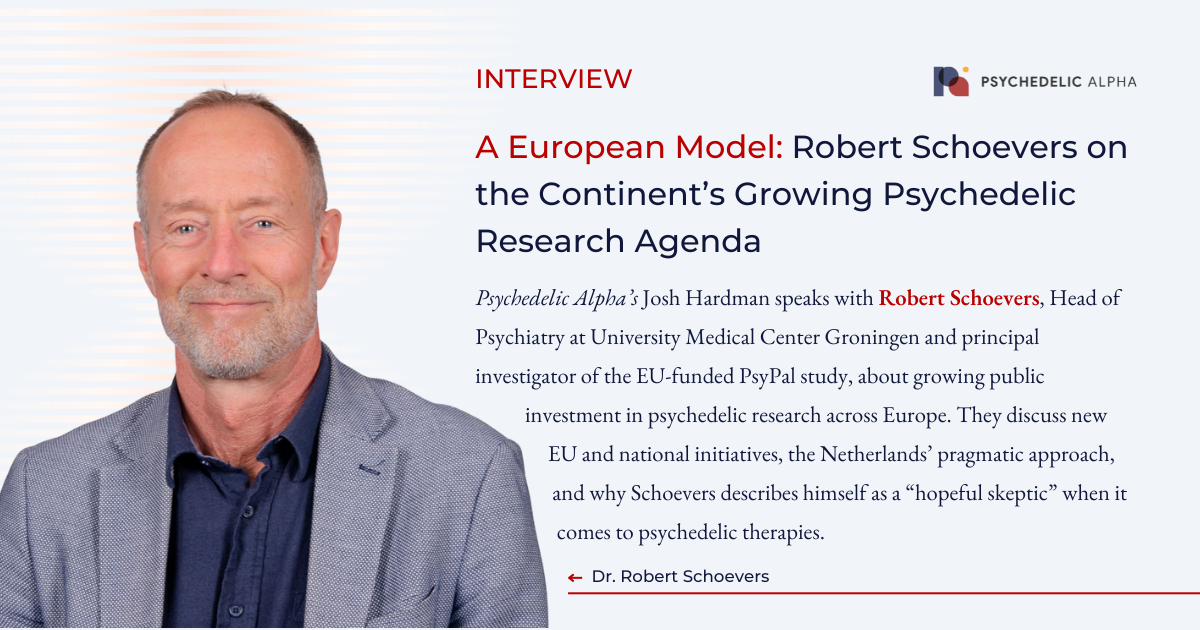

Few have done more to shape Europe’s modern psychedelic research landscape than Professor Robert Schoevers, a psychiatrist and epidemiologist who is, among other things, Head of the Department of Psychiatry at University Medical Center Groningen and principal investigator of PsyPal, a large, EU-funded study of psilocybin in patients with palliative care needs. As a lead architect of that project to securing support for a major EU-backed consortia, Schoevers has become a central figure in efforts to ground psychedelic research in rigorous, multidisciplinary frameworks.

In this conversation with Psychedelic Alpha’s Josh Hardman, Schoevers discusses the growing momentum for public funding for psychedelic research across the bloc. He reflects on the Netherlands’ relatively pragmatic approach to drugs and other issues that are more taboo elsewhere, his “hopeful skepticism” around psychedelic therapies, and why Europe must pursue its own models of care and protocols rather than waiting for the U.S. to set the agenda.

Josh Hardman, Psychedelic Alpha: Can you tell us about the various psychedelic research funding successes in Europe?

Robert Schoevers: Earlier this year, we learned that our proposal called ‘Integrate’ for Marie Skłodowska-Curie doctoral networks will be funded by the European Union (EU). We are very happy about that.

It consists of 16 PhD positions at different university organizations in the European Union and Switzerland, and they all circle around the central topic of psychedelics, but they go from neuroscience and clinical work to ethical, societal, and legal fields: a whole range of relevant domains around psychedelic treatment and acceptance and implementation, and how they interact.

I’ve always said that psychedelics sort of scream for such an interdisciplinary approach because their working mechanisms, clinical implementation and societal acceptance need to be evaluated in concert. The idea of a doctoral networks grant is that you provide a training environment for the next generation of researchers, clinicians, entrepreneurs, educators, and so on. We will also be able to create synergies with our other psychedelic research project funded by Horizon Europe, PsyPal, a study on the efficacy and longer-term outcomes of psilocybin-assisted therapy for palliative care patients with depression. This will generate data that the PhD students can work with.

The official communication from the EU is available online. We will start hiring PhD students by the end of the year, and the official project start will be in March 2026.

Josh Hardman: That sounds great. I understand you also secured some funding from the Netherlands Ministry of Health?

