From 17–19 April, the UK’s seventh biennial psychedelic conference tackled some of the field’s most urgent questions.

In this second instalment, we explore:

- the ethical dilemmas of giving psychedelics to young people,

- the critical role of therapist selection,

- how female biology affects drug interactions,

- the pros and cons of non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens, and

- what it really means to integrate psychedelic insights.

***

Words by Charles Bliss for Psychedelic Alpha.

Every year on 19 April, psychonauts and scientists alike mark Bicycle Day—the anniversary of the world’s first intentional acid trip. In 1943, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann swallowed 250 micrograms of LSD-25 and set off on a bike ride that would change the course of psychedelic history.

More than 80 years later, 1,400 delegates gathered at the University of Exeter for Breaking Convention—one of the world’s leading psychedelic science conferences—to explore where that journey has led us.

This report takes you inside the final day of talks, debates and discoveries at Breaking Convention 2025. In case you missed it, read a recap of the rest of the weekend in part one here.

The Ethics of Psychedelic Pediatrics

Adolescence is hard… The process of going from being a child to being an adult is difficult. The intrapsychic, interpersonal tasks that you have to fulfill to get to being an adult—like developing agency, developing your social identity, individuating from your parents, becoming your own person—those are complicated and distressing.

Eddie Jacobs

On Saturday afternoon, Eddie Jacobs from the University of Oxford’s Department of Psychiatry offered a cautionary perspective on the ethical implications of administering psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) to adolescents.

The effects of psychedelics have barely been studied in children or teenagers, as most research so far has focused on adults. In the U.S., the Pediatric Research Equity Act allows the FDA to require that drug companies also study how a treatment affects younger age groups. These studies must be tailored to different stages of childhood and adolescence, using age-appropriate doses and formats. If a drug is being developed for adults, it generally also needs to be tested for safety and effectiveness in children—unless it is “waived, deferred or inapplicable” by the FDA. The aim is to gather enough data to officially approve the drug for use in young people. As an added incentive, drug companies that carry out paediatric studies can be rewarded by regulators with additional exclusivity periods before generic versions of their products are allowed on the market.

While a number of trials involving MDMA and other investigational drugs for adolescents are in the planning phase—particularly in the US and UK—Jacobs emphasised the need for a robust ethical framework before these studies progress, especially given the developmental differences between adults and teenagers. Rather than debating whether these trials should happen, he focused instead on how to optimise their safety and effectiveness as they inevitably arise—especially by considering the adolescent’s environment.

He invoked psychologist and early LSD researcher Betty Eisner’s concept of the “matrix”, originally proposed in the 1960s, which refers to the broader sociocultural and emotional context that patients come from and return to after psychedelic treatment. Jacobs described how most of a patient’s life happens outside the clinic—their familial relationships, social support, home life—which significantly influences therapeutic outcomes.

Jacobs pointed out that young people are especially vulnerable because they have less “agency” to change their environments compared to adults. School and family dominate their lives, and they often have little control over sources of stress or dysfunction at home. This means that adolescents are more dependent on and less able to modify or escape the environment in which their mental distress emerges, he said.

“Adolescence is hard,” Jacobs said. “The process of going from being a child to being an adult is difficult. The intrapsychic, interpersonal tasks that you have to fulfill to get to being an adult—like developing agency, developing your social identity, individuating from your parents, becoming your own person—those are complicated and distressing.”

He highlighted that one effect of the increased neuroplasticity following PAT is that patients have heightened environmental sensitivity, which can either support healing or reinforce distress. Jacobs suggested this necessitates a framework that considers the family system and broader social matrix as determinants of therapeutic outcomes.

Jacobs predicted that the best case scenario, if the matrix does not change or improve, is that the patient could experience some symptom relief from PAT, but these benefits may fade. The worst case scenario could be that psychedelics make the adolescent more sensitive to the same harmful environment, deepening the problem.

