Below, we explore a number of research themes that proved salient in 2022. It’s quite a long webpage, so you might prefer to use the contents table below (and the ‘scroll to top button’ in the bottom right-hand-side of your screen) to dip in-and-out of different topics.

Contents

Meta: Psychedelic Research Trends

Three charts that demonstrate how psychedelic research and clinical trials continued to ramp up in 2022:

Evaluating the Role of the Therapeutic Alliance

The partnership between a patient and their therapist has long been thought to be an influential and consequential aspect of traditional psychotherapies. This patient-provider relationship, known as the ‘Therapeutic Alliance’, is often recognised for its complex, dynamic, and intersubjective nature. In spite of these theoretical intricacies, a number of specific features and constructs have been identified as playing a crucial role in mediating the quality of the therapeutic alliance: aspects such as levels of trust between a therapist and patient, a collaborative relationship, and a mutual agreement on the objectives of therapy.

Given the essential role that therapists play in many psychedelic-assisted therapy protocols, many would assume that the quality of therapeutic alliance will be an important factor in determining the success of PATs. Despite this, little formal research has evaluated the precise role that the therapeutic alliance might play in eliciting the apparent benefits of PATs. However, over the course of 2022 a number of studies and publications began to add to what is now a prominent, and somewhat contentious, topic.

In March, researchers at Imperial College London published results of a study that sought to shed more light on this emerging area of research. In this study by Murphy et al. (2022), researchers performed a re-analysis of Imperial’s previous Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression1 (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021) in an attempt to better understand, “the relationships between the therapeutic alliance and rapport, the quality of the acute psychedelic experience and treatment outcome” (Murphy et al., 2022).

The researchers found evidence to support the conventional belief that the quality of a therapeutic alliance is associated with better therapeutic outcomes for participants who had undergone psilocybin-assisted therapy. Specifically, the strength of the therapeutic alliance and rapport between the therapist and patient was found to predict experiences of emotional breakthrough and mystical type experiences, both of which are frequently regarded as integral to positive treatment outcomes.

Researchers also described how a strong therapeutic alliance and rapport (measured between the first and second dosing sessions) led to increased emotional breakthrough and greater patient depression outcomes, respectively (Murphy et al., 2022).

The results of this study seem to align well with prevailing views of psychedelic-assisted therapy and reflect findings in earlier reviews of the importance of the therapeutic alliance in therapy2.

Although the Imperial study was the first to formally investigate the effect of the therapeutic alliance in a clinical trial of psychedelics, as aforementioned, the importance of the alliance has been implicitly or explicitly recognized in many other psychedelic studies and publications. In fact, in an April 2022 publication, Peter Oehen and Peter Gasser reflect on how MDMA-assisted therapy has been used in preparation for LSD-assisted therapy, in an attempt to enhance the therapeutic alliance in a patient population suffering complex PTSD3.

The importance of a strong therapeutic alliance for psychedelic-assisted therapy was also noted in an August 2022 paper by researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. In this publication Ortiz et al. (2022) discussed a number of “special considerations” that should be taken into account when establishing a therapeutic alliance with individuals from ‘vulnerable populations’, or those who have traditionally been left out of psychedelic research.

The authors explained that the lived experiences of these underrepresented and vulnerable groups may introduce new dynamics into the process of developing a therapeutic relationship that demand more reflexive, empathetic, transparent, and culturally competent care:

“Insofar that hardship, adversity, and maltreatment are daily realities for vulnerable populations in general – and especially in healthcare settings (e.g., Sorkin et al., 2010) – establishing therapeutic alliance may require dedicated time and specialised skills.”

Given this received wisdom regarding the importance of therapeutic alliance in PATs, many were surprised to learn that a post hoc analysis of COMPASS Pathways’ Phase 2b trial4 found that therapeutic alliance did not predict improvement in depressive symptom severity.

As in the Imperial study (Murphy et al., 2022), COMPASS’ post hoc analysis found that emotional breakthrough (as measured by the EBI) predicted therapeutic outcomes5. However, unlike the findings of the Imperial study, the latter found that, “[t]he direct effect of [therapeutic alliance] on depression outcomes was not significant for any path”.

COMPASS was keen to point out that its study represents a “larger, more robust TRD sample” than the Imperial group’s, with the poster’s authors also noting that, “effects in smaller trials are often not confirmed in larger samples.”

The authors speculate that the therapy model used in COMPASS’ trials (which, as we have mentioned elsewhere, is referred to as ‘psychological support’) may have less variance from therapist to therapist, and as such may have “less potential to differentiate outcomes”.

COMPASS appears to be pitching this lack of relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcomes as a benefit, given that less emphasis on the therapy element (which is even described as “a safety measure”, in the poster6) allows them to make the case that the drug is driving efficacy.

Contrast this pursuit of standardised, low-variance psychological support with the types of therapy seen in MAPS’ trials of MDMA-AT for PTSD, which provides a great deal of latitude7. Beyond differing philosophies among trial sponsors, might it be the case that aspects like the quality of therapeutic alliance and the flexibility with which a therapist can operate are more important for certain drug-assisted therapies than others? Given the effects of an entactogen like MDMA, it may not be surprising if patients undergoing MDMA-assisted therapy might benefit from a more ‘involved’ facilitator or therapist; versus, say, a patient undergoing psilocybin therapy, which might be more introspective and as such the therapist could adopt a less involved approach. It’s also possible that the importance of therapeutic alliance might differ between conditions, as alluded to above.

While 2022 was a productive year for this research topic, there’s still a dearth of data. Given that we only have two post hoc analyses of controlled studies, which produced conflicting results, the causal effect of therapeutic alliance on patient outcomes–if any–remains unclear. Nevertheless, ongoing research and discussions, such as those highlighted above, will undoubtedly shed more light on this topic.

A Closer Look at Drug Interactions

Drug-drug interaction (DDI) studies provide important information on how psychedelics might interact with other commonly prescribed medications, which can impact their safety and/or efficacy. Regulators may require (modern) DDI studies for labelling any approved psychedelics.

Over the course of 2022, a number of studies looked at interactions between psychedelics and commonly prescribed antidepressants.

One systematic review conducted by researchers at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) reviewed the existing body of evidence8 on interactions between various psychiatric medications and MDMA or psilocybin (Sarparast et al., 2022). Most of the studies identified (24) looked at the interaction between MDMA and psychiatric drugs like antipsychotics, anxiolytics, mood stabilisers, NMDA antagonists, and various antidepressant drug classes.

The review identified that the co-administration of MDMA with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can lead to dangerous adverse effects, and has “contributed to the majority of deaths cited in published case studies.” Beyond safety concerns, the authors also discuss how common antidepressants like SSRIs and SNRIs can dampen the subjective effects of MDMA. In fact, the authors found that citalopram, paroxetine, or fluoxetine “attenuated the subjective effects of MDMA by ~30 – ~80%, while physiological effects were attenuated by ~6 – ~14%”9.

