The UK’s seventh biennial international conference on psychedelic consciousness welcomed researchers, clinicians and delegates to the University of Exeter from 17–19 April. In this first instalment, we dive into:

- ketamine’s path into public healthcare,

- efficient and ethical trial designs,

- overlooked risks in the underground psychedelic scene,

- and, whether new modalities of care can avoid repeating psychiatry’s historic mistakes.

***

Words by Charles Bliss for Psychedelic Alpha.

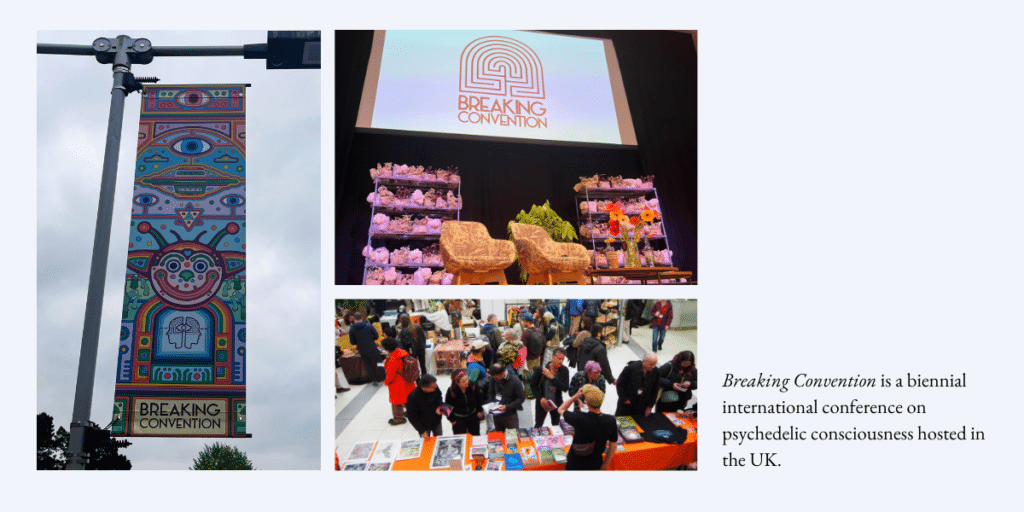

On a bright breezy day in April, the University of Exeter’s Streatham Campus was transformed into a labyrinthine tangle of mycelial sculptures, pop-up book shops, tarot readers, virtual reality headsets, Day-Glo artworks, DJ turntables, Indigenous jewellery, health supplements, (zero THC) ganja iced tea and posters advertising an interactive art installation reading: “You too can become an amorphous blob.”

Inside lecture halls renamed in honour of scientific luminaries like Albert Hofmann, Maria Sabina and Alexander Shulgin, more than 200 speakers convened to explore the evolving frontier where psychedelics meet medicine, psychology, sociology, anthropology, law, politics and art.

Breaking Convention is a multi-disciplinary academic conference showcasing the latest research and insights into drug science. This year, the three-day event operated without corporate sponsorship, relying solely on ticket sales and drawing 1,400 delegates.

“Breaking Convention is not only my favourite psychedelic conference but the only one I still go to,” said Erik Davis, event speaker and author of Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium. “I like the underground energy it still carries, married as always to outlandish rigour, a wide imagination, and a commitment to the shrinking non-corporate dimension of existence.”

What follows is a dispatch from the first two days inside Breaking Convention 2025—a glimpse into the conversations shaping the future of psychedelics.

Scaling Ketamine: The Trojan Horse Tranquiliser

We have to try to fit into a system that might not really want us.

