that feature in the conversation below.

Dr. Rosalind McAlpine, Psychedelic Researcher and Co-Developer of the Psychedelic Preparedness Scale

At its core, I think preparation is about trust. Not blind optimism that things will go well, but something deeper - a trust that you can be with whatever arises.

What Does it Mean to be Prepared for a Psychedelic Experience?

The Psychedelic Practitioner: What does it mean to be successfully ‘prepared’ for a psychedelic experience? Can one ever be truly prepared for such an experience?

Rosalind McAlpine: At its core, I think preparation is about trust. Not blind optimism that things will go well, but something deeper – a trust that you can be with whatever arises. Trust in yourself to stay present when things get strange or difficult. Trust in the people around you to hold the space. Trust in the process, even when you don’t understand what’s happening.

That trust is what allows you to say yes to the experience. But there’s the yes you give before – the informed consent, the decision to take the substance. And then there’s something else entirely: the yes that happens during the experience itself.

This second yes isn’t really a decision at all. It’s more a quality of allowing. A felt sense of opening rather than bracing. You know it when it’s happening – there’s a softening in your body, a release of resistance, a sense of “okay, I can be with this”. And yes breeds more yes. When you stop fighting and let yourself surrender into whatever is arising, that very act of surrender seems to make it easier to keep surrendering. The experience starts to move through you rather than crashing against you. It has a momentum to it, almost like falling – once you let go, the letting go itself carries you further.

This is different from the false confidence of someone who says “I’m completely ready, I know exactly what to expect!” That brittleness, that certainty – it actually prevents this kind of yes from emerging. Real preparation involves knowing you don’t know, and finding that tolerable. The person who says “I’m nervous but I trust myself and the people around me” – they might be the one who can actually access this surrender when they need it.

So what is preparedness, really? In our research, we define psychedelic preparedness as a state where individuals feel psychologically, physically, and socially ready for both the content and consequences of the experience. But that readiness isn’t about control or certainty. It’s about having done the work beforehand – understanding the substance, tending to your mental and physical state, building genuine trust with your guides, creating a safe container – that allows you to find that felt sense of yes when you’re actually in it. When something frightening emerges, when your sense of self is dissolving, when you meet something you didn’t want to see, you can soften into it rather than contract against it. You can let the experience move you.

Can you be truly prepared? Yes, I think so. But preparation isn’t about eliminating the unknown. It’s about building enough trust that when you’re in the depths of it, you can surrender. You can find your way to that embodied yes, that quality of allowing, and let it carry you through.

Readiness isn’t about control or certainty. It’s about having done the work beforehand - understanding the substance, tending to your mental and physical state, building genuine trust with your guides, creating a safe container.

How Do You Know If Someone is Prepared?

Editor’s Note: The Psychedelic Preparedness Scale (PPS) is a validated self-report measure developed by Rosalind and colleagues to evaluate an individual’s readiness for a psychedelic experience. Available in both retrospective and prospective formats, the PPS comprises 20 items grouped into four domains: knowledge-expectation, psychophysical readiness, intention-preparation, and support-planning.

TPP: You developed the ‘Psychedelic preparedness scale’ (PPS). Why did you see a need for this and how is its real world use going with current trials?

McAlpine: The need came from a pretty glaring gap in the research. Papers would say therapeutic effects are “dependent” on preparation, it’s “key for maximising benefits”, but when you looked into it, it was all based on clinical intuition and observation. There was no systematic evidence base. Clinical trials all had ‘preparation’ phases, but they were essentially black boxes: poor reporting standards, vague descriptions, no investigation into which specific aspects actually related to outcomes. You’d have blog posts giving tips (which were often not bad!), but no way to know what actually worked, or for whom.

So we needed a way to measure preparedness – to define it, quantify it, and then use that to ask: does this state actually predict anything meaningful? Which facets of preparation matter most? How do different approaches compare? You can’t really answer those questions without a validated measurement tool.

We needed a way to measure preparedness - to define it, quantify it, and then use that to ask: does this state actually predict anything meaningful? Which facets of preparation matter most? How do different approaches compare?

The other driving force was making sure it wasn’t just my perspective as an individual researcher. So we used a co-production approach throughout, involving experts, people with lived experience from previous clinical trials, multiple rounds of Delphi consultation, and focus groups. The idea was to create something that actually reflected what matters to stakeholders, not just what I thought would be important.

In terms of real-world use, it’s been really encouraging. It’s currently being used in over 20 retreat centres across South America and Europe, in about six ongoing clinical trials that I know of, and obviously in our research at UCL. The fact that it’s being adopted this widely suggests it’s filling a need – perhaps giving practitioners and researchers a common language and framework for thinking about preparation systematically. Which is pretty cool!

[The Psychedelic Preparedness Scale is] currently being used in over 20 retreat centres across South America and Europe, in about six ongoing clinical trials that I know of, and obviously in our research at UCL. The fact that it’s being adopted this widely suggests it’s filling a need.

TPP: Have you come across things that still can’t be captured or predicted by the scale?

McAlpine: Oh, loads. The PPS is a self-report questionnaire – 20 items asking people to rate themselves on things like their knowledge, trust in the process, intention clarity, support systems. But there’s probably so much beyond that.

One thing I find really interesting is this question: okay, you might assess yourself as super ready, but how would other people perceive you? How would your partner, friend, or sister rate your preparedness? We see this limitation across so many self-report measures in psychology – there’s this gap between how we see ourselves and how others see us. It would be fascinating to explore inter-rater reliability here. You could imagine a clinician-rated version, like we use for other clinical assessments, but maybe there’s something valuable in having multiple perspectives – acquaintances, close relationships, practitioners – all contributing different angles.

Then there are less explicit forms of preparedness we might capture through other methods. The PPS captures a specific state we might describe as preparedness, but perhaps there are aspects of traits and states we could pick up through implicit methods. We’re doing some of this with experience sampling – using a Telegram bot to ping people a few times a day, capturing their natural reflections. Jo Kuc in our lab has been analysing not just the content of what people say, but how they say it – things like language structure, pitch, emotional tone. It’s this covert way of tapping into psychological states that people might not explicitly report on a questionnaire.