A limited number of studies on the interactions between SSRIs and serotonergic psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin have arrived at mixed findings10. In order to explore these interaction effects, Natalie Gukasyan and colleagues at Johns Hopkins conducted an online survey of 595 individuals to explore “the extent to which serotonergic antidepressants may diminish psilocybin’s effects both concurrently and after discontinuation” (Gukasyan et al., 2022).

The Johns Hopkins study looked at the interaction between psilocybin and common antidepressants. It found that psilocybin’s effects may be diminished by serotonergic antidepressants acutely and even after a medication washout period. In roughly half of survey participants, the dampening effect persisted for as long as three months after discontinuing SSRIs11.

While not a drug interaction, a post-hoc analysis conducted using data from Imperial College London’s Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021) looked at the impact of recent antidepressant exposure on the effects of psilocybin. The results were presented by David Erritzoe at the Interdisciplinary Conference on Psychedelic Research (ICPR) in September 2022.

Kelan Thomas, PharmD shared with Psychedelic Alpha that:

“The Erritzoe ICPR post-hoc analysis figure very clearly illustrated that participants who had recently discontinued their current antidepressant medication for enrollment in their trial had a less robust psilocybin antidepressant effect, which was equivalent to escitalopram’s antidepressant response.”

Thomas also noted that moving forward, he hopes to see trials investigate whether increasing the dose of psilocybin administered to patients might help overcome the attenuating effects of recent antidepressant exposure seen in these studies.

However, these results stand in stark contrast to some released by COMPASS this year. In the Supplementary Appendix of their Phase 2b publication (Goodwin et al, 2022), a post-hoc subgroup analysis12 noted “no apparent difference in the efficacy response of participants withdrawn from antidepressant medication prior to baseline [n=53] compared with those who entered the trial drug-free [n=26].”

Additionally, COMPASS conducted a small (n=19) open-label study that evaluated the safety and efficacy of a single 25 mg psilocybin dose in participants with treatment-resistant depression already taking a single SSRI. Results from this trial were featured in a poster presented at the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology Annual Meeting, stating the combination was well tolerated, produced an average -14.9 point improvement in MADRS total score at Week 3 compared with baseline (comparable to the 12 point change in the Phase 2b trial), and produced similar subjective psychedelic effects. Further research is undoubtedly required to make sense of these conflicting results.

2022 also provided evidence of the 5-HT2A antagonist ketanserin’s ability to reduce the duration of the subjective effects of LSD. Earlier studies have shown that ketanserin, when given before a psychedelic, can prevent subjective effects from developing.

In 2022, however, Anna Becker and colleagues found that ketanserin, when administered one hour after LSD, reduced the total trip duration from 8.5 to 3.5 hours (Becker et al., 2022). The trip was terminated 2.5 hours after the administration of ketanserin. While this might not quite be the quick ‘trip neutraliser’ that the folks at MindMed might have been after, it’s worth noting that ketanserin may have a more favourable side effect profile when compared to other commonly used ‘trip stoppers’ such as benzodiazepines or antipsychotics.

***

While the evidence generated in 2022 contributed to our understanding of how psychedelics interact with other drugs, there’s plenty of work to be done. Not only are drug developers and researchers exploring a broader variety of psychedelics, but also a broader array of indications. This increases the drug-drug interaction possibilities, especially given that some conditions have very different first-line treatments than others.

Furthermore, it will be interesting to see if studies that aim to explore synergistic effects between psychedelics and other types of drug13, but also the effects of the co-administration of psychedelics like the recently-completed MDMA-LSD14 study conducted at University Hospital Basel (NCT04516902)15.

We should expect that 2023 will bring more drug interaction studies, such as Small Pharma’s recently initiated SSRI and DMT interaction study or Cybin’s attempt to examine the effect of SSRIs on the response to psilocybin therapy.

Neuroplasticity: Psychedelics’ Primary Mechanism of Action?

As we introduced in last year’s Review, research efforts have become increasingly concentrated on developing a greater understanding of how psychedelics elicit their apparent therapeutic effects; i.e., their mechanism of action. One of the popular working hypotheses is that psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity is the driver of therapeutic effects.

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganise and change neural pathways and connections to achieve both structural and functional changes. A gamut of drugs, including traditional antidepressants and ketamine, have been shown to induce different forms of neuroplasticity in humans (Grieco et al., 2022). Recent research suggests that psychedelics induce neuroplasticity, leading to changes in (functional) brain activity and (structural) connectivity.

As seen in 2021, much of the research on psychedelics and neuroplasticity conducted in 2022 emerged predominantly from preclinical models. These early in-vitro and in-vivo investigations shed more light on how different psychedelics can elicit changes in gene and protein expression that are indicative of neuroplastic effects (Inserra et al., 2022); stimulate (potentially) long-lasting structural plasticity through synaptogenesis or dendritogenesis (Jefferson et al., 2022); and, induce a “window of heightened neuroplasticity” that may prove propitious from a therapeutic perspective (Dwiel et al., 2022).

Though there was no significant clinical research on neuroplasticity was published in 2022, several reviews synthesised our current understanding of the concept and the potential implications of emerging preclinical research (Calder and Hassler, 2022; Grieco et al., 2022; Olson, 2022; van Elk and Yaden, 2022; Vollenweider and Smallridge, 2022).

Now, researchers might focus on measuring the functional and structural neuroplastic effects of psychedelics in the human brain. Here, neuroimaging techniques might prove to be some of the more useful tools that researchers have at their disposal. For example, hippocampal volume measured using structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may shed light on the structural neuroplastic effects of psychedelics. Longitudinal functional MRI (fMRI) studies, meanwhile, could elucidate the functional neuroplastic effects that are thought to be induced by psychedelics16.

A project that is currently underway at University College London’s Department of Psychology and Language Science appears to be taking steps towards better understanding the neuroplastic effects of psychedelics using brain imaging. The researchers explain the focus of the Understanding Neuroplasticity by Tryptamines Project, or UNITy for short, on their website, sharing:

“This will be the largest controlled study to use fMRI to ‘image’ the brain during a DMT17 trip and assess lasting changes in brain networks that underlie changes in cognition, behaviour and wellbeing. We think our results will lead to the first mechanistic understanding of the macroscopic effects of psychedelic drugs on the human brain.

While the induction of neuroplasticity has been discussed largely in reference to potential beneficial therapeutic implications, as Calder and Hassler (2022) postulate in their review:

“Neuroplasticity may not only play a role in positive long-term effects of psychedelics but also undesirable ones. Drug induced neuroplastic changes in sensory regions could conceivably be a factor in psychedelic-induced flashbacks, as well as the rarer and more severe hallucinogen persisting perceptual disorder (HPPD), in which some drug effects, including hallucinations and psychological distress, persist after the drug has been metabolised.”

