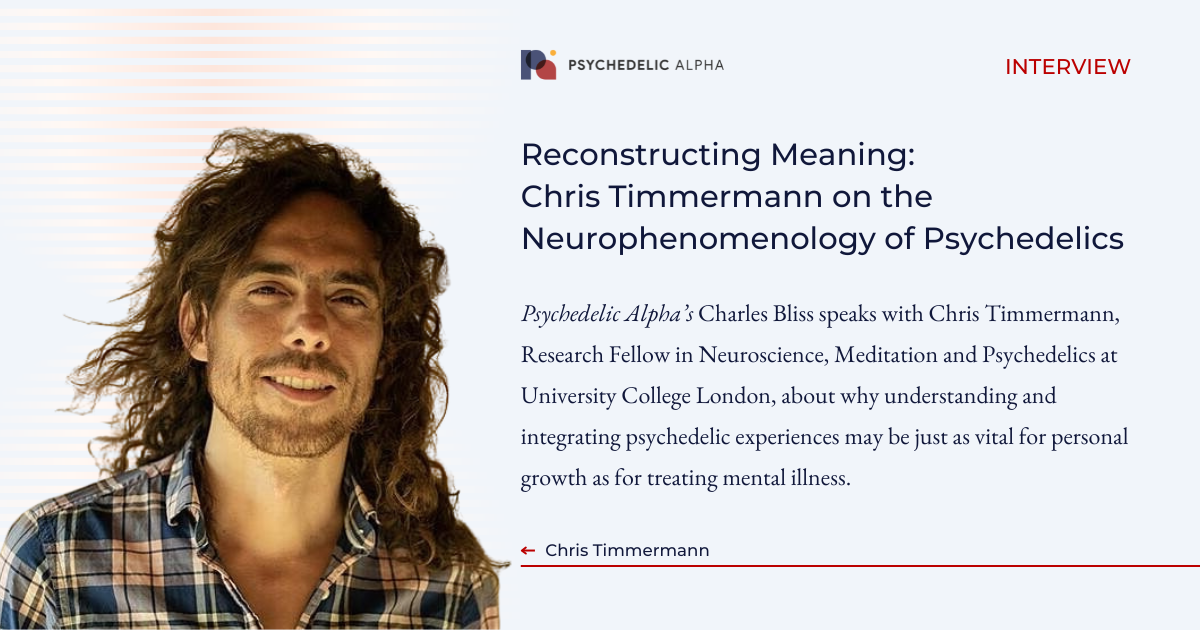

Chris Timmermann PhD is one of the UK’s leading researchers at the frontier of consciousness science. A Research Fellow in Neuroscience, Meditation and Psychedelics at University College London, and former Head of the DMT Research Group at Imperial College London’s Centre for Psychedelic Research, his work explores how psychoactive compounds like DMT and 5-Meo-DMT affect the human mind—and what they might reveal about the nature of consciousness.

Timmermann uses a neurophenomenological approach in his research, which seeks to integrate the first-person subjective experience of psychedelics (i.e., how we feel, perceive and make meaning) and third-person, objective neuroscience data (e.g., brain imaging or electroencephalogram tests). Rather than attempting to reduce psychedelic effects to brain chemistry alone, neurophenomenology investigates how first-person accounts of altered states can be correlated with measurable changes in neural activity.

In conversation with Psychedelic Alpha, Timmermann talks about the neuroscience of meaning-making, why subjective experience matters, and how altered states can help us cultivate new ways of engaging with our lives.

Charles Bliss, Psychedelic Alpha: What drew you to the field of neurophenomenology, and why do you think it’s important in the context of psychedelic research?

Chris Timmermann: The main motivation is to introduce the richness of lived experience into the way that we do science—concerning consciousness more broadly, but especially around psychedelics.

And why is that? Because all the evidence points towards experience as being a primary driver in terms of the mental health benefits of psychedelics, as well as the contributions of psychedelics towards a larger understanding of the mind.

That’s what drives this idea of neurophenomenology as a discipline—the way in which we introduce that lived experience in the way that we do science about psychedelics.

Take the idea of the sense of self. You have the acute ego dissolution experience, but in the longer term, that offers a new way in which the sense of self can re-emerge. There are all these opportunities of how we structure ourselves and our lives that are meaningful.

Bliss: At a time when non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens are being engineered to eliminate the trip, why is it important to understand more about the neuroscience behind the subjective experience of drugs like DMT or psilocybin?