And obviously, we’re not capturing any physiological markers with this scale – things like heart rate variability, brain-based measures, gut functioning etc. There could be some really interesting biomarkers or predictors there that tell us something about readiness that self-report simply can’t access.

Scaling Preparation: Early Lessons from DIPP

Editor’s Note: The Digital Intervention for Psychedelic Preparation (DIPP) is a modular protocol designed to support individuals preparing for psilocybin sessions. Developed as a practical, evidence-informed tool, DIPP draws on the four-factor model of psychedelic preparedness established in the Psychedelic Preparedness Scale (PPS). Its design was shaped through interviews with participants and prospective psilocybin users, ensuring the program reflects real-world needs and experiences.

The model stands apart from established psychedelic protocols, which often rely on multiple in-person preparation sessions with a therapist – a process that can be logistically challenging. Instead, it offers a more scalable approach to preparation. Certain nuanced elements (such as navigating therapeutic touch) are still addressed in a dedicated in-person session the day before dosing. The intervention is currently being trialled by Rosalind McAlpine and her research team at University College London.

Over 21 days, there are 69 tasks to complete - daily practices, mood ratings, journal entries, plus weekly psychoeducation and planning tasks.

TPP: Have you come across any challenges with the DIPP model? How are participants faring?

McAlpine: Honestly, the biggest challenge was wondering if people would even do it. It’s a lot. We’re about halfway through the feasibility trial now, and so far it’s going surprisingly well – but we had some (healthy?) doubts going in.

The intervention is pretty intense. Over 21 days, there are 69 tasks to complete – daily practices, mood ratings, journal entries, plus weekly psychoeducation and planning tasks. For anyone who works in intervention research, that’s an insane amount to ask of people. Our prespecified adherence threshold was 70% of participants achieving 70% completion, and, so far, we’re seeing well above that.

When we present this work, the first reaction is always: “No one’s going to do that much!” But they are! I think there’s something about having a clear endpoint that changes the equation. It’s not “do this for your mental health indefinitely” – it’s 21 days building toward something specific and meaningful: your psilocybin session. When people understand exactly why they’re doing something and can see the finish line, they’ll put in quite a lot of effort.

[Editor’s note: My mum recently completed this same preparation protocol before embarking on her first psilocybin experience under Rosalind and her team’s guidance. Despite joking about a ‘slightly annoying bot’ that pinged her phone occasionally, she genuinely enjoyed the 21-day rhythm of journaling and daily music and mood exercises. From my perspective, she seemed very well-prepared, and definitely ready to surrender to the experience. – Alice Lineham]

Now, these are healthy volunteers. I’m not claiming clinical populations would necessarily manage this intensity. But it’s made me rethink assumptions about what people will commit to when there’s clear purpose, structure, and a goal they actually care about. Whether that translates to less controlled settings without the tracking and accountability, I don’t know yet – but it’s encouraging.

When we present this work, the first reaction is always: “No one's going to do that much!” But they are! I think there’s something about having a clear endpoint that changes the equation. It’s not “do this for your mental health indefinitely” - it's 21 days building toward something specific and meaningful: your psilocybin session.

Universal Model or Bespoke Preparation? The Future of DIPP

TPP: Do you expect the DIPP protocol will be adapted for different indications, compounds, or settings? Or, do you think there’s hope for creating a model that can be used universally?

McAlpine: I’m actually quite optimistic about DIPP as a framework. The way we developed it – through co-production, asking broadly about psychedelic preparation rather than one narrow context – was deliberately meant to create something adaptable. And the backbone of it, the temporal structure, the modular approach organised around those four PPS factors, the progressive daily engagement, I think that could absolutely work across different contexts and should be tested more widely.

What we’re evaluating now is this specific version: psilocybin, healthy volunteers, research setting. And the feasibility data is really encouraging. But the content within that framework would likely need careful adaptation for different situations.

For 5-MeO-DMT, you might keep the 3-week structure and daily practices, but what those practices emphasise would probably be quite different, perhaps more somatic preparation, breathwork, preparing for that incredibly rapid dissolution rather than a 6-hour journey. For someone with PTSD, the weekly modules might need to weigh safety planning and grounding techniques more heavily. For severe depression, you might need explicit content around managing expectations and preparing for the possibility the treatment doesn’t work as hoped. But these are just hypotheses, we’d need to actually test what matters for different populations.

The exciting vision (and this is genuinely what I’d love to see) is eventually having enough data to make DIPP truly bespoke. Inputting all the relevant details about the person, their history, the compound, the clinical presentation, the setting, and having a preparation protocol that’s personalised for that specific situation. Not just “here’s the generic 21-day program” but “here’s what you specifically need based on everything we know about what works for people in your situation”.

That requires significantly more research and, frankly, funding! We need to understand the mechanisms better, test adaptations systematically, figure out which elements are genuinely universal versus which need tailoring. But as a framework for getting there, I think DIPP has real potential.

The exciting vision (and this is genuinely what I’d love to see) is eventually having enough data to make DIPP truly bespoke. Inputting all the relevant details about the person, their history, the compound, the clinical presentation, the setting, and having a preparation protocol that’s personalised for that specific situation.

Advice to Practitioners

TPP: What advice would you give to practitioners, or those supporting individuals in preparing for psychedelic experiences?

McAlpine: I think the most important thing is understanding what you’re actually there for as a practitioner. The systematic preparation, as we’re showing with DIPP, can largely be delivered through structured programs. But people still seek practitioners for something else. And I think this reminds me of research on psychosis, where patients described needing staff to look on them with “good eyes”. Not to see them through the lens of diagnosis or pathology, but as capable, ordinary human beings even in their most vulnerable states. They needed staff to be normal, steady, present – not mystifying, not reducing them to symptoms, just genuinely human.

I think the same applies here. People aren’t seeking you for more content or frameworks. They’re seeking someone who can help them trust themselves and the process. And you do that by genuinely seeing them – not as “the participant” or “the patient” or through your theories about what psychedelics are or what transformation should look like, but as a capable person choosing to do something profoundly significant with their life.

Be normal. Be steady. Be present. Your job isn’t to have all the answers or to make it safe or controllable. It’s to be there at the edge of genuine uncertainty without making it heavier than it needs to be, and without reducing them to anything less than whole.