To illustrate this point, Jacobs proposed a hypothetical case study called Johnny, a fictional 17-year-old who did not respond to multiple treatments. His depression may not stem from internal pathology, but from family dynamics and developmental conflict (e.g., pushing for independence but facing resistance). Psychedelics could help, Jacobs said, but without changes in his family environment, the benefit may not last—or could even be deleterious.

Jacobs also used the example of a mouse given an SSRI: while it struggles harder to escape a trap, if the environment is unchangeable, the effort doesn’t help. “One reason that we were originally confident that SSRIs have antidepressant action is because if you give [these] animals SSRIs and then hang it by its tail on a peg, it will struggle and wriggle for longer trying to get off the peg,” he said.

This is a test of “active and passive responses to a stressful situation”. The SSRI was seen to be working because the mouse was more motivated to exert effort to improve its situation.

“When you’re depressed, ultimately, whatever treatments you’re getting, there’s a large part of the immune response that comes from you and your engagement with the environment,” Jacobs said. But even the mouse benefiting from SSRI treatment has no agency to change its situation, despite its effort.

“That mouse could struggle and struggle and struggle and it won’t get off that peg because it’s in a situation that it can’t escape from—and that’s no shame on the mouse,” Jacobs said. “It’s just in an environment that is not within its power to change.” Similarly, psychedelics could heighten a teenager’s sensitivity without giving them tools or power to change or escape damaging environments, he suggested.

In an interview with Psychedelic Alpa, Jacobs noted that despite improvements in the field’s tone compared to five years ago, when there was an “irrational exuberance and enthusiasm” surrounding PAT, he still has ethical concerns about the right approach. And the stakes are even higher when it comes to adolescents. “I’ve just got this residual concern that there might still be an element of haste to it that isn’t necessarily appropriate,” he said.

He pointed to a broader trend in psychiatry where medications are frequently prescribed off-label to under-18s without sufficient pediatric trials. Psychedelic research risks replicating this pattern, particularly if adult models of treatment are directly applied to adolescents without rethinking developmental, metabolic and psychosocial differences, he told us.

Rather than focusing solely on pharmacology, Jacobs urged researchers to consider how factors like family systems, discrimination and cultural setting shape outcomes. For adolescents, this means embedding trials within a more holistic support network. Drawing inspiration from family and systemic therapies, he proposed trial models where integration work involves the adolescent’s wider support system—parents, caregivers or family members.

“It’s not about finding who’s to blame or what have you, but just thinking about what things can change within the system to the benefit of the teenager,” he told Psychedelic Alpha.

In his talk, Jacobs suggested one solution could be psychedelic-assisted family therapy. Although not every family member would necessarily take psychedelics, the goal would be to understand and address dysfunctional family patterns that contribute to a young person’s depression. Sometimes, it might even be more helpful for a parent, not the adolescent, to receive PAT. It would be essential to ensure comprehensive screening, family involvement and enhanced integration support to ensure safe, effective and ethically sound interventions for vulnerable adolescent populations, he said.

Jacobs also discussed the utility of Phase 4 (post-marketing) trials as a better fit for these more flexible, family-inclusive models. Unlike the tightly controlled environments of Phase 2 and 3 studies, Phase 4 trials allow real-world variables to play out, providing a more accurate picture of how treatments work in practice. This is especially important, he argued, for adolescent populations where rigid standardisation may obscure important contextual factors.

Jacobs closed by pointing out that MAPS has already used MDMA-assisted therapy with couples where only one partner had PTSD. He said this demonstrates that changing a broader system, not just the “identified patient”, can drive healing.

Protocols for Mitigating Risk

The biggest thing we can do for mental health treatment, generally, is to very, very, very carefully select the people who treat mental health problems.

Ian Jordan

Clerkenwell Health’s Clinical Director Iain Jordan outlined the often-underdiscussed risks of psychedelic-assisted therapy—and how his contract research organisation (CRO) is working to manage these factors through specialised protocols, recruitment and training to prioritise both patient and therapist safety.