Timmermann: There’s such a big black box around those qualities of subjective experience that, in the psychedelic space, are wrapped around narratives of transcendental stuff or new age stuff or mystical stuff that we are not really addressing in a way that feels sustainable to me.

By trying to employ a rigorous phenomenological approach to understanding these experiences, we can learn more about them: the risks, the potential ethical issues that arise around false memories in psychedelic therapy, for example.

Bliss: At Breaking Convention 2025, you said that researchers are interested in psychedelics because they modulate fundamental structures of experience, while offering novel opportunities for meaning-making. This reminds me of the ‘shaking the snow globe’ analogy—a perturbation or disturbance to the system which could help us understand the brain.

Timmermann: That subserves why I think psychedelics are interesting for us researchers trying to understand consciousness, but in terms of the mental health applications it’s more than the ‘snow globe’ approach.

I converge with this idea that psychedelics offer opportunities to act on broader mechanisms that underline many mental health conditions, and that can also support existential development in a broader sense. So, not just mental health conditions, but also the betterment of people without underlying, overt clinical psychopathologies as well.

It [the psychedelic experience] restructures the ways that we engage with the world—and by doing so, that restructuring itself brings forth opportunities to develop meaning again.

When an individual is faced with this deconstruction of these fundamental aspects of the human mind and brain, in that reconstruction they can develop novel ways of engaging with life.

Take the idea of the sense of self. You have the acute ego dissolution experience, but in the longer term, that offers a new way in which the sense of self can re-emerge. There are all these opportunities of how we structure ourselves and our lives that are meaningful.

Why is it so important? Because meaning is so essential for our wellbeing, and so essential for the ways that we engage with life more broadly. It really is the primary motivator in many ways.

Bliss: What is it about psychedelics that makes them such compelling instruments for exploring the relationship between first person, subjective experiences and third person, objective science?

Timmermann: This first person versus third person approach really speaks about a primordial position that we have as human beings.

We have access to our own minds—and that is subjectively true and intimate and very valuable to us. Think about mental health. Mental health is about our own subjective states of mind.

On the other hand, you have this external world that we’re always facing and that we try to make sense of with the enterprise of science. We validate things by having two people pointing at the same things out there and saying this is what we’re learning about the external world. That’s science in a nutshell—and the idea of neuroscience in many ways.

A big part of our existential conundrum as human beings is that we have a gap. We have that separation between the intimate, subjective, lived experience and the things out there that we can verify in the world.

The fascinating thing about psychedelic drugs is that they appear to build this bridge between the first person and the third person worlds. They’re hardcore molecules that you find in the world out there that induce these very intimate, significant, subjective, private experiences.

I think this is what brings about all the mystique and fascination around psychedelics. It seems that something is being revealed about the nature of things.

The whole idea of neurophenomenology is that you’re never going to solve this—but you can navigate it. How you navigate it is not by reducing experience to brain activity only, not by just caring about subjective experience and saying the brain or the material stuff is secondary, but having them engage in this dance.

Bliss: Is that why you’re not just focusing on psychedelics? Your research programme is also investigating other non-ordinary states of consciousness such as meditation and flow states.

Timmermann: It’s because they speak about a cultivation of how to navigate these things.

Meditation is not just about achieving an altered state of consciousness. Instead of the person who trips for the first time, finds God and then goes back to their everyday life, meditation is about cultivating traits that will allow you to navigate that space.

But it’s also about developing a form of meaning that emerges that is long lasting—where these practices are integrated and those insights can be sustained and bridged into their everyday life. Flow states are another way in which you cultivate some form of practice within the psychedelic state that could be beneficial.

The great benefit of trying to incorporate some contemplative practice or meditation in that way is to not exceptionalise that psychedelic state as this, ‘I went into the realms of the hyperspace or the unknown and I’m saved’.

But rather, how is it related to this everyday world that I’m in? How is this related to the way that I take care of my family? How is this related to the way that I engage with other people? How is this related to the ways that I cultivate traits of compassion?

That’s the same as what happens in a psychedelic session where you’re confronted with this ocean of information—all these insights. How do you figure out the things that are useful? How do you navigate them with your phenomenology?

You’re trying to understand that this is an inquiry into my mind—and whatever is shown is a process of open-ended learning, rather than the final attainment of reaching the top of the pyramid and being enlightened.

This interview has been edited for length, structure and clarity.

You might also like…

Q4’25 Psychedelic Lobbying Update

Taking the Helm at Helus: A Brief Q&A With New CEO Michael Cola

The Psychedelic Practitioner Issue 3: Dosing