Psychedelic Sector News

REMS Patents: the Next Frontier in the Psychedelics Patent Skirmish?

As psychedelic therapies inch closer to potential approvals, it’s prudent to begin thinking about what strings may be attached to such approvals.

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) often mandates the provision of Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) programs alongside (or, after) the approval of a potentially dangerous therapeutic, in an attempt to ensure the benefits of the product outweigh its risks.

As biopharmaceutical companies seem to have an unfettered appetite for finding ways to extend the patent lifecycle of their products, many have looked towards patenting REMS as a way of shoring-up time-limited monopolies and staving off generic competition.

Given that this unfettered appetite for IP appears to be pervasive in the psychedelics space, too, it’s likely that we will see a similar dynamic unfurl in the coming years.

And so, at least a basic understanding of REMS, and the potential patentability of REMS programs, is well advised.

Below, we first provide a brief overview of REMS, before illustrating how they might collide with patents.

Note that the below is just that: a brief overview. It neglects to cover important intersections between REMS and other relevant legal and regulatory frameworks such as the Hatch-Waxman Act, Orange Book listings, and more; it also focuses on the U.S., but note that similar schemes exist in other jurisdictions, such as Risk Management Plans (RMPs) in Canada, and additional risk management measures (aRMMs) in the EU.

REMS: A Primer

When approving drugs that it deems to be potentially dangerous, the FDA often mandates the provision of Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) programs. The purpose is to ensure, as far as possible, that the benefits of the product outweigh its risks.

This program was institutionalised in 2007, with Congress passing several amendments that conferred the authority to require REMS from manufacturers where the FDA deems them necessary. The program replaced Risk Minimization Action Plans (RiskMAPs), a voluntary system introduced in 2005.

REMS can be mandated following the submission of a New Drug Application (NDA), which is submitted post-Phase III, or at any time post-approval. They can also be removed if they are deemed to become unnecessary, and therefore only c.6% of FDA-approved brand name drugs are thought to have REMS attached to their marketing.

The FDA considers six factors when determining whether a REMS is necessary:

- the seriousness of potential adverse events related to the drug and the background incidence of such events in the target population;

- the expected benefit of the drug to the target population;

- the seriousness of the disease or condition to be treated;

- whether the drug is a new molecular entity;

- the duration of treatment with the drug;

- the estimated size of population likely to use the drug.

In practical terms, REMS can be as simple as the paper insert you find in many pharmaceutical products which outline pertinent information about the drug and its safe usage. It could also take the form of a detailed communication plan, in which the drug’s manufacturer explains how it will disseminate information on the appropriate use of the product (and its risks) to relevant stakeholders including prescribers, pharmacists and the target patient population.

The majority of REMS also include Elements to Assure Safe Use (ETASU), which can codify a prerequisite level of training or accreditation for prescribing or administering the drug. It may also mandate, for example, screening for specific comorbidities or other patient characteristics prior to the administration of the drug, and/or monitoring after the fact.

The REMS program is to be designed by the drug manufacturer and reviewed by the FDA, who ultimately decide whether to approve the proposal.

Previously, the FDA required a generic manufacturer to use a “single, shared system” (SSS) REMS with the brand manufacturer, unless the generic manufacturer applied for and received a waiver. Grounds for a waiver were that the burdens of forming a SSS outweighed the benefits, and that the generic manufacturer was unable to obtain a license to REMS patents.

This system created an opportunity for brand manufacturers to delay the entrance of generic competition by drawing out negotiations over REMS patent licenses, forestalling the ability of generic manufacturers to apply for a waiver: a kind of filibustering, even. Ultimately, according to one source, less than 10% of FDA-approved REMS ended up having the shared system.

In December 2019, Congress passed the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples Act (CREATES) Act, which included provisions to address the inability for generic and brand manufacturers to agree on a shared system REMS.