Celia Morgan

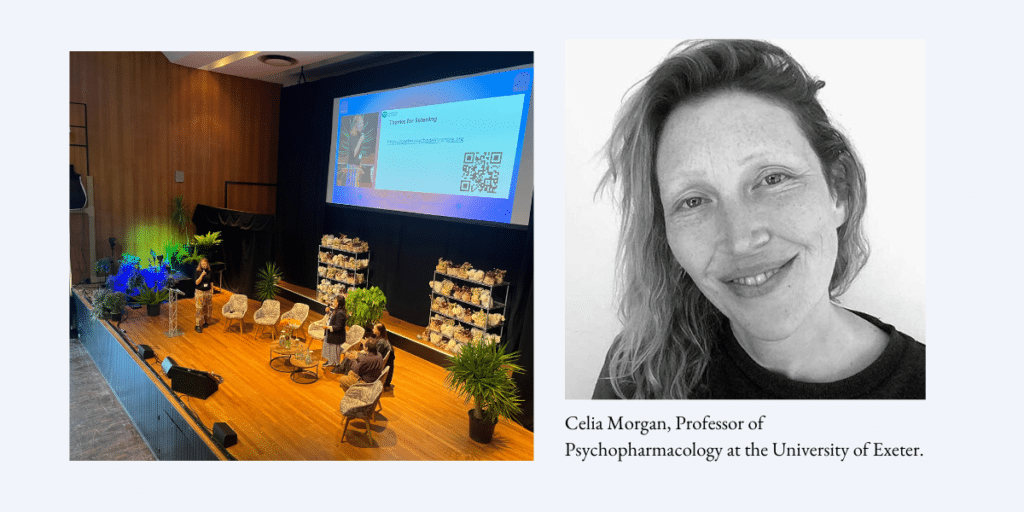

On Thursday, 17 April, the afternoon programme at Hofmann Hall focused on potential strategies for integrating psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) into existing healthcare systems.

Celia Morgan, Professor of Psychopharmacology at the University of Exeter, curated the session, which focused on equitable access, community building and mainstreaming psychedelic treatments in the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) protocols and beyond.

Morgan, who has a PhD in Psychology and has spent more than 25 years in drug research, has led the world’s largest ever studies of ketamine combined with talking therapy, with a focus on reducing alcohol relapse. Her Awakn Life Sciences trial found that participants with alcohol use disorder who received ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) went from drinking daily to remaining sober 86% of the time. (A Phase III trial of KAP has so far recruited 280 people across eight sites, and a pilot trial for treatment-resistant depression is also underway.)

In her talk, Morgan argued that KAP—despite its challenges—could help establish the necessary infrastructure for other psychedelic therapies in public healthcare, potentially paving the way for broader systemic change.

She noted that, although ketamine has garnered increasing interest, access remains largely restricted to a privileged minority—those who can afford out-of-pocket payments at private clinics. She argued that integrating psychedelic therapies like KAP into public health systems offers a way to democratise access and reach a broader, more diverse population.

Morgan discussed the necessity of finding a “frictionless” way to mainstream psychedelics via the UK’s healthcare system. She emphasised that, while the NHS is often slow to change, it still provides a trusted and structured platform that could make psychedelic therapies more accessible—if navigated properly.

She proposed that ketamine represents a “Trojan horse tranquiliser” that could infiltrate the system from the inside. If KAP could be normalised like “just another antidepressant”, Morgan argued, further psychedelic modalities might be able to sneak into NHS mental health provisions following the same model.

Morgan described ketamine as both “a wrong’un and a right’un”. On the negative side, she pointed to its potential for abuse, as well as its associated health risks including bladder and kidney damage. She also alluded to the high-profile death of actor Matthew Perry, as well as the erratic behaviour of Elon Musk, who has admitted to taking prescription ketamine, which Morgan said have been detrimental to the drug’s reputation. Further problems concern a 650% rise in ketamine-related deaths in the UK since 2015, prompting Policing Minister Diana Johnson to formally request that the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) re-evaluate its legal status with a view to placing ketamine in Class A, the UK’s most severely penalised drug classification.

Morgan said that ketamine’s “most attractive quality” when compared with other psychedelic and psychedelic-adjacent drugs is its current scheduling status. Ketamine is already a licensed drug, primarily administered for anesthesia, which ensures regulatory hurdles are easier to overcome compared with unlicensed psychedelics in both Schedule I and Class A.

She also emphasised the unique properties of the drug which make it suited to the existing healthcare system. One of ketamine’s major advantages, according to Morgan, is its short duration of action compared to other psychedelics, making it more cost-effective and easier to manage in clinical settings.

She spoke about the practical realities of working within a public health system: costs must be tightly managed from the beginning, because an expensive model will never be widely adopted. This also influences decisions about therapy structures, staff training and session formats.

Morgan argued that, because the “system as a whole is risk-averse”, it is important to ensure that “the right people buy the horse”. By this she meant institutions such as the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). “We have to try to fit into a system that might not really want us,” she said.

Morgan discussed how the drug’s dissociative, anxiolytic and ego-dissolving effects could allow patients to create emotional distance from trauma, difficult memories or psychological pain. She noted that, although ketamine produces altered states, healthcare systems traditionally categorise these as side effects, not therapeutic processes—something that needed to shift if ketamine therapy was to be properly understood and integrated. She stressed that building a “safe container” around the drug experience would be essential, including peer support and integration groups.