Jordan began by stressing the need for establishing rigorous safeguards in clinical trials and creating supportive therapeutic settings to help minimise adverse reactions. He noted that psychedelics are given to people in fragile psychological states which, combined with the unpredictable nature of psychedelic drug interactions, makes the risk profile of this model of therapy distinct.

Physical risks such as elevated heart rate and blood pressure are manageable, Jordan said, but psychological risks are amplified. These include phenomena that are “quite specific to psychedelic research” such as metaphysical or ontological shifts, psychosis, PTSD, reactivations and hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD).

Jordan also highlighted the often overlooked potential for harm posed by placebos in clinical trials. For those with treatment-resistant conditions, PAT can offer the promise of an effective intervention for debilitating disorders such as depression. But if these patients are primed for the psychedelic experience and ultimately receive a placebo, this can not only disappoint but cause distress to participants.

“No matter how much we prepare people and talk to them about it beforehand, it can be devastating to go into the room after two months of preparation and to take the medication and [for] nothing to happen,” Jordan said.

Others face what Jordan called “context mismatch”—whereby a patient who undergoes a positive therapeutic intervention returns to an unsupportive environment after the trial. He cited the case of a PTSD patient who had an “absolutely extraordinary improvement” after one treatment with methylone. But at home, her partner found it “impossible to deal with the fact that she was no longer this fragile person” and violently assaulted her. Therefore, the entire set, setting and social matrix, as Eddie Jacobs discussed earlier in the day, must be accounted for by therapists. (Two years later, the patient has left the relationship and is doing well.)

Jordan added that it is “really important to balance risks and harms and also to not be afraid of risk”. In the context of PAT, he compared this process to surgery, which presents both benefits and potential dangers. This is ethically acceptable as long as “people are adequately consented and informed and cared for”, he said.

Jordan emphasised that the most important factor for improving psychedelic health care is selecting the right therapists—not just those with credentials, but those with innate interpersonal skills. He explained that Clerkenwell Health’s recent hiring process saw 2,200 applicants for two vacancies. But the company’s rigorous recruitment criteria, assessing empathy, adaptability and self-awareness, saw only one candidate suitable for the role.

“The biggest thing we can do for mental health treatment, generally, is to very, very, very carefully select the people who treat mental health problems,” Jordan said. “There’s a small group of people with a certain set of characteristics who are really, really, really effective practitioners. I think what we should do is find those people.”

He dismissed the idea that therapists need personal psychedelic experience. Instead, he stressed transferable skills: sitting with distress, reframing traumatic experiences and avoiding ideological imposition. One patient who initially felt like a “failure” during a session later reinterpreted it as a breakthrough in trust thanks to guidance from therapists, he said.

Jordan closed by underscoring the need for humility. “It’s not rocket science,” he said, but it demands meticulous care—from therapist selection to post-trial support—to manage the transformative, yet destabilising, potential of PAT.

Designing Research With Women in Mind

We do need to understand sex as a biological variable in the context of psychedelic use—not only so that we can ensure that all women who are going to go and have these treatments in the future are definitely safe enough to do it, but also because I think there is an incredible amount of opportunity for women to really find medicines that are going to be incredibly healing and helpful for us.

Grace Blest-Hopley

Neuroscientist and Founder of Hystelica Grace Blest-Hopley delivered a powerful talk highlighting the underrepresentation of women in psychedelic research, the knowledge gaps in the intersection between female biology and psychedelics, and the significant consequences this has for mental health treatment and clinical outcomes.

Blest-Hopley exposed how women are frequently treated as outliers in psychedelic science, despite being disproportionately affected by many of the conditions that psychedelics are being developed to treat.

“Women are not seen as usual,” she began. “We’re not seen as the norm within the psychedelic space, and we’re not researched as such. And for me, I think that is a huge problem.”