Be normal. Be steady. Be present. Your job isn’t to have all the answers or to make it safe or controllable. It’s to be there at the edge of genuine uncertainty without making it heavier than it needs to be, and without reducing them to anything less than whole. That steadiness, that capacity to see them with “good eyes” as someone capable of meeting what’s coming – that helps them access their own trust rather than becoming dependent on yours.

Use the frameworks and evidence we’re building. Be systematic about what matters. But remember that underneath all of that, you’re a human helping another human prepare for something genuinely mysterious. That’s not a technical role. That’s profoundly human. And it requires you to see the person in front of you clearly – as whole, as capable, as someone who can meet the unknown. That’s the work that can’t be systematised. That’s why they want you there.

Use the frameworks and evidence we’re building. Be systematic about what matters. But remember that underneath all of that, you're a human helping another human prepare for something genuinely mysterious. That’s not a technical role. That’s profoundly human.

Views from the Field: Preparation Begins with the Therapist

In psychedelic therapy, preparation is often described as the first phase of care. But preparation doesn’t belong only to clients, it begins with the therapist. The attitudes we ask clients to bring into their psychedelic experiences are the same attitudes therapists must cultivate within themselves long before a dosing session begins.

High-quality training programs reflect this truth. They don’t simply teach techniques; they create a learning environment that mirrors the therapeutic arc of preparation, experience, and integration. Through guided exercises, reflective journaling, shadow work, and supportive dialogue, trainees learn to approach uncertainty with curiosity, self-awareness, and steadiness. These are the same inner qualities that help clients feel safe, trust the process, and engage the depth of their experience.

When trainees feel held in a space that values reflection, connection, and psychological safety, they internalize what it means to create that same container for others. Training becomes an opportunity to embody presence, refine self-regulation, and build the capacity to meet challenging material with compassion.

This approach reframes training as more than a prerequisite. It is an ongoing, living practice that shapes how therapists show up throughout their careers. Just as psychedelic insights only transform lives when integrated into daily experience, the knowledge and skills gained in training become most meaningful when supported by community, ethical grounding, and continual self-reflection.

Ultimately, preparation in psychedelic therapy is relational. Therapists model the openness and steadiness they hope to see in their clients. When training honors this full arc, it prepares practitioners to walk alongside clients with integrity and care, laying the groundwork for truly transformative therapeutic work.

Elizabeth Nielson, PhD, Fluence Co-Founder and CEO

Practitioner Voices

Dr. Nielson’s perspective highlights an important imbalance: while participant preparation is widely discussed, the readiness of those accompanying them often remains underexplored. Despite its significance, there remains little consolidated guidance on how practitioners should effectively prepare themselves to hold space for psychedelic experiences. Trial protocols and reports rarely detail what happens in the therapy room, and manuals – save from a handful of comprehensive, experiential models – often omit teachable instructions.

To better understand how preparation is understood, lived, and practiced, we reached out to our network of psychedelic practitioners.

Dr. Chantelle Thomas, U.S. based clinical psychologist and psychedelic facilitator, trainer, and supervisor at UW School of Medicine and Public Health

Dr. Henrik Jungaberle, Executive Director of the MIND foundation, has worked to develop, facilitate and train practitioners on a number of psychedelic-related programmes

Dr. Rosalind McAlpine, post-doctoral researcher with a specific interest in psychedelic preparedness, currently running trials at University College London

Tom Shutte, psychotherapist, clinical supervisor, and psychedelic research therapist, currently a lead therapist on several UK-based psychedelic clinical trials

What Does it Mean to be Prepared as a Psychedelic Practitioner?

Preparedness As: Inner Work

The first pertinent theme that emerged from our four practitioners was the importance of one’s own inner work. Dr. Chantelle Thomas frames preparedness as “fundamentally about cultivating self-awareness and non-agenda”, noting that “practitioners must be highly attuned to personal biases or desired outcomes that could inadvertently steer the participant.”

Dr. Rosalind McAlpine agrees, but challenges the very notion of neutrality. She contends that “[our] beliefs about what psychedelics are, what healing looks like, what’s supposed to happen are not neutral”. For McAlpine “[practitioners are] actively part of the process. Being aware of your frameworks and not treating them as universal truth seems really important.” “But it’s really hard work!”, she added: “Our beliefs are so embedded we don’t always see them.”

This recognition of embedded belief systems extends further, with McAlpine emphasising the need to grapple with “not-knowing, to the possibility of fundamental change”. She argues that one does not need to be perfectly comfortable with uncertainty, but must have “grappled with it enough that you can be present with someone else’s process without needing to manage or control it.”

Building on this recognition of limits, Dr. Henrik Jungaberle maintains that “preparedness demands ethical clarity, well‑defined boundaries, and a healthy dose of epistemic humility when it comes to so‑called ‘noetic insights’”. He advocates that practitioners adopt a stance of “ontological agnosticism”: an awareness that ultimate questions about reality cannot be answered with certainty, and that one’s own and others beliefs must be acknowledged without being treated as universal truths.

Finally, McAlpine adds a more contested dimension: the role of personal psychedelic experience. She believes it “probably helps” to have had such an experience, “not because you need to have ‘been there’ to guide someone, but because these experiences are so profoundly difficult to grasp without encountering them yourself”. Interestingly, this was not raised by other practitioners despite 85% (94/111) of surveyed psychedelic researchers reporting experiences with classical psychedelics, and the topic remaining an ongoing point of contention in the wider literature.

Preparedness As: Training and Skills

While McAlpine believes preparation is “less about specific training or credentials and more about ongoing inner work”, Jungaberle emphasises that preparation is primarily about practical competence, rather than “spectacular personal experiences”. For him, “the person in the room needs a solid grounding in mental disorders, case formulation, and therapeutic relationship”, arguing this is “more than [just] holding space”.

Jungaberle adds that practitioners require a solid grasp of pharmacology, contraindications, and emergencies, alongside “skills in shaping set and setting, managing heightened suggestibility, and supporting challenging experiences with minimal but precise interventions”. Thomas agreed, noting that “preparedness…involves cultivating a solid therapeutic alliance and…relational safety”, mentioning these sessions demand that she employ all [of her] clinical skills”.