It will be important to investigate the degree to which neuroplasticity is responsible not only for the beneficial effects of psychedelics, but also whether the putative mechanism contributes to the adverse effects experienced by some individuals. There are several studies (NCT03554174, NCT04630964, NCT05601648) underway using a variety of neuroimaging methods to determine whether psilocybin changes neuroplasticity in patients with depression and whether they are associated with any antidepressant effects18. Some results can be expected in 2023.

Skipping the Trip: Non-Hallucinogenic Psychedelics (Psychoplastogens)

In light of the growing body of evidence supporting the hypothesis that drug-induced neuroplasticity drives–at least in part–the therapeutic effects of psychedelics, some have begun to describe these compounds as “psychoplastogens”.

“The term ‘psychoplastogen’ was coined to distinguish compounds that produce rapid and sustained effects from those that induce plasticity following chronic administration (e.g., traditional antidepressants). By definition, psychoplastogens are therapeutics that rapidly induce neuroplasticity following a single dose leading to long-lasting changes in behavior.”

Grieco et al., 2022

Some are so confident in neuroplasticity as the mechanism of action (or, of interest) that they believe the subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary to their apparent therapeutic effects. To this end, research on so-called ‘non-hallucinogenic psychedelics’, or psychoplastogens, has emerged and accelerated over the past few years. Put simply, psychoplastogens are being developed with the aim of eliminating the acute subjective effects of ‘first generation’ psychedelics like psilocybin, LSD, and DMT while not compromising on therapeutic efficacy.

Proponents of this class of drugs have suggested that, by eliminating the subjective effects, non-hallucinogenic treatment options may prove to be more accessible, safe, and affordable than their classical psychedelic counterparts19.

Among the proponents of this endeavour is UC Davis researcher David Olson, whose company Delix Therapeutics has raised over $100m ($40 million in 2022 alone). However, competition in this space has rapidly accelerated, with a number of other companies, such as Gilgamesh Pharmaceutical and Onsero Therapeutics20, working to develop their own non-hallucinogenic candidates.

Research into non-hallucinogenic psychedelics isn’t only the remit of North American drug developers, however. In January, a Shanghai-based research group described the design of new, non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogues that displayed antidepressant-like activity in mice (Cao et al., 2022).

***

It’s important to remember that these novel psychoplastogens remain in the discovery and preclinical stages of development, with in-human trials yet to indicate their safety or efficacy (or, whether they are non-hallucinogenic in humans).

However, as Cunningham et al. (2022) pointed out, the development of non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogs is perhaps not without precedent. A compound by the name of Ariadne had previously been studied in-humans at Bristol-Myers Company, where it demonstrated some “remarkable therapeutic effects.” In spite of its promise, Ariadne’s development was eventually abandoned by Bristol-Myers21.

The compound, which is a non-hallucinogenic analog of the synthetic hallucinogen DOM (2,5-dimethoxy-4-methyl-amphetamine), reportedly produced some therapeutic benefits for patients with schizophrenia, catatonia, and Parkinson’s (ibid.).

“To date, Ariadne provides the strongest support for the therapeutic potential of non-hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists on the basis of the total available data”

Cunningham et al. (2022)

***

Some are concerned by this growing focus on non-hallucinogenic psychedelics, however. In November, Yaden et al. (2022) argued that beyond scientific or clinical uncertainties, the growing focus on developing molecules that lack the characteristic subjective effects of psychedelics might introduce some important ethical issues that should be considered as this field of research matures.

The authors argue that there are likely other benefits of the subjective psychedelic and interpersonal therapeutic experience that non-hallucinogenic compounds and treatments would be unable to reproduce. The prospect of “withholding such typically positive, meaningful, and therapeutic experiences from most patients [in favour of a psychoplastogen],” the trio contend, raises a number of ethical concerns.

“Thus, even if it is possible that nonsubjective psychedelics could bring about equivalent treatment effects in terms of measurable decrements in clinical symptoms, it is highly unlikely that they would also replicate the less-tangible, but perhaps no less important, effects on well-being derived from the human-to-human therapeutic encounter and associated sense-making of the narrative content of drug-induced subjective experiences or altered states of consciousness.”

Yaden et al. 2022

Accordingly, Yaden et al. (November 2022) argue that, in light of the valuable extra-clinical benefits of subjective psychedelic experiences, for “reasons rooted in autonomy and respect”, classical psychedelics should be offered as “the default treatment option and standard of care for those who do not have specific contraindication”. However, the authors add that patients should be permitted to choose to be treated using non-hallucinogenic alternatives should it be preferable.

Until the efficacy of classical psychedelics and non-hallucinogenic psychoplastogens are compared via clinical trials, the therapeutic utility (and, extra-clinical benefits) of the acute subjective psychedelic experience will continue to be the subject of considerable debate.

Some researchers are employing novel trial designs in an attempt to arrive at the answer of whether subjective effects are necessary faster than the time it would take novel psychoplastogens to progress to (and through) mid-stage clinical trials. Notable examples include a trial led by Boris Heifets at Stanford that was completed in 2022. The trial22 administered ketamine to half of the participating patients undergoing anaesthesia for non-cardiac surgery, and compared their depressive symptoms to those who received placebo. The unpublished results are intriguing, and discussed in further detail in our methods panel. Another inventive trial design23 sees psilocybin co-administered with midazolam, a drug that prevents patients from remembering what happened.

As we enter a new year, we might expect to see the first psychoplastogens entering in-human studies, as well as innovative trial designs such as those mentioned above providing preliminary insights into the importance (or lack thereof) of the trip24.

Beyond Psychiatry

As psychedelic research has revealed more about the mechanisms that appear to underlie their effects, researchers have begun to hypothesise ways in which these molecules might be harnessed to treat a growing list of indications. As seen throughout 2022, psychedelic research appears to be moving beyond the confines of psychiatry and into the domains of neurology, pain, immunology, inflammation, and more.

Examples of Indications Explored in Psychedelic Research Publications and (2022)

Psychiatry

- Bipolar Disorders: Bosch et al., 2022; DellaCrosse et al., 2022; Morton et al., 2022; NCT04433845; Elsayed et al., 2022; Fernandes-Nascimento et al., 2022.

- Personality Disorders: Traynor et al., 2022; Nasrallah, 2022.

- Eating Disorders: Otterman, 2022; Ledwos et al., 2022; Gukasyan et al., 2022; Fadahunsi et al., 2022; Reichelt, 2022; Williams et al., 2022; Borgland and Neyens, 2022; Peck et al., 2022.

- Behavioural Disorders: Kelmendi et al., 2022; Moreton et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2022; NCT04656301; Johnson and Letheby, 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2022; Wizla et al., 2022.