She also underscored the importance of therapist understanding. Many practitioners within NHS systems lack personal or professional experience with psychedelic states, Morgan said, so part of the work will involve training therapists to develop a supportive “cosmology” to navigate and guide patients.

Morgan ended by reflecting that although systemic change is slow and difficult, bringing KAP and PAT into the NHS might not just improve individual patient outcomes but could, over time, subtly shift mental healthcare systems themselves toward more holistic, human-centred approaches. (A full-length interview with Celia Morgan will appear in Psychedelic Alpha in the coming weeks.)

Further talks on Thursday included Anne Katrin Schlag, Head of Research at Drug Science, on the challenges and opportunities of psychedelic medicine in the “real world” and Maria Papaspyrou and Tim Read from the Institute of Psychedelic Therapy on the role of co-therapy in PAT.

Rick Doblin also addressed the crowd with updates on the future direction of MDMA-assisted therapy, and repeated his ambition for “net-zero trauma” by 2070. He pointed to a number of current and future MAPS initiatives for the treatment of PTSD among citizens of war-torn nations including Somaliland, Ukraine, Israel and Palestine.

A Delicate Balance

Understanding the importance of a non-clinical space that feels relaxing and welcoming and helps put you at ease is important, obviously, for patients undergoing psychedelic-assisted therapy, where they will be in that vulnerable, suggestive state

Henry Fisher

At the Shulgin Salon on Friday, 18 April, Clerkenwell Health’s Chief Scientific Officer Henry Fisher discussed the key lessons he and his team have learned while building a commercially-focused Contract Research Organisation (CRO) and clinical site network specialising in psychedelic trials.

His talk, ‘Balancing Scientific Integrity, Business Viability and Patient Outcomes’, emphasised that the psychedelic sector must learn from established clinical development practices while maintaining the distinctive insights psychedelics bring, particularly around patient care and experience.

In an interview with Psychedelic Alpha, Fisher said the psychedelic sector must radically expand its understanding of set and setting. In his view, set and setting are not limited to the therapy room or the dosing session, but must be extended “to the whole clinical trial experience” to include every patient interaction.

“I think [this] is something that is not done sufficiently within the trials that are run in this space at the moment,” he told us.

By treating the entire clinical trial journey as part of the set and setting, Fisher said, trial organisers can foster a stronger sense of safety and connection for participants, leading to better retention rates, higher compliance and ultimately stronger data. This approach is valuable not just for psychedelic research but could also improve clinical development more broadly, he suggested.

“Understanding the importance of a non-clinical space that feels relaxing and welcoming and helps put you at ease is important, obviously, for patients undergoing psychedelic-assisted therapy, where they will be in that vulnerable, suggestive state,” Fisher said. “But also it’s incredibly relevant for someone [in the] neurodegeneration population, for example, where there might be an increased risk of agitation or disorientation.”

Fisher stressed the importance of designing clinical trials with efficiency in mind. Most trials at Clerkenwell Health are structured with adaptive designs, which he said are common in broader clinical research but are rare in academic psychedelic studies. Adaptive trials allow different phases of a study to evolve based on interim results, reducing regulatory delays, administrative burden and overall costs. Though adding an adaptive component can introduce more complexity, Fisher argued that it ultimately leads to clearer data and faster results, something the psychedelic field needs if it is to scale responsibly.

He also spoke about the challenges of the psychotherapy component in psychedelic trials. Recent feedback from regulators, particularly the FDA’s response to Lykos Therapeutics’ New Drug Application (NDA) for MDMA-assisted therapy in PTSD, might point to the risks of offering therapies that are too loosely defined, Fisher suggested.

“The therapy manual left a lot up to interpretation and flexibility,” he said. “Ultimately, that was an issue for the FDA. And so what we try to do when we design our trials and deliver them is [to] find ways to dial down that room for interpretation or error.”

Fisher said that Clerkenwell Health uses a “monitoring software” that assesses fidelity to manuals, helping ensure therapists remain consistent, while also reliably analysing the outcomes of the drug component and minimising risks of accidental unblinding.

Fisher noted that, while standardisation is necessary, trials must also preserve enough flexibility for therapists to deliver meaningful support to participants. He emphasised that clinical trial processes, like collecting blood pressure readings during a session, must be handled carefully to avoid disrupting therapy and undermining patient trust.