Preparedness As: Relational Attunement and Presence

Attunement emerged as a central theme across practitioners. Tom Shutte highlights the particular demands of working with empathogens, where practitioners may “need to remain attuned for a long period of time to a patient who may be sharing experiences they have never felt safe enough to share before”. He adds that “you also need to be prepared to maintain an attentive, and non-reactive presence in receiving strong positive or negative projections.”

Thomas echoes this emphasis, noting that attunement for practitioners involves tracking “not only what is being said but also what is being felt”. She also describes attunement as potentially catalytic: under optimal conditions, “a prepared practitioner can facilitate the client becoming more attuned with their innate capacity for self-healing”.

Preparedness As: Practical Considerations

Practitioners also stress the mundane but crucial logistics that underpin effective presence. McAlpine reminds us that “these sessions are long. You need to be genuinely rested, calm, able to be present for eight or more hours, in the case of psilocybin”. She warns that exhaustion, stress, or distraction can significantly impact the process: “the quality of your presence matters”.

Shutte echoes this, noting that participants should be “sufficiently resourced” to sustain the “energetically and emotionally demanding work” required by both empathogens and “classic psychedelics [that] may require holding space for hours of silence whilst a patient is inwardly focused.”

Jungaberle adds a collective stance, stressing that effective preparation also means working as part of a team. For him, the onus is on practitioners to “collaborate effectively” as “psychedelic therapy is a cooperative sociocultural practice, not a heroic psychonautic journey”.

What Is Your Advice to Practitioners Preparing Individuals for Psychedelic Experiences?

Engage in Continuous Learning, Supervision, and Personal Work

A number of respondents urged that preparation is something of a continuous process, with Shutte advising practitioners on the importance of “ongoing, good-quality supervision”. Thomas agrees, stressing that “continuous professional development” is critical, and that practitioners must “remain aware and up to date on the evolving legal and regulatory landscape…to ensure best practices.” For her, “preparedness is a commitment to a lifelong learning process that grounds the practitioner in competence, humility, and wisdom.”

Both Shutte and Thomas also highlight the importance of personal therapy and inner work. Thomas iterates that “rigorous personal work—including addressing one’s own psychological ‘shadow’ through therapy or other self‑reflective practices—is necessary to better track and understand how relational dynamics impact sessions.” Shutte echoes this, noting that personal therapy is crucial for “a safe and sustainable practice.”

Attend to Your Blind Spots and Fantasies

Thomas cautions practitioners about “becoming more aware of how blind spots and fantasies of perfection manifest”, emphasising that this awareness is crucial for “increasing [levels] of relational safety”.

Shutte builds on this, advising that in the run-up to sessions practitioners should “reflect on any fantasies or expectations formed during preparation and do your best to bracket them [as] they are usually off the mark and can interfere with being genuinely present to the patient’s process.”

Practice Attunement and Intention

For Thomas, attunement is a critical edge: “learn to track and attune to the participant’s experience of their body and internal sensations, [this] is vital in non-ordinary states of consciousness and sometimes neglected in other modalities”.

Shutte offers complementary practices, suggesting that: “centering breaths can help regulate and attune nervous systems, strengthening the therapeutic container”, and adds that “immediately before the session” it is important to “take time to connect with your intention for supporting the patient”.

Structure Your Approach

Jungaberle advised a more structured approach, urging practitioners to “think in terms of two phases”. The first phase involves building a “working alliance, [clarifying] problems and goals, and [assessing] whether a psychedelic session is clinically necessary”. The second focuses on “targeted preparation for the altered state itself”, which includes “psychoeducation, shaping expectations… and collaboratively formulating values-based intentions”.

He also stresses the importance of utilising “non‑avoidant strategies” to help patients face adverse emotions, such as “mindful acceptance, ‘leaning into’ difficult material, basic breathing, and grounding skills.” Finally, Jungaberle insists that “it is essential to plan for integration and harm‑reduction from the outset, as some people will continue to engage with psychedelics or related communities beyond the formal treatment.”

Remember the Practicalities

Finally, Shutte takes it back to basics: “be well rested, grounded and relaxed going into a session. Aim to manage your personal stress levels in the run-up and to prioritise good-quality sleep the night before as well as time to rest afterwards”. He adds that “light physical exercise on the day can support embodiment”, and notes the importance of making time for a brief check-in with your dyad or larger team before sessions.

Have Your Say

What do you think are the most important considerations when preparing someone for a psychedelic experience, both for the patient and the practitioner? We’d love to hear your thoughts: email TPP@psychedelicalpha.com.

Going Global

Going Global is your round-up of developments from around the world, from policy reform and insurance coverage decisions to shifting cultural attitudes and global access initiatives.

As we look back on 2025, momentum has certainly been building across continents. Research pipelines continue to expand beyond the West, conferences feature an increasingly diverse global speaker base, and surveys evidence shifting public attitudes. (See the Psychedelic Perceptions Tracker for more on how the class of drugs are perceived across the world.)

Access in Oz: Australia Funds Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy for Veterans

In a world first, Australia’s Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) announced it will fund psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP) for the treatment of mental health conditions among its veteran population. The approved treatments include MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD and psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression.

As noted by Psychedelic Alpha, this decision comes just over a thousand days after the country down-scheduled these compounds (prior to their approval as pharmaceutical products) when used in these conditions by authorised psychiatrists.

To qualify, veterans must have already undergone multiple standard treatment options and demonstrated an inadequate response. Crucially, treatment with these compounds must occur within a model that includes intensive psychotherapy. The centrality of psychotherapy to the process echoes frameworks seen in other pre-marketing authorisation access models, including Norway’s state-funded IV ketamine therapy protocol as well as Germany’s compassionate access programme.

As with many of these early initiatives, cost remains a critical consideration, especially given a course of treatment is estimated at AUD $20,000 (approximately U.S. $13,000). Under this new program, however, the DVA will cover the cost for eligible veterans, funding up to three dosing sessions per individual, with any additional sessions requiring approval from the DVA’s Chief Psychiatrist.

While the DVA’s decision reflects public sector support, a $10 million pledge from the country’s largest private health insurer Medibank to fund MDMA and psilocybin therapies suggests growing confidence from the private sector, too.