Neurology

- Schizophrenia: Wolf et al., 2022; Rajpal et al., 2022; Sapienza et al., 2022; Arnovitz et al., 2022; Mahmood et al., 2022.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder: Markopoulos et al., 2022.

- Alzheimer’s: Carvalho et al., 2022; McManus et al., 2022; Forester et al., 2022; Borbély et al., 2022.

- Cognitive Deficits: Buzzelli et al. 2022.

- Aneurysms: Ismail et al., 2022.

- Other: Webb et al., 2022; Butler et al., 2022.

Pain

- Headache Disorders: Schindler et al., 2022; Madsen et al., 2022; Rusanen et al., 2022; Schindler, 2022.

- Pain: Christie et al., 2022; Watson, 2022; Lyes et al., 2022; Hedau and Anjankar, 2022; Bonnelle et al., 2022; Dworkin et al., 2022; Ednioff et al., 2022; Meade et al., 2022; Glynos et al., 2022; Olofsen et al., 2022.

Inflammation, Immunology, etc.

- Inflammation: Burmester et al., 2022; Richardson et al., 2022; Flanagan and Nichols, 2022; Shen et al., 2022; da Silva et al., 2022; Flanagan et al., 2022; Flanagan and Nichols, 2022; Santos et al., 2022; Smedfors et al., 2022;Borbély et al., 2022; Kermanian et al., 2022.

- Immunology: Szabo et al., 2022; Katchborian-Neto et al., 2022.

- Anti-Microbial: Carrero et al., 2022.

Other

It should be noted that many of these recently postulated extra-psychiatric use cases for psychedelics are yet to be formally investigated or validated.

Some of the more intriguing applications that were discussed or investigated in 2022 include chronic spinal pain (Kelly et al., 2022), various forms of neuralgia, aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhages (Kelly et al., 2022), traumatic brain injuries (Kelly et al., 2022), connectomics (Kelly et al., 2022), anti-amoebic potential (Carrero et al., 2022; Katchborian-Neto et al., 2022), and immunological effects (Asher, 2022; Szabo et al. 2022; Katchborian-Neto et al., 2022).

Beyond hypothetical applications, clinical evidence pertaining to a number of other target indications was generated over the course of 2022.

***

Headache disorders

In 2022, two small studies that included 10 and 14 participants, respectively, were published that evaluated psychedelics as a potential treatment for cluster headaches. The first, led by Martin Madsen and colleagues (July 2022), found a significant reduction in headache attack frequency after three moderate doses of psilocybin. A second study, authored by Emmanuelle Schindler and colleagues (2022), failed to find a statistically significant reduction in attack frequency compared with placebo. However, as the authors note, these findings may be a result of the small number of participants studied in the trial.

A systematic review of retrospective surveys by Rusanen et al. (2022), meanwhile, found a “frequent and consistent high self-reported efficacy of psilocybin mushroom and LSD in prophylactic treatment of [cluster headaches].”

With six clinical trials underway, we anticipate learning much more about the therapeutic potential of psychedelic in treating headache disorders as we move into 2023 and beyond (NCT0547759; NCT04218539; NCT03806984; NCT03781128; NCT03341689; NCT02981173)

***

Inflammation

Another notable trend in research that emerged in 2022 related to the impact that psychedelics have on inflammation. Much of the current body of evidence–as discussed in articles published by Flanagan and Nichols (2022), Smedfors et al. (2022), and Nichols (2022)–points to psychedelics as a potential new class of drug, “that act on serotonergic receptors with anti-inflammatory capacity” (Smedfors et al., 2022).

Through a range of preclinical in vitro and in vivo models, researchers have found psychedelics may produce anti-inflammatory effects “at doses not only below those necessary to elicit a behavioral response, but also greatly under those associated with cardiovascular problems” (Flanagan and Nichols, 2022).

Preclinical research conducted last year by da Silva et al. (2022) focused on the possible anti-neuroinflammatory effects of psychedelics, and the relationship these effects might have with anxiolytic and antidepressant effects. Additionally, Smedfors et al. (2022) evaluated the effects of psilocybin on the release of inflammatory proteins in microglial cell lines in their study published last year.

As mentioned, much of the research conducted to-date has employed preclinical models. However, in 2022 researchers began exploring the impact psychedelics exert on markers of inflammation in healthy volunteers. One early in-human study showed a reduction in inflammation after using psilocybin, with effects lasting up to 7 days (Mason et al., 2022). However, another study, published by Burmester et al. (2022), reported no statistically significant changes when using different markers of inflammation.

While early results in healthy volunteers thus appear to be inconclusive, Burmester et al. (ibid.) suggest that, in the future, “it would be informative to directly assess the immunomodulatory effects of psilocybin in a clinical cohort characterised by heightened inflammation.”

Moving forward, Nichols (2022) points to a range of novel therapeutic applications that psychedelics, if proven to exert potent anti-inflammatory effects in humans, might have:

“If successfully translated to human disease therapeutics, psychedelics at sub-behavioural levels represent a new class of orally available anti-inflammatory with steroid-sparing properties potentially effective in several inflammatory related disease including but not limited to asthma, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.”

Establishing the Psychedelic Research Center Consortium

Written by Neşe Devenot

The first Psychedemia conference took place in 2012, at a time when Psychedelic Studies hadn’t yet formalized as an academic field. At that first conference, we advocated for the development of Psychedelic Studies as an interdisciplinary field that would integrate perspectives from across the sciences, arts, social sciences, and humanities. After ten years, the new Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education (CPDRE) held Psychedemia 2022 at The Ohio State University. Since that field is now a reality, the new conference was held to take stock of everything that happened in the last decade and to look forward to the years ahead.

Around the time that the CPDRE launched in early 2022, it seemed that new psychedelic research centers were announced every few weeks. Since so many new centers were coming online, we decided to take the opportunity to convene representatives of different centers at Psychedemia for the first Assembly of Psychedelic Research Centers. The Assembly met on the first day of the conference for a brainstorming session and reconvened the next day for the conference’s closing panel: “Charting the Future of Psychedelic Studies: An Assembly of Psychedelic Research Centers.”

Representatives from 10 centers participated, including the Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics, Mount Sinai’s Center for Psychedelic Psychotherapy and Trauma Research, The University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Psychedelic Research and Therapy, University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Transdisciplinary Center for Research in Psychoactive Substances, UCSF’s Translational Psychedelic Research Program, the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research, the University of Toronto’s Psychedelic Studies Research Program, Duke University’s Center for Integrated Psychedelic Science, the NYU Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine, and OSU’s CPDRE.

While the panel discussed the different strengths and foci of each center, recurring themes included the importance of collaboration and peer review for both research and education, especially in the context of evolving standards and best practices. Although only some of the centers include education in their mission, there was broad recognition that education and research must necessarily develop in tandem. Since psychedelics were broadly stigmatized even a few years ago, educational opportunities grounded in the findings of rigorous research must set the stage for the developing practice in the field.