“They’re all essential components of the design of the trial,” Fisher told us. “[But] if we know that that’s going to affect things, can we reduce that burden? Not only from the patient perspective—which I think is usually how that burden is visualised—but how can we reduce that for the therapist to allow them to do their job effectively?”

“A lot of those physical safety measures need to be collected at certain times. How can we ensure that the staff doing that know to do so in an understanding way? And that’s where, again, it comes down to set and setting [as] the entire clinical trial experience. It’s not just the room they’re in and the way the therapist is delivering it. It’s also how that research nurse goes in and explains that they’re going to be taking their blood pressure in the middle of a dosing experience, for example.”

On the regulatory front, Fisher highlighted that the UK has recently improved its clinical trial approval timelines, becoming one of the fastest regulators in Europe. He also mentioned that the country benefits from a deep pool of psychedelic research expertise at universities like King’s College London and Imperial College London, as well as a “well-established network” of clinical trial sites.

“It’s really having that spread of sites that can deliver and recruit at speed and deliver high-quality data that will be crucial [for] demonstrating that the UK can stand up there,” he told Psychedelic Alpha.

He said that one “unique selling point” of the UK market is the potential for mainstreaming psychedelics via the national healthcare system. Clerkenwell Health is leveraging this environment by building partnerships with NHS Foundation Trusts, aiming to integrate psychedelic research into public mental healthcare. He described how the company’s new site, developed with an NHS Trust, will combine the agility of a private CRO with insights from real-world clinical settings. This hybrid model, he suggested, could create a “blueprint” for how psychedelic treatments might eventually be delivered at scale.

However, he pointed out that challenges remain, particularly around the UK’s Home Office licensing process for controlled substances, which can feel like a “black box”. Current rules mean companies must wait until after MHRA approval before even beginning the licensing process, causing an “unnecessary lag” of up to three months. These delays, he warned, are significant enough to deter some companies from operating in the UK altogether, and he called for reforms that would allow both approval processes to run concurrently. (As we reported in February, GH Research CEO Velichka Valcheva told us that the company did not enrol trial participants in the UK due to “significant delays” around “drug licenses and bureaucracy”.)

He also argued that, as psychedelic drugs gain regulatory approval, attention must increasingly shift toward researching and optimising the psychotherapy component of treatment.

“It’s really important for the companies that are developing these drugs and designing clinical trials and managing them—[and] the CROs as well—to not lose sight of the patients themselves,” Fisher said. “They’re delivering drugs that create a psychedelic experience which, regardless of its clinical effect, although that is honestly fundamental to how profound these experiences are… is life changing, and is something that I think can easily be overlooked when companies are in the finer details of figuring out specifics of inclusion and exclusion criteria or what a certain outcome measure should be.”

Applying commercial clinical trial methods to this next phase of research, he argued, will be crucial to refining the full potential of psychedelic therapies in healthcare.

Confronting the Shadows

I don't think journalists necessarily have to have tripped to write about it, in the same way that I don't think psychiatrists need to have tried every drug on their shelf

Mattha Busby

Friday’s programme on the Sabina Stage played host to a deep dive into the underbelly of psychedelic healing.

Mattha Busby, a journalist who has covered psychedelics for publications including The Guardian, Rolling Stone and VICE, explained that while he remained sympathetic to the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, he has also uncovered serious problems in the field.

Busby began by describing how mainstream psychedelics had become, citing examples like American football celebrations referencing ayahuasca. However, he noted that commercialisation has quickly taken over, sometimes in troubling ways.

He shared an investigation he conducted into a hotel in Tulum, Mexico where Bufo alvarius secretions containing 5-MeO-DMT, were being administered with little preparation, guidance or aftercare. He described witnessing chaotic ceremonies where people, improperly prepared, experienced adverse psychological fallout.

He then recounted his personal experience at a high-end Ibogaine clinic in Cancun. Although his own treatment was positive, he later learned that another participant had died at the same treatment centre. This led Busby to question the transparency and safety practices at facilities marketing themselves as leaders in the psychedelic healing space. He also spoke about visiting a separate Iboga retreat in Costa Rica, where another death later occurred, again raising concerns about how little oversight existed in the nascent industry.

In an interview with Psychedelic Alpha, Busby said that experimenting with the drug firsthand at these clinics gave him “greater insight into the nature of the experience”.

“I don’t think journalists necessarily have to have tripped to write about it,” Busby told us, “in the same way that I don’t think psychiatrists need to have tried every drug on their shelf… But there’s obviously a risk for bias as well.”