She pointed out that women are more likely than men to experience depression, anxiety and autoimmune diseases, as well as postpartum trauma and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). These conditions are often influenced by hormonal changes throughout the menstrual cycle and across the lifespan—factors that are rarely accounted for in clinical research. One particularly stark example she cited was the 27% increase in female suicidality during the late menstrual phase, compared to a 19% rise in suicide attempts, suggesting not only an increase in risk but also in lethality.

“Women are not little men,” she said. “We have a whole set of biology, which is our hormonal fluctuations that take place throughout our menstrual cycle and then as we transition into later life and menopause… They also have a huge impact on our brain and on our neuropsychopharmacology. And not only do they have that impact, but they also do so via mechanisms that are remarkably similar to that of a number of psychedelics.”

Blest-Hopley gave an overview of the menstrual cycle, explaining how fluctuations in oestrogen and progesterone—both powerful neurosteroids—affect brain function. High oestrogen levels, for example, are linked to increased neuroplasticity, memory formation, dopamine sensitivity and serotonin activity. In contrast, the drop in hormones during the late luteal phase and after menopause can result in heightened vulnerability to anxiety, depression, cognitive decline and even psychosis, she said.

She argued that these hormonal dynamics are not just background noise but are deeply relevant to how psychedelics work. Psychedelics and oestrogen both modulate the serotonergic system, enhance neuroplasticity and influence stress responses, she said.

“We do need to understand sex as a biological variable in the context of psychedelic use, not only so that we can ensure that all women who are going to go and have these treatments in the future are definitely safe enough to do it, but also because I think there is an incredible amount of opportunity for women to really find medicines that are going to be incredibly healing and helpful for us.”

Yet most trials still fail to account for where a woman is in her cycle, resulting in inconsistent data and potentially substandard or even unsafe outcomes. “It starts [with] actually asking the f***ing question: where are you in your menstrual cycle?” Blest-Hopley said.

She raised concerns about safety, especially when women undergo psychedelic experiences during their menstrual cycle. She questioned the appropriateness of certain settings, such as long ceremonies, for women experiencing physical discomfort or heightened emotional sensitivity.

“If you’re somebody who really, really struggles at the latter part of your menstrual cycle,” she said, “do you really want to be lying on the floor of a maloca for the next eight hours? Do you really want to change your tampon in the middle of an acid trip? Probably not. So we need to definitely think about where women are in their menstrual cycles so that we are making sure they’re having the most optimal experience.”

She emphasised the need for observational studies that capture real-world psychedelic use among women, and for building from Indigenous science and knowledge systems that have long recognised the importance of menstrual and hormonal states in ceremonial contexts. “We know that there are certain traditions who will not let women go into ayahuasca ceremonies when they are on their period,” she said. “And there’s probably a reason for that, right?”

Blest-Hopley also discussed the psychosocial dimensions of women’s mental health—such as trauma, violence and microaggressions—which intersect with biological vulnerabilities.

In closing, she called for a shift in how psychedelics are studied and applied. Without data on how psychedelics interact with female biology, particularly during pregnancy or breastfeeding, practitioners cannot offer informed advice. “Right now, we do not understand what optimal, safe psychedelic use looks like in women’s bodies, because nobody has been measuring it,” she said.

However, she was positive about the future: by prioritising research into female-majority conditions such as eating disorders, PMDD and menopause-related symptoms, the psychedelic field could not only become more inclusive but also more effective. She urged the audience to demand better science and to push for a psychedelic field that not only accounts for sex-based differences but sees them as essential to improving mental health outcomes for half the population.

Eliminate the Trip?

It may well be that the experiential fireworks of psychedelics are just an epiphenomenon of something that's occurring on a deeper neurological level, and that by stimulating the neurological plasticity and the growth that occurs in the brain after an ingestion of a psychedelic, we can elicit the same kind of therapeutic benefits.