All Eyes on D.C.: Psychedelic Approvals and Policy Movement Expected to Accelerate

As alluded to in our Vitals entry on the same topic, things are heating up in the U.S. as it pertains to psychedelic policy, approvals, and funding.

Psychedelic Alpha now expects to see up to three FDA approvals of psychedelic compounds in the next 18 months, the first of which could come next year. A large portion of the FDA Division of Psychiatry’s workload is reviewing psychedelic-related drug development projects that are underway, and policy movement at the agency could speed things up.

One of those shifts is an agency-wide move to expecting just one pivotal study from sponsors before assessing a drug for a potential approval. At the moment, FDA expects two pivotal trials (which are usually Phase 3 studies) by default, though in practice it often reduces this to just one. But psychiatric drug candidates have generally needed at least two studies to secure approval, which means this apparent moving of the goalposts at the agency could accelerate approval decisions for the class.

Psychedelic Alpha also expects to see other policy changes or clarifications at the FDA that will streamline the review of psychedelics, as well as other rapid-acting mental health interventions.

Outside of the FDA, lobbyists and lawmakers are pushing for policy reforms at the federal level, too. Earlier this month, the Freedom to Heal Act was introduced by a bipartisan group of lawmakers. It aims to ‘fix’ a ‘gap’ in the federal Right to Try law which precludes the availability of Schedule I drugs through the scheme. If this bill passes, patients with life-threatening illnesses who have tried all other options could be eligible to receive certain psychedelics under Right to Try legislation. Other federal bills are expected to be introduced this month.

On the funding side, ARPA-H, which is the U.S. government’s healthcare moonshot funding agency, has set aside more than 10% of its annual budget to support a new initiative dubbed Evidence-Based Validation & Innovation for Rapid Therapeutics in Behavioral Health (EVIDENT). Through the program, the agency aims to realise the elusive goal of ‘precision psychiatry’: developing objective endpoints for behavioural health disorders and rapid-acting interventions, as well as codifying non-drug factors that might drive patient outcomes.

There’s obvious relevance for psychedelic therapies here, too. Not only are they mentioned as key interventions the initiative hopes to support the development of, but certain objectives of EVIDENT seem tailor-made to grapple with persistent questions in the field. Take technical area 2, for example, which focuses on characterising mechanisms of rapid, in-session change. Specifically, the agency says it hopes to explore approaches to monitoring “dyadic interactions between patient and facilitator”, with the goal of “discover[ing] interpersonal and therapy dynamics that increase effectiveness.” It hopes to understand the contribution of not only the “therapists, guides, monitors”, but also the physical setting, to a patient’s real-time clinical change. In simple terms, the agency is looking to characterise the contribution of set and setting.

Over at the VA, meanwhile, a 240-patient Phase 3 trial of Compass’ synthetic psilocybin for veterans with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) has been registered. It has an expected start date in June 2026.

It looks set to be a very busy 2026 in the U.S., with Psychedelic Alpha continuing to cover the regulatory momentum closely.

Guidelines Emerging: Czechia Prepares for Psilocybin Therapy Rollout

In June, Psychedelic Alpha reported on reforms to Czechia’s criminal code that included an amendment that contemplated the legalisation of psilocybin’s use in certain medical contexts. Following the passage of the reforms, we had been waiting to see how the psilocybin-related provision would be operationalised. We had expected that to happen in time for the new year.

Indeed, news is now emerging from the European nation that patients with certain mental health disorders who have tried available treatments will be able to seek out psilocybin therapy in 2026. Guidelines for the use of the drug have been drafted by the Czech Medical Association’s Psychiatric Society, which stipulate who may prescribe and administer psilocybin and to whom.

But, as with similar programs in other countries, reimbursement remains a hurdle, though negotiations with insurers are apparently underway. That means that the broader availability of psilocybin therapy in Czechia remains an open question, which we will be following closely in the new year.

Research Radar

Here, we dive a little deeper into some of the most pressing research topics shaping the world of psychedelic practice. Each item ends with the Bottom Line for those of you who are pushed for time or want our read on the subject.

Mixed Signals: Recent Studies Complicate the (Es)Ketamine Picture

Psychiatric interest in ketamine has been rising steadily since the discovery of its rapid antidepressant effects at the turn of the century. There now exists a sizable body of research into the compound and its enantiomers, with a number of studies touting marked benefits over and above conventional pharmacological treatments.

More recently, however, both clinical findings and societal debates are becoming increasingly fractured. On one side (of the Atlantic): U.S. Border Patrol seizures and media alarm frame ketamine as an “animal anesthetic dangerously abused by drug users, and by sexual predators”. At the same time, an increasing number of companies are offering it both in-clinic and at-home. On the other side of the pond: Norway has moved to publicly fund it as a treatment for depression, while the UK weighs its reclassification to Class A, the most stringent of drug categories. It’s a confusing time to be ketamine.

Ketamine vs Esketamine?

Following its approval in 2019 for treatment-resistant depression (TRD), Johnson & Johnson’s esketamine nasal spray, Spravato, has achieved blockbuster drug status with revenues of over $1 billion annually. But recent data has begun to question whether it is superior to racemic ketamine which, although not FDA-approved for any mental health condition, is being increasingly used off-label for TRD.

In September, Robert Meisner and colleagues from Harvard Medical School published a retrospective chart review comparing the antidepressant effects of intravenous (IV) racemic ketamine infusions with intranasal (IN) esketamine (Spravato). 153 treatment-resistant patients were seen at McLean Hospital, each of whom had failed at least two conventional antidepressant trials. Of these, 111 received IV ketamine and 42 received esketamine.

Broadly speaking, the IV ketamine group showed significantly greater reductions in depression scores, and achieved them more quickly. More specifically, patients in the IV group saw a 49.22% reduction on the primary outcome measure (QIDS-SR) by dose 8, compared to 39.55% in the IN group – a nearly 10% difference. Notably, while both groups showed significant score reductions, the IV group required only one treatment to reach statistical significance, whereas the IN group needed two, on average.

Similar preferential IV ketamine findings have been echoed in other retrospective studies at Yale and the Mayo Clinic. Interestingly though, the only randomised trial in this area found no difference between the two, but it’s worth noting that the study used a single-dose IV esketamine or ketamine design, limiting applicability to most real-world use, which involves repeated dosing and in the case of Spravato, IN administration.

