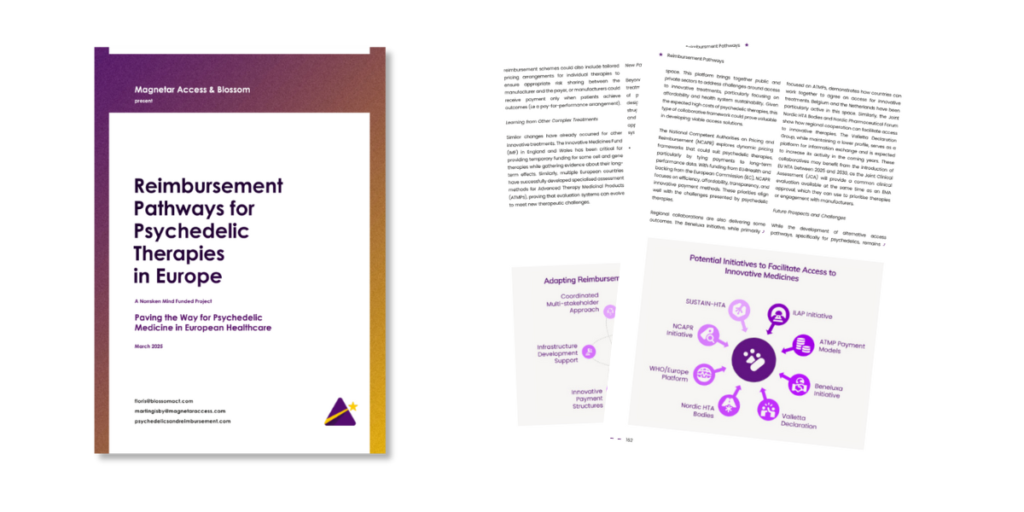

Today, a report focused on reimbursement pathways for psychedelic therapies in Europe was published.

Authored by Magnetar Access and Blossom, the 200-odd page document aims to provide actionable insights for drug developers, payors, regulators, and other key stakeholders, and is complemented by a closer analysis of key markets such as the UK and Germany.

The report is available to view via a dedicated website.

Psychedelic Alpha Editor Josh Hardman was pleased to act as a collaborator on the project, which included penning the below comment piece…

Beyond Guinea Pigs: Ensuring Access to Psychedelic Therapies for Europeans

By Josh Hardman

With several pivotal programs currently underway in the United States, we could see the first psychedelic therapies approved by a regulator within the next few years. But, the timeline for approval and market access in Europe remains uncertain, with the U.S. being the primary focus for psychedelic drug developers.

While any approval, anywhere in the world, will rightly be viewed as a momentous milestone for the field, it will only be the starting line for making these therapies available to those who might benefit most; especially in Europe, where this report focuses.

That’s why psychedelic drug developers, policymakers, payors, regulators, healthcare practitioners and systems, patient advocacy groups, and other stakeholders must begin the work of scoping out these unique medicines’ integration into the complex systems of Europe today.

Perhaps most foundationally, psychedelic drug development programs must produce data that allows health technology assessment (HTA) bodies to compare these relatively expensive and complex interventions to the standard of care. Such programs should give HTAs confidence in modelling costs and benefits over the medium term by providing reliable inputs to such models, including elements such as data on durability. While European HTAs have similarities to one another, drug developers might be wise to design programs and data packets with specific markets and assessors in mind.

They needn’t go it alone, however, with evidence suggesting that early engagement with HTAs can lead to faster review and market access timelines. Both Maignen and Kusel (2020) and Wang et al. (2024) show that sponsors that used the UK’s NICE scientific advice pathway shaved months off their eventual appraisal processes.

Some issues are outside of the control of drug developers, however. Those include a general lack of funding for behavioural and mental healthcare interventions versus other fields of medicine like oncology in many of the EU member states and the UK; HTA models that often valorise costs and benefits narrowly at the healthcare level, as opposed to recognising those realised at the societal level; and, in many cases, underfunded healthcare systems that have stretched budgets and resourcing shortfalls. Take the UK, for example, where I live: There is not exactly a surplus of specialised treatment environments or trained professionals. That raises all sorts of questions around service readiness or the likelihood of equitable access to psychedelic therapies, if approved—the high upfront costs and logistical burdens of psychedelic therapies would need to be rationalised against the operational realities of our National Health Service.

While drug developers must be attentive to developing interventions that can ultimately plug into existing healthcare systems and produce relevant data to support their reimbursement, there is room for innovation and implementation-readiness activity to be carried out by other stakeholders. For example, government-funded studies could support the exploration of alternative delivery paradigms for psychedelic therapies to increase scalability and reduce resource intensity. Those might include things like group or simultaneous dosing and/or preparation/integration sessions.

Governments and other non-industry research priorities might be carried out in the post-approval context, too. Those could include pharmacoeconomic or head-to-head studies that seek to ascertain the value of one therapy over another. In the U.S., for example, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is funding a comparative effectiveness study of esketamine (Spravato) vs. IV racemic ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Such studies might be of particular relevance to European countries that have taxpayer-funded healthcare systems, as it is in the interest of the public purse to determine the relative value of interventions. While it might be some time before we see generic psychedelics come to market in Europe, owing to patents and other exclusivity periods, these studies could at least put any approved therapies head-to-head with existing treatment options.

While “multi-stakeholder approach” often strikes me as an empty term, here is a case where it is surely appropriate! As such, I am pleased to have made a small contribution to this report, which aims to provide various stakeholders with insights into the state of play of psychedelics and reimbursement pathways in Europe, but also what we hope is actionable advice, especially that contained in Section 8.

To be sure, none of this is straightforward. Perhaps that’s why many psychedelic drug developers are looking to side-step the complicating factors of long-duration dosing sessions and accompanying psychotherapy by moving toward shorter-duration psychedelic-based medicines that are administered in increasingly hands-off protocols. In other cases, drug developers are aiming to engineer out the trip entirely, though this report does not look substantially at this development.

But, even shorter-acting psychedelics delivered within a very slim psychological support protocol might face challenges in Europe. Look at Spravato, for example. Despite the backing of a company worth $375+ billion, the product’s availability and reimbursement across the bloc and in the UK remains uneven, as is explored in Section 2.2.2. And yet, Spravato is still a blockbuster drug thanks to strong sales in the U.S., which remains the key market of focus for most developers of new drugs.

The challenge is real, then, but nowhere near that which Europe and its citizens face when it comes to mental and behavioural health. And as I said in Brussels in late 2023, I fear that if we don’t focus on ensuring access to innovative mental health treatments in Europe during their development, we risk Europeans becoming guinea pigs. What I meant is that we could see a scenario where Europeans serve as test subjects in the early- and mid-stage clinical trials of such interventions—as they have done in the psychedelics realm—but do not realise the benefits of such research through access to innovative therapies after they are approved in jurisdictions like the U.S.

But through a proactive approach, the genuine engagement of appropriate stakeholders, and perhaps the leveraging of innovative risk-sharing programs and member states, psychedelic therapies just might ‘work’ for Europeans. ∎