Ido Hartogsohn

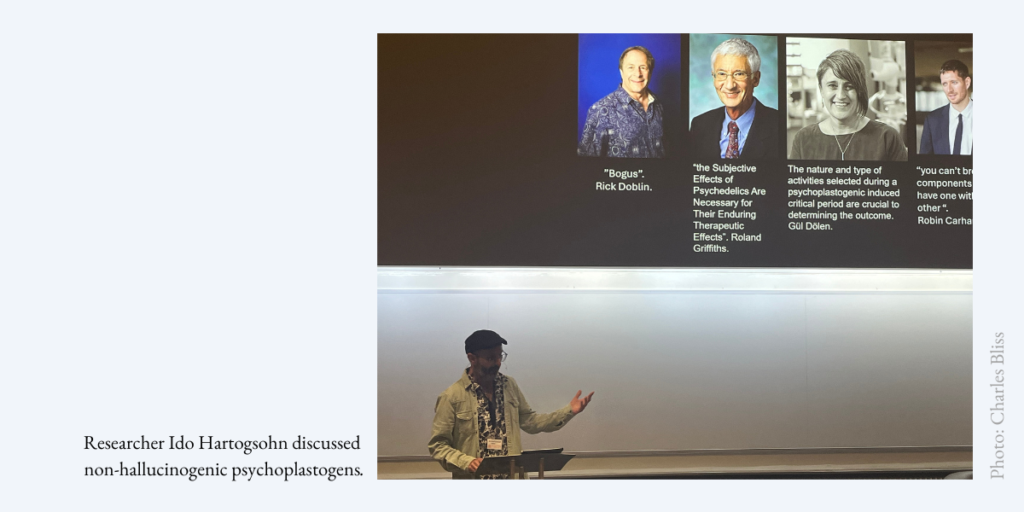

Researcher Ido Hartogsohn presented a provocative argument about the push to develop non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens—molecules that mimic the therapeutic effects of psychedelics without the “trip”. His talk examined the scientific, cultural and ethical tensions surrounding these novel compounds.

“Why would anybody want to eliminate the trip? Why would you want to obliterate the psychedelic experience with all its beauty and lessons?” he said. “But it turns out there are some valid reasons for attempting to create such non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens.”

Hartogsohn started off by acknowledging the backlash from psychedelic communities, where the subjective experience is often seen as central to healing. Yet he outlined practical reasons for pursuing non-hallucinogenic alternatives.

First, accessibility could be improved as patients with mental health risks or fears of traumatic trips could still benefit. Second, the drugs might bypass the need for costly psychotherapy, boosting scalability by making treatment cheaper and more FDA-friendly. Third, removing the trip element neutralises the risk of ‘bad trips” and negative psychological fallout or retraumatisation, Hartogsohn said.

He cited a study in which ketamine was administered during sleep that suggested therapeutic effects may occur independently of conscious experience. Though psychedelics are “first-generation” psychoplastogens, newer, non-hallucinogenic versions such as Delix Therapeutics’ AAZ-154 could be safer and more precise, he said.

Hartogsohn referenced critics of this approach including Rick Doblin and Robin Carhart-Harris, who have argued that the experience is irreplaceable and have compared non-hallucinogenic chemicals to “psychedelic tofu”. Hartogsohn noted the culture’s emphasis on challenging trips as catalysts for growth, citing ayahuasca’s purging rituals.

“When we take this romantic component into account, psychedelic voyages emerge as personal trials that demand courage and resilience and strength,” he said. “So following Nietzsche’s dictum that ‘whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’, we can think about psychedelics as Nietzschean molecules—and [this] also follows the idea that the capacity for pleasure stands in direct proportion [to] our capacity for suffering.”

Hartogsohn questioned whether stripping psychedelics of their experiential dimension reflects a Western urge to sterilise discomfort. He linked it to trends like decaf coffee, non-alcoholic beer and virtual sex—and warned that this “extractive colonialist logic” could reduce psychedelics to mere neurochemical tweaks, divorcing them from their radical, “liberatory potential”.

He added that, on the face of it, these compounds look like an attempt to purge psychedelic medicine of its transformative experiential power and turn it into a “zombie-like process of neurochemical manipulation”. But he said this “false binary” runs the risk of ignoring legitimate reasons for developing such tools.