As an important caveat, Meisner et al.’s report doesn’t include any adverse event data. In a recent commentary, Dr. Samuel Wilkinson notes that, despite IV ketamine’s suspected efficacy advantage, Spravato may present a safer option due to the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program that governs its use.

Another critical tension, as noted by Samuel Wilkinson in an interview with Psychedelic Alpha’s Josh Hardman, is the reimbursement gap: intranasal esketamine has considerably broader coverage compared to IV ketamine, meaning that “patients who get ketamine are going to be wealthier than those who [get esketamine], and we know that wealth predicts clinical outcomes.”

Larger, randomised trials are underway to address the ketamine versus esketamine debacle, including a 400-participant study led by Wilkinson at Yale (NCT06713616). This trial, sponsored by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), a funder of research that produces results applicable to diverse pools of patients and settings, will directly compare Spravato with IV ketamine. Results are expected around 2031.

Ketamine vs Midazolam?

Meanwhile, attention has turned to another looming question: does IV ketamine outperform placebo at all? A recent study published in JAMA Psychiatry—The KARMA-Dep 2 trial, a double-blind RCT conducted by researchers at Trinity College Dublin—examined twice-weekly IV ketamine infusions (up to eight sessions) compared with the active placebo midazolam as an adjunct treatment for inpatients with major depressive disorder (MDD).

Of the 62 participants, final MADRS scores at a six-month follow-up showed no significant difference between groups. Other measures, including self-reports, cognitive assessments, and quality-of-life indices, also failed to distinguish ketamine from midazolam.

Many have weighed in on the study’s null findings, attributing them, at least in part, to the inpatient setting, but this line of critique has featured multiple angles. Some argue the inpatient environment wasn’t therapeutic enough, while others suggest it was so inherently supportive that everyone improved, thereby masking any drug-specific effects.

Dr. Wilkinson leans toward the latter. In the same interview with Psychedelic Alpha, he emphasised that the very nature of inpatient care is likely to have catalysed broad improvements across both groups. As he puts it: “You’re removed from this very stressful environment that you were living in beforehand. You know that people are attending to you… there’s a lot of treatment going on.”

Conversely, a former clinical trial manager for the study in question flagged the biomedical setting as a potential contributor of why IV ketamine failed to outperform midazolam, noting the absence of preparatory or integrative support, and the lack of staff trained in psychedelic therapy. This tension revives a broader qualm in the psychedelic field: the role of non-pharmacological factors or the ‘set and setting’.

Ketamine with Preparation vs no Preparation?

Many protocols employed with classic psychedelics include several hours of psychological support in the form of preparation, involving comprehensive education and support, along with dosing support followed by integration sessions. (Es)ketamine, on the other hand, typically entails no more than a two-hour long Spravato or IV session for which preparation often entails basic advice on things like hydration and arranging transportation. More comprehensive Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP) models do exist, though, with frameworks like the Montreal Model more akin to classic psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy models. They feature structured preparation including psychoeducation, goal setting, and mindfulness, along with post-dosing integration support.

However, save for a small number of preliminary studies suggesting promise, the relative contribution of structured preparation and integration with both IV ketamine and esketamine remains unclear. Very few trials include mention of a structured psychotherapy model, and others omit this piece entirely. Meanwhile, few formal programs exist for KAP certification; especially when compared to other psychedelic training programs. It will be curious then, as clinical interest in KAP accelerates and clinics continue to multiply, to see if ketamine’s benefits have been misconstrued due to investigation outside of the psychotherapeutic context.

Bottom Line: The jury is out on a number of ketamine-related queries. IV ketamine seems to show stronger and faster antidepressant effects than esketamine, but trial results remain mixed, with some questioning whether ketamine outperforms an active placebo at all. On the other hand, esketamine is potentially more accessible due to its on-label approval for TRD and some reimbursement, and its REMS restrictions may make its use safer than IV ketamine. Crucially, most research overlooks the non-pharmacological factors employed in (es)ketamine treatment, including the quantity, quality, and type of psychological support. As we move forward, the real question for practitioners may not be which drug is superior, but under what conditions, with what support, and for which patients these treatments work best.

A Microdosing Mirage? Microdosing Fails to Outperform Placebo In Largest Trial Yet

As alluded to in Vitals, above, microdosing advocates have suffered another setback. As reported by Psychedelic Alpha, MindBio’s recent Phase 2b trial has added to a growing body of evidence questioning the therapeutic value of sub-perceptual dosing. The triple-blind trial involving 89 participants randomised to receive either take-home LSD or caffeine (active placebo) delivered a negative readout last month. Expressing “surprise” and “disappointment”, Hanka conceded: “LSD is not effective at treating patients with Major Depressive Disorder”.

Although both groups showed marked improvements in their depression scores, there was no significant difference between them at the 8-week primary endpoint. If anything, the active placebo (36% reduction) slightly outperformed LSD (30% reduction). Not a single primary or secondary endpoint was met, the company’s CEO said.

As discussed in Psychedelic Alpha’s earlier coverage, some microdosing advocates may be quick to critique the trial design, arguing that the dose was too low, the protocol too brief, or that it failed to capture real-world benefits. Yet the trial was intentionally designed with ecological validity in mind, incorporating features such as self-titration and at-home dosing to mirror how microdosing is typically practised in the ‘real world’.

Indeed, despite the current lack of peer-reviewed publication precluding deeper scrutiny of the data, this Phase 2b trial is the largest and most rigorous study to date investigating microdosing for depression, and the results are fairly unambiguous.

It was just weeks prior that things were looking good for the small biotech startup when it released data from its small open-label Phase 2a study reporting a 60% reduction in depression scores sustained for up to six months. That built on positive reports from the company’s healthy volunteers study, which added to a body of observational research touting benefits for attention, mood and creativity. However, the folks in these observational trials were all aware they were microdosing psychedelics, so it’s difficult to rule out the contribution of expectancy.

MindBio’s results now join a somewhat longer queue of null findings. A recent longitudinal analysis published in Neuropharmacology examined two double-blind psilocybin microdosing trials (n=60) in semi-naturalistic settings. Although participants described their experiences as predominantly positive, the conclusion was marked: microdosing psilocybin did not enhance cognitive or emotional functioning beyond placebo.