Robert Schoevers: Together with Joost Breeksema and other colleagues, we wrote an overview of the field of psychedelic treatments and the potential relevance for medicine for ZONMW (Netherlands Organisation for Health Research & Development). In that, we outlined the promise, the knowledge gaps, the challenges, and so on, and we proposed to set up a large research program where you do a whole range of different studies for various indications using basically the same—as much as possible—measurements, instruments, timing, and so on; so that you can not only look at primary efficacy, but also compare non-drug factors like the role of psychotherapy and also look at possible transdiagnostic aspects of these treatments.

We tried to get money for a very ambitious national program from Netherlands Growth Fund, which was an initiative from the Ministry of Economic Affairs to boost growth. But then we got this fantastic new government, which by the way has fallen twice already now, and the first thing they did was take out the billions that were reserved for innovation and sustainability.

But the Ministry of Health still thought that this was a relevant topic, so that’s why they put out this call, which is sort of a shrunken version of the grand idea that we had. But it is a good start and we are very happy that it allows us to make important steps with a national consortium.

We are working very hard on a detailed proposal, in the sense that we propose that we perform a clinical trial involving one psychedelic for one category of treatment resistant patients, being mindful of the current concerns regarding blinding, expectancy and the role or psychotherapy. In the next step the funding body will put out a new call so everybody can apply to carry it out for which we as a consortium of specialized mental health providers will certainly apply.

Within psychiatry in the Netherlands I think people are really interested in this development, for a good reason. It is one of the first times in our field in many years that there is really the possibility of having something innovative that may catalyze treatments like psychotherapies that we that we now use. So I think all of that is quite good news.

Josh Hardman: Why do you think the Dutch state is so open to this research?

Robert Schoevers: Dutch culture and politics have been quite pragmatic on these kinds of topics. It’s also the case with addiction care: We were one of the first to decriminalize heroin addiction and we had all these programs like clean syringes for free, no questions asked methadone programs, and so on. We saw much less complications, much less severe addiction than in countries where the political and legal approach was much more strict towards criminalizing users. In the Netherlands we also have policies on euthanasia that are less politicised than in some other parts of the world.

So I think in that sense it fits.

Hardman: So you are very excited about psychedelics in medicine?

Schoevers: In my group, we are cautious in claiming all kinds of successes. I consider myself a hopeful skeptic. I really hope it works, especially for our most severely ill patients for whom other treatments don’t work. It’s also mechanistically very interesting. So, if they work, what is the mechanism of action? And is that purely psychological, how does it relate to findings on neuroplasticity and the connectivity of brain networks? In addition to that, we learnt a lot from our participants, from patients and families. Qualitative studies at this point provide an important complement to quantitative research as you get much closer to patient experience, the role of therapists and more. It’s interesting from many sides but I think we shouldn’t oversell the potential of psychedelics for mental disorders at this point in time.

Hardman: What other areas of research do you think that that either the Netherlands or Europe is well positioned to conduct? As we have discussed before, most of this work has happened in the US in terms of dollars donated or spent on research, but why is it important to do this work in Europe?

Robert Schoevers: Well, I think because, just like in the US, we have hundreds of thousands of patients with treatment-resistant mental conditions. And if we wait for the big companies to roll out from the US, it will take 10, 15 years.

It could also be interesting to see if we could develop other models of care. I know that sounds quite idealistic, but could we also collaborate with parties who are not only in it for profit, but also for other values?

And third, I think we still need a lot of proof of efficacy, because of the likelihood of placebo effect or specific aspects playing a large role and sampling bias, which is huge still. So, we really have serious hurdles to pass before we can say this is evidence-based, and also before we can safely apply it to our most affected patients. So many trials up till now have selected people with relatively higher education who had sort of actively sought these kind of treatments, who may have had an earlier personal experience, and so on. My garden variety patient with treatment-resistant depression is a 50 year old lady who is in her sixth episode, who has relatively lower education, who may not be able to verbalize so well everything that happens to her in a session, and she has had severe negative experiences in her early childhood, so she doesn’t automatically feel safe when she has to let go.

I think we don’t address that enough in the field, to be able to say that this is a credible next step in the treatment of patients who are most in need.

Josh Hardman: I think Europe’s well placed to do the accessibility or scalability-focused studies, like group sessions or peer support. I know you’re doing some of that in PsyPal, could you talk about that?

Robert Schoevers: That is another unknown at this point. People with severe mental conditions, do they really remit for a much longer time and does that balance the investment in treatment hours and medication? There’s hardly any studies that may answer that question and what is needed to keep people in remission, and can we do that in a in a way that is feasible, that is that is not too costly?

We have a one year follow up in PsyPal where we have monthly meetings with facilitators, and we do a lot of qualitative research, and we note what kind of other care people seek during that year. So we are not going to say we don’t allow you to do certain things, but we offer them this monthly support, and they can also interact through an online environment in between. We just want to naturalistically learn what is helpful for them to maintain their psychological state as good as possible. I think we will learn a lot from that.