Hartogsohn remained agnostic about their future. They might fail, dominate psychiatry or even fulfil Aldous Huxley’s dream of an “ideal drug” without adverse side effects. Either way, he argued, the debate forces us to ask: What do we value about psychedelics?

Psychedelic Insight in Uncertain Times

When strategy stops working, you need to get weird. You need to get used to travelling in liminal spaces.

Alexander Beiner

On Saturday evening, Breaking Convention Executive Director Alexander Beiner argued that the felt, emotional and perceptual effects of psychedelics are central to their value, as he re-evaluated Alan Watts’ famous slogan: “Once you get the message, hang up the phone.”

He criticised the quotation for being incomplete, as it suggests that psychedelics are merely tools to deliver insight, after which one should internalise this and should move on. But the subjective experience does not deliver neat messages, Beiner argued, and psychedelic wisdom cannot be distilled down to receiving one-off insights.

Beiner questioned whether this metaphor still holds true in a world undergoing profound disruption—the end of the liberal world order, the collapse of old ideologies, and the emergence of a post-strategy, post-certainty era. Instead, he claimed, we must reconceptualise the psychedelic experience as a method to develop durable psychological and social competencies to navigate the “metacrisis”—a cluster of existential risks we face as a species, including mental health, geopolitical instability, economic inequality, artificial intelligence and climate emergency.

“How can psychedelic experiences help us navigate the mad times that we live in, hopefully towards a more generative pro-social future?” he said. “When strategy stops working, you need to get weird. You need to get used to travelling in liminal spaces.”

Beiner, the author of The Bigger Picture: How Psychedelics Can Help Us Make Sense of the World, proposed that traditional leadership models are failing and argued that what is needed in moments of profound uncertainty is a “shamanic” mode of navigating reality. He claimed that psychedelics, understood through the lens of cognitive science, can train us to navigate complex environments by developing embodied intelligence, flexibility, discernment and the ability to thrive in chaos.

This also includes learning to embrace discomfort, distinguish truth from illusion and relate more skillfully to others, he argued. Just as walking on hot coals develops transferable courage and focus, Beiner said, so psychedelic experiences can shape competencies applicable in daily life.

“What’s happening when you walk across [hot coals] is that you’re developing skills that you can then apply to other domains in your life,” he said. “You have to walk not too fast and not too slow…You have to be committed. Keep your eye on the prize. Be brave, be courageous, and then do it right.”

In Beiner’s view, contemporary society is saturated with information but starved of wisdom—the capacity to act meaningfully and ethically in complexity. Psychedelics, he argued, offer access to wisdom by helping individuals discern what matters, not just intellectually but emotionally, spiritually and relationally.

But Beiner cautioned against overvaluing insights gained during psychedelic experiences without proper frameworks for interpretation because they can generate powerful yet misleading convictions. He noted that Indigenous cultures often possess rich cosmologies that guide psychedelic use responsibly, while modern Western societies are only beginning to develop such systems.

He also discussed the renewed interest in alternative applications of psychedelics beyond mental health, such as conflict resolution, leadership and creative innovation. He remained curious about different practices that could be combined with a psychedelic state to elicit new ways of seeing and hopefully new ways of solving massive global problems.

In closing, Beiner suggested that “hanging up the phone” does not mean leaving psychedelic wisdom behind but embodying it fully. Rather than viewing psychedelics as instruments that deliver messages, Beiner argued, they cultivate “meta-competencies”.

“It’s about receiving meta-competencies and skills that change who we are, how we see the world,” he said. “Then it’s about applying those psychedelic skills and perspectives to transform our institutions, change cultural norms, change technology, and deepen our authentic relationship between ourselves, one another and the cosmos.” ∎

In case you missed it, you can read Part 1 of this Dispatch here.

You might also like…

Taking the Helm at Helus: A Brief Q&A With New CEO Michael Cola

The Psychedelic Practitioner Issue 3: Dosing