After Psychedemia, the Assembly evolved into a formal Psychedelic Research Center Consortium, which convened for the first time on November 7th. A subcommittee formed to draft a mission statement for the Consortium. Although the document is still in progress, key priorities included the facilitation of institutional coordination; the development of academic integrity standards and accreditation processes; the open sharing of course objectives and curricular materials; and upholding good science communication practices. The subcommittee advocated for supporting the preregistration of quantitative research plans along with the publication of study materials and de-identified data. These open materials will allow Consortium members to analyze data within the full trial context, repeat the work others have done, complete regulatory applications, and standardize study forms according to best practices, which will help build a rigorous and interdisciplinary evidence base.

***

Members from other Centers are invited to reach out to adams.2683@osu.edu to get involved at this early stage of planning. The video from Psychedemia’s Assembly panel is available here. The Psychedemia conference will reconvene in Columbus, OH on August 8-11, 2024.

Investigating Psychedelics in Formerly Contraindicated Populations

While researchers and drug developers are increasingly considering how psychedelics might be applied beyond the realm of psychiatry, there are still plenty of overlooked, or excluded, patient populations within the study of psychedelics for psychiatric disorders. Individuals with bipolar disorder, for example, have conventionally been excluded from trials involving psychedelics.

However, in late 2022 we saw a flurry of published research on the use of psilocybin as a treatment for depression individuals diagnosed with a bipolar disorder. In early December, COMPASS Pathways announced results from a company-affiliated investigator initiated trial that looked at COMP360 psilocybin therapy as a treatment for depression in type II bipolar disorder (BD-II). The results were promising, with 12 of the 14 participants in this signal-generating open-label trial meeting the criteria for response and remission 3 months after a single psilocybin treatment.

Shortly after the results of the COMPASS-financed study were revealed, two studies were published by DellaCrosse et al. (2022) and Morton et al. (2022). Using a large-scale survey and interviews with a small subset of respondents, these studies sought to investigate the benefits and risks that were associated with self-reported psilocybin use by individuals with a bipolar subtype diagnosis. In both studies, participants reported experiencing positive benefits following their use of psilocybin, including improvements in depressive symptoms and broader mental health. Unfortunately, a number of undesirable and potentially concerning effects were also reported.

As discussed in our previous analysis, psychedelics have long been contraindicated for use in treating patients with a bipolar diagnosis or with a history of mania. Bosch et al. (2022) explain in their narrative review that this purposeful exclusion appears to stem from concerns related to the risk of psychedelics inducing switches to mania in individuals with a bipolar disorder. However, Morton et al. (2022) later revealed that these safety concerns have emerged largely as a product of anecdotal evidence and individual case studies.

Fortunately, no instances of affective switching were reported in the COMPASS-affiliated trial. Furthermore, the company announced that none of the trial’s participants experienced worsened suicidality scores. These findings are important in light of aforementioned safety concerns and the disproportionate rates of suicide amongst individuals diagnosed with BD-II.

Unfortunately, a number of undesirable and potentially concerning effects were reported by roughly one-third of participants in the survey-based study published by Morton et al. (2022). These adverse effects, which were experienced by individuals across bipolar subtypes, included worsening manic symptoms, sleep disturbances, and depressive symptoms. Similar findings were reported in the follow-up interviews conducted by DellaCrosse et al. (2022).

Thus, it remains unclear whether psychedelics may one day prove to be safe treatment options for individuals with bipolar disorders. Nevertheless, trials, like the two initiated by GH Research and the University of California, San Francisco in 2022 will continue to generate more evidence in this patient population moving forward (NCT05065294; 2021-006861-39).

Taken together, these new areas of research and in-human trials represent a gradual shift toward the investigation of psychedelics in formerly contraindicated populations25. When conducted with the appropriate safety and ethical considerations, trials in these populations are an important step toward increasing inclusion in psychedelic research.

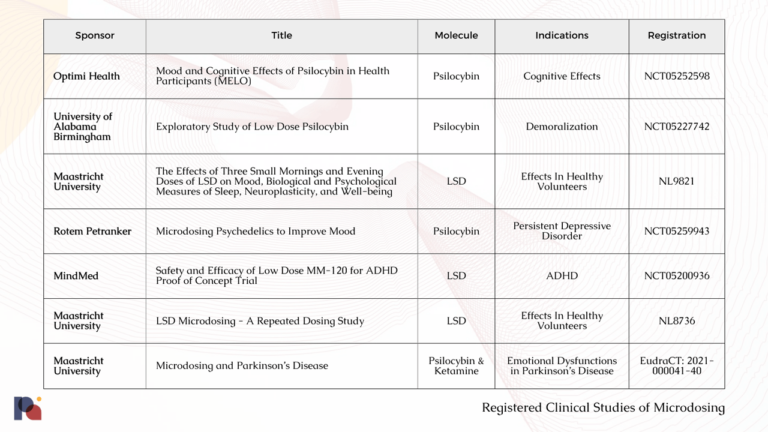

Microdosing Research Continues to Produce Mixed Results

As we discussed in our 2021 Year in Review, an increasingly large number of studies have challenged the veracity of anecdotal claims surrounding the microdosing of psychedelics, with research suggesting that expectancy effects likely drive self-reported outcomes. However, in 2021 safety concerns associated with frequent microdosing were also drawn into focus, given the potential cardiotoxic effects of chronically consuming a 5-HT2B agonist.

In spite of these negative or neutral findings, a dozen or so studies sought to evaluate microdosing in 2022. However, an observational study led by Joseph Rootman and co-authored with Paul Stamets (2022) was the microdosing study that drew the most attention in 2022. The study reported improvements in mood for those who microdosed, but failed to mention the potential role of expectancy effects. As we wrote in our earlier coverage of the study:

“Perhaps the most important thing to note here is that identifying a correlation between microdosing and better mental health does not imply that microdosing has caused a better mental state.”

Though the authors themselves did not make such a claim, the ensuing media reports on the study touted a causal relationship which, in light of the existing body of evidence, cannot be concluded.

Another survey-based study sought to investigate the effects of microdosing on, amongst other things, symptoms of ADHD (Haijen et al., 2022). Accordingly, the researchers surveyed individuals with ADHD before and after they began self-medicating with microdosing classic psychedelics.

The study reported improvements over time, hinting at causal effects, but was limited due to substantial participant attrition26. Nonetheless, the positive signal provided by this study appears to provide support for a Phase 2 proof of concept trial of low dose LSD for ADHD that was initiated by MindMed near the beginning of 2022 (NCT05200936).

However, as in 2021, a number of other studies published over the course of 2022 did not find support for popularly-reported benefits of microdosing. Included in this list of trials with lacklustre results was a double-blind placebo-controlled study conducted by Federico Cavanna and colleagues (2022).