Under the CREATES Act, a generic manufacturer is no longer required to use a SSS unless it receives an FDA waiver. Generic manufacturers instead may now choose from the outset to submit approval for a “separate REMS.” Notably however, the FDA may only “accommodate different, comparable aspects of the” ETASU between the generic manufacturer’s REMS and the brand manufacturer’s REMS. Although it addresses the problem of negotiating over REMS patents, the new law therefore still leaves unsolved the problem of potentially infringing those REMS patents.

REMS Example: Zyprexa for Schizophrenia

Zyprexa Relprevv, a brand name product that’s an extended release injectable suspension of olanzapine, is an antipsychotic that’s used to treat schizophrenia. However, the drug can cause serious adverse reactions where post-injection delirium sedation syndrome (PDSS) occurs. The risk of PDSS is less than 1% per injection, but the consequences can be severe.

As such, the FDA mandated the manufacturer of Zyprexa Relprevv to develop a REMS which stipulated that the drug must be administered in certified healthcare facilities, with patients receiving 3 hours of observation by a healthcare professional post-injection.

Psychedelics REMS?

It is likely that the FDA will require a REMS for psychedelic therapies, such as MAPS’ MDMA-assisted therapy. This could come in the form of therapist training and accreditation in-line with MAPS’ training manual, for example. Speaking to Fierce Biotech, MAPS PBC CEO Amy Emerson explained:

“The FDA was unsure what to do with the therapy part of it. Do they look at the therapy training program? What is the label going to say? How much do you put in the REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] and how much do you put in the label?”

REMS programs can also be generated for an entire class of drug, such as the Opioid Analgesic REMS which was approved in September 2018 and covers oxycodone, hydrocodone and morphine, among other drugs.

Might we see a similar pan-psychedelics REMS program in the future, at least for psychedelic-assisted therapies?

Perhaps. But, it’s likely that the FDA will evaluate psychedelic therapies on a case-by-case basis, at least to begin with. New Drug Applications for psychedelics are likely to be few and far between in the coming years, with only MAPS, COMPASS Pathways, and Usona Institute engaged in late-stage trials. It’s also worth highlighting that ‘psychedelics,’ especially as currently imagined, are not a homogenous class of drugs. MDMA, for example, is an empathogen. As such, it has different properties to classic psychedelics such as psilocybin and DMT.

Patenting REMS

Now, on to the collision between REMS programs and patents. Importantly, brand manufacturers can attempt to prevent generic competition by patenting the REMS programs themselves. Even where a generic manufacturer obtains a separate REMS allowing them to deviate from the brand manufacturer’s REMS program, the generic may still infringe the brand’s patented REMS program. The FDA, after all, does not make judgments on patent scope or infringement liability. Will “comparable” aspects of the ETASU still fall within the scope of the brand manufacturer’s REMS patent claims?

And to the extent other REMS aspects are still shared, the generic’s product label must include those aspects of the REMS program that also appear on the brand’s label. As such, if the brand has successfully patented its REMS program, the generic is put in a very difficult situation. The generic can either include the REMS program in its product packaging and be liable of inducing infringement of the patent, or omit the REMS program thus violating FDA packaging rules.

i.e., FDA regulations require generics to copy brand labels, and thus they may be copying a patented REMS program in doing so.

“As a result, generics seeking to introduce REMS programs are stuck between the rock of FDA regulations and hard place of patent law.”

Carrier and Sooy, 2017 (pp. 1680)