Similarly, a large systematic review of 14 studies representing 1,614 participants published last month deduced no overall cognitive benefit of microdosing. And, MindMed’s Phase 2a trial also failed to show efficacy when testing LSD microdosing for ADHD, a result which prompted the company to abandon its low-dose pipeline altogether.

Bottom Line: It’s not looking good for micronaughts, with data increasingly suggesting that expectancy and placebo effects may underlie many of the previously perceived benefits of the practice. For many practitioners, these findings may underscore a long-held intuition: that the psychedelic experience itself, in all its messy intensity, just might be integral to the therapeutic experience after all.

What Do Providers Prioritise?

Forty psychedelic providers spanning 16 institutions completed an anonymous survey regarding challenges they have encountered when administering psilocybin and/or LSD in research settings. Having collectively worked on over 1,600 psychedelic sessions, the respondents cited the most common difficulties among patients as: intense dysphoria (42% of respondents), disappointment with the intervention (25%), and re-engagement with traumatic experiences (17%).

When asked how many hours of support they believed to be necessary in psychedelic treatment models, responses averaged 4.8 hours for preparation and 5 hours for integration. A minimum of 10 hours for both prep and integration was noted as critical for individuals with serious mental illnesses who were undergoing psychedelic therapy for the first time. For context, Usona Institute’s Phase II protocol involved approximately 11 hours across preparation and integration, whereas Compass Pathways’ Phase II included just 4.5 hours.

Providers overwhelmingly emphasised that the ideal conduct of psychedelic treatments must be context- and participant-specific. For example, a majority (70%) felt that those with PTSD or trauma histories require extended or more comprehensive forms of psychological support, making it by far the condition most associated with concern. Concern was also noted for participants with limited social support, with emphasis that psychological support for these individuals be tailored, and increased, accordingly.

This draws on a broader question surrounding whether treatment frameworks should be tailored to individual participant demographics and lived experiences. Chara Caruthers, a psychedelic therapist speaking at ‘The Future is Psychedelic’ at King’s College London last month, argued that they should, pointing out that neurodivergent individuals are often excluded from current models. Camille Barton, speaking on the same panel, highlighted the lack of attention that is currently afforded to disabled participants, calling for relevant parties to take “time and care to give neurodivergent and disabled individuals as much information as possible to discern if that’s actually going to be a space that works for them.”

Rosalind McAlpine, who we spoke to earlier in this Issue, envisions a future in which preparation protocols become truly bespoke: drawing on “relevant details about the person, their history, the compound, the clinical presentation, the setting, and having a preparation protocol that’s personalised for that specific situation.” Although this notion goes against medicine’s broader trend toward standardised practice, the survey authors caution that regulatory frameworks favouring standardisation in psychedelic care may inadvertently heighten the risk of adverse events or lead to less impressive outcomes.

Findings in Brief

📈 Second 5-MeO-DMT Dose Strengthens Response: AtaiBeckley, the biotech formed through the recent merger of atai Life Sciences and Beckley Psytech, has announced positive Phase 2b results from the Open-Label Extension (OLE) of its Phase 2b trial of its intranasal 5-MeO-DMT (BPL-003) in treatment-resistant depression. The OLE offered all participants a 12mg dose of the drug candidate following the blinded phase, where they had received either 0.3mg, 8mg, or 12mg. Building on the positive blinded data released in July, the 12mg dose produced robust reductions in depression severity (MADRS scores) across all groups. Notably, those who received the 8mg in the blinded phase achieved a remarkable 22.3-point drop on average 8 weeks after the second active dose. The safety profile remained broadly consistent with prior studies, though there was one serious drug-related adverse event. The company hopes to launch a Phase 3 program in Q2 2026.

🧠 Switching Off to Survive: A recent study from Guy Simon and colleagues conducted in-depth interviews with 45 survivors from the October 7th Nova Music Festival attack in Israel. The authors identified a phenomenon they termed “adaptive psychedelic dissociation”, which they describe as a state of emotional detachment in which the psychedelic effects switched off during the attack, leaving survivors with sharpened attention, rapid decision-making abilities, and calm amid a chaotic, life-threatening situation. Whilst this dissociation was felt by many as positive in the short-term, ultimately helping them survive the attack, integration afterwards proved immensely complex. This paper adds to a growing body of research on the event, including findings that attendees using classic psychedelics, compared to no psychedelics or MDMA, experienced lower anxiety and reduced post-traumatic responses several weeks later.

🚫 Too Young to Trip? A scoping review published in The Lancet by a group of ethicists and researchers points to the scarcity of psychedelic-assisted therapy data in under-18s, highlighting what they deem a major evidence gap. Existing studies in this age group focus almost exclusively on ketamine, which, though showing encouraging safety and efficacy signals, is not guaranteed to accelerate broader investigation into other compounds, particularly given its half‑century head start as a licensed paediatric anaesthetic. Administering illicit substances to adolescents is a far cry from the classroom slogan “just say no,” and progress is unlikely to be straightforward as society grapples not only with questions of legality and perceived addictive potential, but also with the biopsychosocial complexities of adolescent development. Editor’s note: Back in 2022, I wrote an article titled ‘Would you let your teenager try psychedelics?’ which explores some of the central arguments both for and against the advancement of psychedelic research in adolescents. – Alice Lineham

Ethics Corner: Preparing Them for What? The Ethics of Shaping Expectations

From informed consent and power hierarchies to therapeutic touch and boundary setting, Ethics Corner explores the nexus where practitioner values, client vulnerability, and evolving norms collide. Expect insights from key opinion leaders, real-world case studies, and candid reflections.

In Today’s Issue, we are delighted to welcome Dr. Eddie Jacobs and Dr. Bryony Insua-Summerhays to the Ethics Corner. We, the Editors, invited Eddie and Bryony to pen this regular column as their combined insights expertly bridge theory and lived practice, offering grounded perspectives on the ethical tensions at the heart of psychedelic work. Each column ends with a question to carry.