While the researchers were able to identify changes in brain measures for those who correctly guessed if they had received a microdose, no evidence was found to support enhanced well-being, creativity or cognitive function. Other recent studies mirror these null fundings (e.g., De Wit et al., 2022; Marschall et al., 2021).

With a number of trials currently underway (see table below), we anticipate learning more about microdosing as we move through 2023. These studies will certainly bring us closer to determining whether there may in fact be any merit to the anecdotal claims of microdosing’s efficacy, and reveal more about the long term safety of the practice27.

Naturalistic Studies of Psychedelics

Data and accounts derived from naturalistic studies, surveys, case reports, and anecdotal reports have played an important role in shaping the direction of psychedelic research over the last two decades, with 2022 no exception to that trend.

Of the naturalistic research conducted last year, a survey of over 2000 people led by Charles Raison and colleagues was perhaps the most notable (Raison et al., 2022). In it, the authors report finding evidence that those who use psychedelics generally reported greater well-being and mental health. The results from the survey also highlighted the potential harms of psychedelics and the impact these adverse effects have on positive outcomes. The authors stated that, “thirteen percent of the survey sample endorsed at least one harm from psychedelic use, and these participants reported less mental health benefit.”

It also appears that the benefits associated with psychedelic use might be moderated by race and ethnicity. Through an analysis of the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Grant Jones and Matthew Nock found that white participants had lower psychological distress and suicidality when they used psilocybin and MDMA. However, this association was much smaller for ethnic minorities (Jones and Nock, 2022).

Earlier studies have demonstrated that the risks of using psychedelics are, in general, much lower than those of other drugs. In 2022, a survey of over 9,000 people conducted by Emma Kopra and colleagues found that only 1 in 500 psychedelic users sought out medical care, with the most common symptoms leading to individuals seeking care being anxiety and paranoia. The authors reported that a lack of mental preparation (mindset), a poor setting, and mixing substances were proximate causes of emergency medical care visits (Kopra et al., 2022).

Moving forward, it’s likely that digital technologies will play a greater role in the evaluation of psychedelic use outside of well-controlled clinical trials. While mobile applications like those developed by Quantified Citizen are already employed in the collection of data for naturalistic studies and research28, we expect to see more conventional healthcare data tools and repositories (such as electronic health records (EHRs) and registries) play a larger role in the analysis of real-world data should psychedelics be approved and brought to market.

Researchers and drug developers alike will look to leverage this data to identify potential safety and efficacy signals. Osmind, which describes itself as a “modern mental health EHR”, is hoping to position itself as the go-to EHR for psychedelic-assisted therapies, if approved. The company’s Vice President of Scientific Affairs, L. Alison McInnes, shared with Psychedelic Alpha that the company’s EHR, “will help uncover any adverse events related to psilocybin and MDMA when they come into broader use after FDA approval, as well as clinical characteristics of patients who are more vulnerable to them.”

Music & Psychedelics

Written by Melissa Shukuroglou

Music may have entirely different significance in an individual’s life, but one thing is universally acknowledged: music can nurture connection, both within as well as between individuals, and meaning – both of which are strongly interlinked with our psychological well-being.

It is, therefore, hardly surprising that listening to music has become a staple and valued component of psychedelic therapy. In recent years, psychedelic therapists have been utilising the findings that music engages brain areas associated with reward, emotion and memory processing and more in a therapeutic context, with the aim of facilitating emotional release and peak experiences – now thought to be predictive of the therapeutic effects of psychedelics.

Amongst the vast collection of emerging research in the psychedelic field in 2022 lies a small yet significant subset focusing specifically on music. Here are some of the highlights:

Changes in music-evoked emotion and ventral-striatal functional connectivity after psilocybin therapy for depression (Shukuroglou et al., 2022)

Adding evidence to the notion that psychedelics work with music to enhance therapeutic action, researchers at Imperial College London examined the subjective responses to music before and after psilocybin therapy in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Nineteen patients received a low oral dose (10 mg) of psilocybin, and a high dose (25 mg) one week later. fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) was performed one week prior to the first dosing session and one day after the second. Two scans were conducted on each day: one with music and one without.

Their results revealed a significant increase in music-evoked emotion following treatment with psilocybin, which correlated with reductions in anhedonia (the inability to experience pleasure in daily activities) following treatment. A reduction in nucleus accumbens (NAc; an area of the brain largely associated with musical reward) functional connectivity (FC) with areas resembling the default mode network (DMN; a group of brain regions known to be active during restful wakefulness) was also observed during music-listening (vs. no music) following treatment.

The authors claim that these results are consistent with current thinking on the role of psychedelics in enhancing music-evoked pleasure. They speculatively suggest that this could support the inference that the DMN-NAc circuit is overactive in depression, possibly suppressing NAc-mediated hedonic responses and thus accounting for the phenomenon of anhedonia. They suggest that the observed diminishment of music-induced coupling of the NAc-‘DMN’ circuit post psilocybin treatment could, therefore, reflect a correction/normalisation of this overactive inhibitory control, thus accounting for a post-treatment recovery of the normal hedonic response.

Music programming for psilocybin-assisted therapy: Guided Imagery and Music-informed perspective (Messell et al., 2022)

Copenhagen University’s Messell et al.’s work describes the process behind a new music program (the Copenhagen Music Program) designed and curated specifically for matching the intensity profile of a medium/high dose psilocybin, and suggests that an informed music choice may support the therapeutic dynamics during the acute effects of psilocybin.

The authors describe the steps behind their search, selection, and sequencing of the Copenhagen Music Program, which they share as a public Spotify playlist.

Guided Imagery and Music (GIM), a psychotherapeutic method in which the patient listens to selected classical music lasting 30-45 minutes while exploring inner imagery with verbal guiding from the therapist (Bonny, 2002; Grocke, 2019), was utilised as the therapeutic framework for choosing and sequencing music. The Taxonomy of Therapeutic Music (TTM), a music intensity rating tool developed in the field of GIM, was applied in order to systematically explore whether the music program reflected the drug intensity profile of a medium/high dose of psilocybin.

The authors discuss their findings in the context of music-psychological perspectives from the field of GIM and explore the differences between selecting music for GIM as opposed to music for a psychedelic session, and some considerations which could inform future studies.

Music is a safe, affordable and accessible tool which can be easily administered to a different range of contexts, according to an individual’s background, needs or preferences. It is certainly a thrilling time for exploring how therapeutic effects of music can be applied to psychedelic therapy; these studies are an affirmation of the potential of music as a powerful tool, as well as providing a glimpse of what the future may hold in this fascinating area of research.