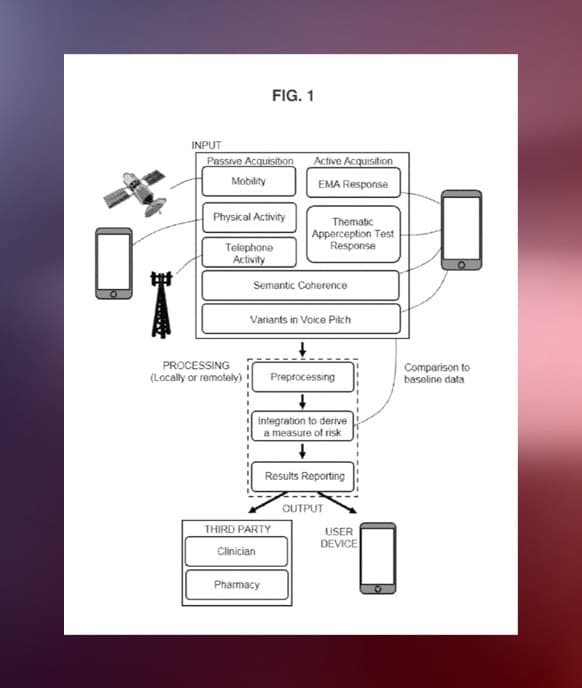

Beyond this explicit copying of labelling, a REMS patent could be more convoluted. It might, for example, cover an algorithm that uses patient data to calculate the risk of an adverse event. The data used to generate the algorithm may have been derived from clinical trials of the drug, adding another proprietary element.

So, could the patenting of REMS programs be the next frontier in the apparent psychedelics IP skirmish?

Eleusis, one of the earliest psychedelics R&D companies, has a number of published patent applications which seek to cover the screening and monitoring of those undergoing psychedelics therapies.

One such application covers a method of screening candidates for psychedelic therapy through analysis of a language sample. Claims 59 and 167 specifically mention a machine learning algorithm that may be employed to augment the analysis of such a sample.

A more recent patent application by Eleusis seeks to cover methods of monitoring a psychedelic therapy session, and specifically notes in the description that elements of the invention “may be based on a predetermined risk management plan (e.g., a European Medicines Agency (EMA) Risk Management Plan and/or an FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS))”.

***

As the psychedelic IP landscape continues to take shape, and the number of patent filings climbs, might we expect REMS-related patents to be of increasing interest to investors and entrepreneurs?

Other Headlines

- Bright Minds Biosciences provides scientific update;

- DemeRx (an atai company) doses first subject in Phase 1/2a study of ibogaine for opioid use disorder;

- Mindcure signs exclusive digital clinical data licensing agreement with ATMA Journey Centers;

- Mindset Pharma announces further preclinical results re: 5-MeO-DMT inspired drug candidate MSP-4018;

- Mycrodose Therapeutics completes oversubscribed private placement;

- Mydecine files MYCO-003 patent application, reports preclinical data;

- Small Pharma completes Phase I trial of DMT-assisted psychotherapy;

- Tryp Therapeutics submits IND application for Phase 2a clinical trial in eating disorders.

Read more on our News page.

Weekend Reading

Newsweek: Magic Mushrooms May Be the Biggest Advance in Treating Depression Since Prozac

Earlier this week, Newsweek unveiled the cover story for their October 1 issue which claims psilocybin “could be the biggest advance since prozac.”

Prominent Psychedelic Researcher Receives Grant From U.S. Government

Matthew W. Johnson announced, via Twitter, that he has received a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to study psilocybin for tobacco addiction.

It’s official. I just receive a U01 grant from NIDA to study #psilocybin for tobacco addiction. To my knowledge it's the 1st grant from the US government in over a half century to directly study therapeutics of a classic #psychedelic. New era in legitimacy of psychedelic science.

— Matthew W. Johnson (@Drug_Researcher) September 20, 2021

Other Headlines

- VICE: Psychedelics Are a Billion-Dollar Business, and No One Can Agree Who Should Control It

- Forbes: From Sugar To Psychedelics: The European Companies Testing Biosynthetic Psilocybin In Humans

- OZY: Mental Health, with a Side of Psychedelics?

Marijuana Moment: Italian Referendum to Decriminalize Psilocybin, Among Other Psychoactive Plants, Gets Half a Million Signatures

Weekly Bulletins

Join our newsletter to have our Weekly Bulletin delivered to your inbox every Friday evening. We summarise the week’s most important developments and share our Weekend Reading suggestions.

Live Updates

Join us on Twitter for the latest news and analysis.

Other Channels

You can also find us on LinkedIn, Instragram, and Facebook.