For their first Issue as contributors, we asked the pair to introduce themselves before delving into a preparation-related topic…

We come to this column from complementary directions. Eddie holds a PhD in the ethics of psychedelic therapies, and is now at Johns Hopkins’ Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, deepening his grasp of the science and clinical practice so he can build better bridges between ethics and the realities of the work. Bryony is a senior clinical psychologist in training as an analyst, which means she’s spent years in rooms where the rubber meets the road: sitting with what’s actually happening between therapist and client, where tidy ethical frameworks meet untidy humans.

Our shared conviction that guides this column is that ethics isn’t about a credential or a set of rules that you can memorise or master. Readers hoping for prescriptive right answers will find themselves disappointed. As we see it, ethics is something you do, often imperfectly, in real time, under uncertainty. We’ve both encountered situations where the guidelines didn’t quite fit, where competing values pulled in different directions, where we genuinely weren’t sure what the right call was.

This column is for practitioners (and aspiring practitioners) who recognise that feeling. Not because we have answers that you don’t, but because we think the questions are worth taking seriously together. We’re interested in the places where reasonable, thoughtful people disagree – and why this might be. We won’t pretend that thinking carefully always yields clear answers, but we believe it yields better practitioners: ones who can weigh competing values, sit with complexity, and make difficult calls with eyes wide open.

Dr. Eddie Jacobs and Dr. Bryony Insua-Summerhays

Ethics Corner Writers

A first preparation session often begins with a familiar scene: a new client sits down quoting Pollan or talking of “ego dissolution” and “connecting with the universe.” Their expectations arrive fully formed. You face a decision: open the frame or leave it intact, knowing it may shape the session. What people expect going in can shape – or constrain – what they experience. Expectation will be shaped either way. The only variable is whether you notice.

The Influence You Can’t Avoid

Psychotherapists have long grappled with the ethics of influence. Freud urged analysts to practise “evenly suspended attention”, a neutral openness intended to avoid steering patients toward particular insights.

This idea of neutrality-through-absence has a long reach, including to some psychedelic quarters: strip away the spiritual tchotchkes, the curated playlists, the warm furnishings, and what remains is neutral ground. Some early researchers fell into this trap: one study administered 800 μg of LSD to patients strapped to a hospital bed, explicitly omitting the music, imagery, and environmental supports other investigators were already seeing as therapeutic.

In trying to isolate the drug’s action, the researchers created a context of their own: clinical, austere, sterile. Unsurprisingly, results were no better than placebo. Such neglect of context, we now understand, might render a psychedelic experience clinically ineffective or potentially harmful. There is no neutral context. ‘Absence’ is simply a different kind of influence.

Expectation, Priming and Epistemic Trust

Many clients arrive already primed: uncertain, expectant, looking for orientation, giving small suggestions significant weight. Epistemic trust – the sense that someone can be relied on to offer information that is accurate, relevant and safe to take in – makes this even more central. Once established, it can act like a psychological lever. A client told that “resistance blocks the process” may later interpret ordinary difficulty as a problem – or a failure. Someone primed to expect “ego dissolution” may view depersonalisation as either breakthrough or crisis, depending on its framing.

Expectation shapes interpretation – that much is uncontroversial. Perhaps less obvious is how directly this can migrate into the acute experience. Psychiatrist Mortimer Hartman noted this decades ago, observing that Jungians practising psychedelic therapy elicited transcendental material from their patients, while Freudians evoked patients’ childhood memories. Recent work has reported similar. In a trial of psilocybin with CBT for smoking cessation, some participants reported acute imagery that mirrored that described in preparation – visions seemingly lifted straight from the manual. When epistemic trust is high, preparatory cues can become the architecture of experience. How far such framing effects extend to outcomes, rather than just experience content, remains genuinely unclear. But when epistemic trust is high and defences low, even modest influence may land with unexpected weight.

Steering the How, Not the What

Most protocols try to offer enough structure for safety without corralling the session. Hence the emphasis on process rather than content: stay curious, breathe through difficulty, let experience unfold. These orient people to how to meet experience rather than what to expect.

Yet process cues carry values too: “letting go” makes “holding on” problematic. “Trust the process” positions doubt as obstacle. These ideas have specific lineages – mindfulness, humanistic psychology, the countercultural history of psychedelic work. They may have value, but they are not neutral. Psychedelic sessions – like psychological life in accelerated form – often move through pockets of stuckness before they resolve. Framing fear or stuckness as part of this normal rhythm helps prevent clients from interpreting these states as threat or failure and keeps the frame broad.

Influence Without Agenda

Contemporary psychoanalytic thinking offers a different vision of neutrality: not blankness, but an active awareness of how timing, tone and phrasing shape the psychological field, with influence used to support openness, rather than steer toward a predetermined experience.

Balance is worth attending to. Too little structure leaves people uncontained; too much funnels them into a narrow corridor of expectation. Keeping influence process-focused preserves a middle ground, offering attitudes with which to meet experience rather than accounts of what may emerge. It also acknowledges that the frame stretches well beyond the dosing day: preparation and integration shape meaning just as much as anything that happens within the dosing session.

Some practitioners turn to the evidence base for reassurance. Yet here, the evidence is thin. Systematic reviews find that most psychedelic trials fail to report basic intervention details, or don’t share their manuals. And when those elements are reported, psychological interventions vary wildly. We simply don’t yet know which work better (or for whom), or even what approaches were actually delivered in published trials. This puts greater weight on practitioners’ own assumptions, making it all the more important to know what those assumptions are and how they enter the room.

A Question to Carry

Every clinician brings their own commitments into preparation: theoretical preferences, clinical instincts, personal values. Because they may feel obvious or benign, they are easier to overlook. In psychedelic work, where clients are unusually receptive, these unexamined assumptions can take on the force of explanation, as if they were simple facts about “how the medicine works”. This brings the ethical question into focus:

Are you preparing someone for the experience you expect, or helping them meet the experience they’re likely to have?

The difficulty isn’t influence itself, but influence that goes unnoticed. Preparation shapes the conditions in which the experience can unfold, be endured, and ultimately be made meaningful. The more transparent practitioners are about the values guiding that shaping, the more ethically grounded – and clinically useful – the work becomes.

Thank You for Reading

Our next Issue will be published in February. Join our free newsletter to make sure you receive it:

Thank you for reading our second Issue!

Josh Hardman and Alice Lineham

The Editors, The Psychedelic Practitioner