***

Melissa Shukuroglou is an MRes Experimental Neuroscience graduate from Imperial College London, having previously worked with the college’s Centre for Psychedelic Research as Research Assistant. Her interest in the relationship between psychedelics and music was further solidified when she worked as Communications Manager as well as Researcher at Wavepaths, a start-up developing music technologies for psychedelic-assisted therapy. She is now interested in exploring this relationship further, and finding novel ways of leveraging the power of music in a therapeutic context.

Psychedelic-induced Belief Changes

While psychedelics have largely been investigated for their apparent therapeutic effects, the experiences brought about by these compounds also appear to reliably change one’s perspective on the world, and sometimes catalyse changes to deep-rooted beliefs.

At Johns Hopkins, Sandeep Nayak et al. (2022) investigated the belief changes brought about by psychedelics in a survey of nearly 2,400 people. Based on the survey, the researchers identified increased beliefs in dualism, non-mammal consciousness, mammal consciousness, and paranormal/spirituality. The authors reported that these belief changes endured and remained unchanged for many years after the psychedelic experience. Overall, 87% of participants expressed that their experience, “changed their fundamental conception of reality”. Additionally, the number of individuals who believed in an ultimate reality, higher power, or god increased from 29% to 59% following the psychedelic experience. This was especially true for those who had higher ratings of mystical experience. Increases in non-physicalist beliefs reported in the study included belief in reincarnation, communication with the dead, existence of consciousness after death, telepathy, and consciousness of inanimate natural objects at an individual level.

Also in 2022, Nayak–alongside Roland Griffiths–explored belief changes in the attribution of consciousness to living and nonliving entities through an analysis of survey data from 1,600 respondents (Nayak and Griffiths, 2022). Respondents displayed a large increase in the attribution of consciousness to entities ranging from non-human primates (63-83%) to plants (26-61%) and fungi (21-56%). Similarly to the aforementioned findings, those who reported a more mystical experience exhibited a greater increase in the attrition of consciousness.

Another Johns Hopkins survey-based study sought to compare psychedelic-occasioned and non-psychedelic occasioned changes in individuals’ beliefs about death (Sweeney et al., 2022). Though there were differences, both groups reported similar changes in death attitudes that they attributed to the experience, including a reduced fear of death and high ratings of positive persisting effects and personal meaning, spiritual significance, and psychological insight. Across the psychedelics, the DMT group reported stronger and more enduring experiences.

Belief changes, at least in the surveys covered here, are usually related to metaphysical or philosophical beliefs. If we broaden the concept of belief change, it can be argued that psychedelics help people adapt their beliefs away from fixed (e.g. depressed) patterns to more flexible and adaptive patterns. As seen in the section on neuroplasticity, the mechanisms for the belief changes are currently being investigated.

But, some researchers have drawn attention to the potential importance of the roles of suggestibility and one’s baseline beliefs. McGovern et al. (2022) claim, “if psychedelics change ‘beliefs’, they do so largely through experimenter suggestion and the pre-existing psychology of the individual.” The authors also draw attention to the importance of pre-existing beliefs, stating that “baseline beliefs (in the possible effects of psychedelics, for example) might color the acute effects of psychedelics as well as longer-term change.”

Psychological and Physical Safety

Through the studies published prior to and throughout 2022, an increasing amount of evidence has substantiated the view of psychedelics as being relatively safe and well-tolerated drugs. Nonetheless, common adverse effects are often reported, such as headaches, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and more (Goodwin et al., 2022). However, these effects tend to be transient in nature and, as a result, don’t often persist beyond the acute psychedelic experience.

There are also some physical safety concerns that many researchers agree warrant further study. These include risks related to the cardiovascular effects that various psychedelics might precipitate, such as their impact on blood pressure or the potential longer-term cardiotoxic effects of chronic 5-HT2B agonism, for example.

Despite the large number of promising results that have recently been published on the safety and tolerability of psychedelics in humans, Bouso et al. (2022) suggest that the careful selection of trial participants may reduce the probability that serious negative effects are experienced and thus reported. Furthermore, the small sample sizes used in many early-stage trials might make it challenging for researchers to identify some of the potentially less common–but nonetheless serious–adverse effects.

Accordingly, Johnston et al. (2022) argued that more needs to be done to research the potential adverse effects of psychedelics in older adults who frequently suffer from potentially relevant comorbid conditions like cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, the frequency of polypharmacy in this older population introduces safety concerns related to important interactions between psychedelics and commonly prescribed medications. These considerations speak to the need for more DDI studies in the near future.

However, as numerous researchers have noted, many of the reported adverse effects of psychedelics (especially psychological risks and adverse events) might often be the result of poor controls over contextual factors. For example, in their review, Schlag et al. (2022) state that:

“medical risks are often minimal, and that many – albeit not all – of the persistent negative perceptions of psychological risks are unsupported by the currently available scientific evidence, with the majority of reported adverse effects not being observed in a regulated and/or medical context.”

These findings point to the commonly-understood need to manage elements of set and setting, as well as train professionals to manage adverse events as they emerge. Speaking on the safe introduction of PAT in Canada, Mocanu et al. (2022) suggest that several factors should be considered: formal training of therapists should be expanded; practice standards should be formed; and, rigorous monitoring of clinical outcomes implemented. In other words, they argue that capacities need to be built that mirror those in other healthcare professions29.

As discussed in our earlier section on therapeutic alliance, therapists (or other facilitators) often play an integral role in the administration of psychedelic-assisted therapies. A study published by Hendrick et al. (2022) found that trial participants who had received LSD attributed their “feelings of safety”, in part, to the support of the attendants (study personnel). Findings such as this appear to reinforce the need to establish a strong therapeutic alliance, not only to improve clinical outcomes, but also to ensure a patient’s safety.

However, it is also important to note that psychedelics are more often than not taken outside of well-controlled, clinical settings. As a result, it is also necessary, and likely valuable, to evaluate the safety of these drugs in more naturalistic, less-controlled contexts.

To this end, in 2022 Bouso et al. (2022) published the results from the Global Ayahuasca Survey, where the authors explored the risks and benefits of ayahuasca use using data from the responses of nearly 11,000 participants.

While adverse physical and mental health effects were frequently reported, the authors note that many of these effects were transient in nature, and that the majority of the adverse effects reported could be considered as “normal effects of ayahuasca use”. Medical attention was found to be required in 2.3% of cases where individuals reported experiencing adverse physical effects.

Adverse mental health effects experienced in the weeks and months following the ayahuasca experience were reported by 55.9% of respondents, with 12% seeking out professional support as a result. However, the researchers also reported that roughly 88% of respondents considered their adverse mental health effects to be, “part of a positive process of growth or integration”.

In line with previous findings, the researchers wrote that, “both adverse physical and mental health effects were significantly associated with non-supervised and non-traditional supervised contexts.” Nonetheless, some relevant and important findings that may warrant future investigations were identified through this large-scale study. Two examples were the low, but notable, percentage of respondents who reported experiencing fainting (4.1%) and fits or seizures (1.3%).