Busby, who is a recipient of the Ferris–UC Berkeley Psychedelic Journalism Fellowship, said best-selling books like How to Change Your Mind, in which Michael Pollan used an immersive approach to report on the psychedelic underground, might not capture the full complexity of the scene.

“Michael Pollan came into it as a fully-fledged adult—a professional, famous journalist—and it seems like he got the very best in terms of the facilitators that he got,” Busby said. “And so I guess it’s more likely that he [would] probably have a good experience, right? And he reported it as such.”

“But I’ve been around and about doing $75 ceremonies in Mexico and I’ve encountered the dark side, too.”

Busby said he hopes to see further regulation for psychedelic services similar to the models adopted in Oregon and Colorado, which he feels could “drive up standards”—but only if it remains affordable.

“If it’s not, then it won’t really matter, because everyone else will just go underground,” Busby told us.

In his talk Busby warned that, as psychedelic retreats have proliferated, many centres are using celebrity endorsements, social media ads and slick marketing to draw in vulnerable people—often without adequate safety measures. He exposed cases where retreat founders had criminal backgrounds or where fatalities were covered up.

Busby also discussed how some shamans practised brujería (witchcraft), deliberately inflicting spiritual harm on participants. Busby referred to anthropological research showing that shamanism has historically involved rivalry, sorcery and power struggles. He argued that modern ‘psychedelic renaissance’ narratives focusing only on benevolence and healing often ignore these long-standing dynamics. He cited studies and historical texts revealing that shamans used psychedelics not only to cure, but also to curse.

He concluded by saying that while increased access to psychedelics was, overall, positive, the community needed to be more discerning. He stressed that failing to acknowledge the complexities and dangers of powerful psychedelics risked repeating mistakes from the past and putting people in danger.

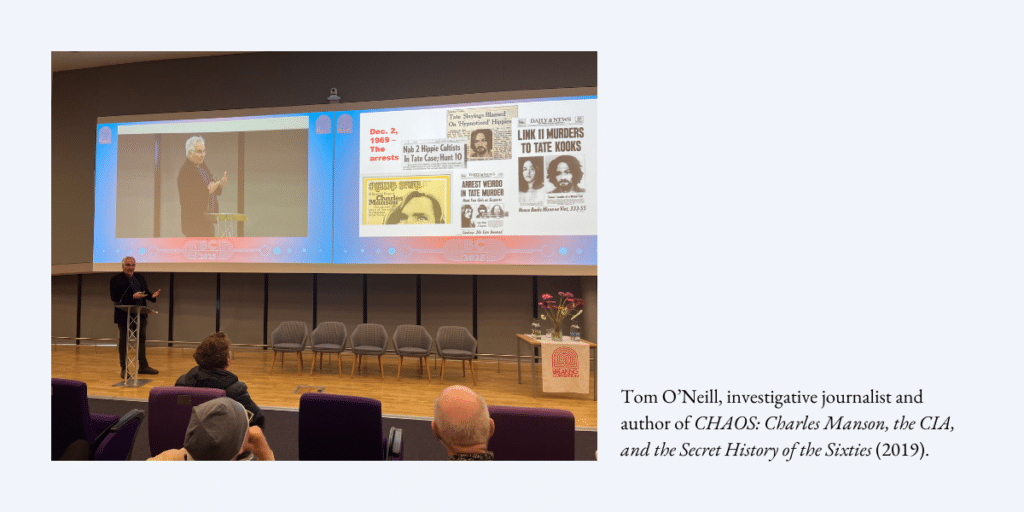

One particularly notorious lesson from history about the perils of psychedelics was the subject of a lecture by journalist Tom O’Neill on Friday afternoon. O’Neill shared what he had learned from a twenty-year investigation into the Tate-LaBianca murders committed by the Manson Family in 1969—and the role that psychoactive substances played in the tragedy.

O’Neill, the author of CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties, gave a wide-ranging talk on the unsettling intersections between government agencies, drug research and the Family’s brutal ritualistic killings.

He framed his talk around the idea that government scientists who crossed paths with Manson at the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic after his 1967 prison release may have influenced the course of his life—and ultimately, the infamous murders two years later.

He suggested that Manson could have been shaped by hidden federal programs and experimental research on drug use and behaviour modification, including the CIA’s Operation Chaos and the FBI’s COINTELPRO programmes, which were actively undermining leftist movements through infiltration and psychological operations. Meanwhile MKUltra, the CIA’s infamous mind-control program, had been secretly dosing citizens with drugs like LSD in experiments aimed at creating “Manchurian candidates”—assassins who would kill on command with no memory of being programmed.

O’Neill acknowledged, however, that while his first book uncovered significant circumstantial evidence, it could not definitively connect all the dots. That uncertainty has driven him to continue his investigation in a second book, exploring whether Manson’s evolution into a cult leader capable of remote-control murder was coincidental—or whether it had been the result of hidden scientific experiments and covert government programs operating around him.

A long, hard trip into the future

Every week, studies are published proving that things like nature, singing, dance, exercise and community make us happier, framing these things as prescriptions for ills, rather than the cornerstone characteristics of healthy lifestyles that prevent those ills.

Rose Cartwright

During an evening event at Hofmann Hall, memoirist and screenwriter Rose Cartwright interrogated whether psychedelic therapy can avoid repeating psychiatry’s historic mistakes.

Cartwright, author of The Maps We Carry, challenged the dominant narratives in both mainstream mental healthcare and the emerging psychedelic field. She argued that, while the psychedelic movement presents itself as “progressive”, it still fails to engage deeply with the systemic, cultural and social roots of psychological suffering.

Speaking from lived experience, Cartwright reflected on two decades of engagement with mental health treatments—therapy, antidepressants, alternative approaches—and the psychiatric system’s persistent failure to address the deeper causes of distress. She emphasised that patient perspectives are too often subordinated to professional authority, and that people experiencing mental health issues are often the true experts on their own “inner lives”.

Cartwright’s critique extended to the medical model and the reductionist use of diagnoses. She described how her OCD diagnosis once offered her identity and meaning, only to later discover that such diagnoses were not rooted in biological fact, but were the product of politics within psychiatry. She recalled how, while conducting research at the Wellcome Library, she discovered the story behind how the psychiatric categories in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) originated.

“During these meetings, a team of up to 15 psychiatrists would get together to decide what diagnosis would be and would not be included,” Cartwright said. “How did they decide? Not with biological evidence from brain scans or blood tests and so on, since no evidence existed, but by arguing amongst themselves.”

Cartwright recounted that during morning meetings the psychiatrists would turn up “raring to go”, participating in heated arguments before voting on diagnostic and inclusion criteria which, she said, were “biased by desire for prestige and financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry”.

But after a heavy lunch of deli sandwiches and pickles, the professionals were “much less animated” and “less motivated to scrutinise or argue”, she said.

“This means that the diagnoses that went on to influence the treatment of millions of people were potentially conceived in a food coma—the product of an unserious, unscientific, cavalier and financially incentivised process,” Cartwright said. “Does this sound like the kind of framework on which we should build psychedelic research?”

She went on to warn of similar dynamics (minus the pastrami) playing out in the psychedelic space, where diagnoses are again being used to sort people into treatment pathways—often in ways that obscure rather than clarify.

She described her shift in perspective from seeing mental illness as a biological malfunction to understanding it as the product of relational, social and political contexts. She was critical of a system that pathologises individuals while ignoring the environments and structures that generate distress.

Cartwright then invoked a sentiment from Burkinabé writer Malidoma Patrice Somé: “The modern world is on a long, hard trip into the future in search of the values of the past.”

“What we already know in our bones as traditional knowledge is subjugated to scientific authority,” Cartwright said. “Every week, studies are published proving that things like nature, singing, dance, exercise and community make us happier, framing these things as prescriptions for ills, rather than the cornerstone characteristics of healthy lifestyles that prevent those ills.”

Throughout the talk, Cartwright returned to the healing potential of community—not just in terms of people, but also in connection with place, culture and the natural world. Cartwright quoted psychiatrist Allen Frances, who said: “It doesn’t require rocket science or new research. We have known for 50 years how to provide good care for severe mental illness. There is nothing mysterious or complicated about it. Decent housing. Easily accessible treatment. Social clubs. Vocational rehab. Positive regard, respect and empathy. Family support.”

Echoing the cautionary tales of Mattha Busby and Tom O’Neill’s talks earlier in the day, Cartwright also expressed concern about guru-like figures in psychedelic communities who impose rigid frameworks on vulnerable people, mirroring the same dynamics she had witnessed in psychiatry.

Despite her criticisms, Cartwright did not dismiss the value of psychiatry or PAT entirely. Instead, she called for intellectual humility, epistemic openness and a refusal to mistake any single framework for objective truth. She urged the audience to keep multiple models on the table, allowing them to balance and check one another. ∎

There’s more to come from Saturday’s events at Breaking Convention 2025 in Part 2.