However, as Belouin et al. (2022) explain, “many of the risks associated with psychedelics come not so much from the physiological effects of the drugs themselves, but from how and with whom they are used.” Accordingly, in light of recent revelations surrounding transgressions on the part of providers, some articles published in 2022 raised concerns over patient safety and vulnerability while under the influence of psychedelics (Belouin et al., 2022; Mintz et al., 2022; Earleywine et al., 2022).

Diversity in Psychedelic Clinical Trials

As clinical development programs mature, an increasing number of trial participants are being administered psychedelics in hope of turning these compounds into approved treatment options. Since research into psychedelic was renewed in the early 2000s, that number of study participants has grown into the multiple thousands.

However, as Hadar et al. (2022) explained in their bibliometric analysis, published in January 2022, there is a notable lack of diversity in psychedelic research. In turn, the limited heterogeneity of study participant pools has seemingly left non-WEIRD (western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic) populations excluded from this burgeoning field of research. Some have suggested that, besides being unethical, this lack of trial diversity reduces the generalizability of study results (Ledwos et al., 2022), especially given the fact that marginalised populations are more likely to be exposed to trauma.

In our own analysis of 24 studies that included published demographic data on over 1000 participants, we found that 85% of trial participants were white. These findings are similar to those reported in an earlier publication from Michaels et al. (2018), which reported that 82.3% of trial participants included in screened psychedelic studies were non-Hispanic White, and fewer than 3% were African American.

While these demographic statistics paint a less-than-inclusive picture, through our analysis of 49 studies that published data on participant sex, we found a very balanced distribution.

In an effort to address this lack of participant diversity, some researchers have argued for the use of “focused recruitment” to ensure more representative or inclusive trial samples (Ortiz et al., 2022). Other proposals include working towards greater diversity and representation amongst facilitators and therapists, for example.

One group that has, more recently, worked to address the lack of diversity in clinical studies is MAPS PBC. Its recently-completed second Phase 3 trial of MDMA-AT for PTSD saw participants of colour represented more than 50% of the total study participants30.

Another dimension that is perhaps less often discussed is that, in many studies, trial participants are on average more highly educated than the general public. Take, for example, the Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression led by Carhart-Harris et al. (2021), where 76% of participants enrolled in the study had a university-level education31. This number is notably higher than the 57% reported in the United Kingdom, and 47% across OECD countries in 2021.

Revisiting MDMA-Assisted Therapy Data

The stellar results reported in MAPS’ Phase 2 and 332 trials of MDMA-AT for PTSD have garnered a substantial amount of attention. However, PTSD is not the only potential therapeutic application for MDMA that MAPS has been investigating. In fact, last year the non-profit published results from three studies on chronic pain, substance use disorders, and eating disorders.

Drawing on data reported by a subset of participants in one of its Phase 2 studies, Christie et al. (2022) report notable reductions in chronic pain, as measured by pain intensity and disability scores. Of the 32 participants included in the analysis, 24 had reported disabilities related to their chronic pain. After receiving MDMA-AT for PTSD, those with moderate and severe pain reported lower scores.

Using data from the first Phase 3 study (MAPP1), Nicholas et al. (2022) found significant decreases in Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) scores. However, the researchers were unable to identify changes in a similar measure of substance use disorders. It is worth noting that prospective participants were excluded from the trial if they had pre-existing alcohol or substance use disorders (Mitchell et al., 2021). This signal, coupled with the findings from an early study by Sessa et al. (2021), should encourage studies of MDMA-AT for alcohol use disorder.

A third analysis also examined data from MAPS’ first Phase 3 trial and found significantly lower scores on a test of eating disorders following MDMA-AT. Brewerton et al. (2022) reported that, at the start of the study, 15% and 31% respectively had clinical and high-risk scores on the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT). Among participants who completed the study, EAT scores were significantly reduced when compared to baseline. These findings appear to warrant the growing focus placed on investigating psychedelics as treatments for eating disorders.

These results paint a picture of the breadth of potential therapeutic uses of MDMA-AT, which appear to extend well beyond PTSD into other psychiatric indications and domains such as the treatment of chronic pain and eating disorders. It will be interesting to see if these findings, which are currently measured in the order of weeks and months, are durable over time.

Perceptions of Pyschedelic-Assisted Therapies

As psychedelics progress through later-stage trials and potential commercialisation, an increasing amount of effort will be directed towards understanding the perceptions of medical professionals. Without buy-in and trust from these stakeholders, patient access to even the most effective new therapies may be limited.

Accordingly, over the course of 2022, seven studies investigated the attitudes of various types of healthcare providers towards psychedelics. Providers surveyed included psychiatrists (Levin et al., 2022; Wright et al., 2022) counsellors (Hearn et al., 2022), psychologists (Luoma et al., 2022; Meir et al., 2022; Meyer et al., 2022; Wright et al., 2022), and practitioners working in palliative care (Reynolds et al., 2022).

Results from many of the studies indicate that healthcare providers often felt receptive or neutral towards the use of psychedelics. However, a survey conducted by Wright et al., (2022) found that Australian psychiatrists reported a greater level of hesitancy than psychologists in recommending trials of MDMA-AT. Furthermore, the researchers note that more experienced health professionals appear to have less favourable views of MDMA-AT trials than their less-experienced counterparts.

Responses also suggested that these professionals have, in many cases, limited knowledge of the current body of evidence. As a result, while many respondents acknowledged the potential of these emerging treatments, they also frequently reported the need for more evidence to be generated.

In light of ongoing debates related to the basis for the harsh scheduling of psychedelic compounds given their purportedly low abuse potential, therapeutic effects, and safety, Levin et al. (2022) conducted a survey to understand whether or not American psychiatrists believed that the current drug scheduling of psilocybin and ketamine was “scientifically coherent.” Following the study, the authors conclude that:

“American psychiatrists’s perceptions about safety and abuse/therapeutic potential associated with certain psychoactive drugs were inconsistent with those indicated by their placement in drug schedules. These findings add to a growing consensus among experts that the current drug policy is not scientifically coherent.”

While the perceptions of professionals will be important to the success of any approved psychedelic therapy, so too are the attitudes of individuals who may one day be eligible patients. However, over the course of 2022 only one study sought to investigate perception amongst this potential patient population. In their study, Gray et al. (2022) surveyed 21 veterans and active military service members in an attempt to understand beliefs and perceived barriers towards psychedelic-assisted therapies (PAT). The authors found that perceptions of PAT amongst participants improved following psychoeducation, with many reporting that they would support PAT should it prove efficacious. However, fears of personality changes, long-term effects, and traumatic brain injury complications were frequently reported in the survey.

In light of existing drug prohibition laws and stigmatisation of psychedelic (and broader drug) use, population-level receptivity will certainly be an important consideration moving forward. Accordingly, last year Žuljević et al. (2022) developed and validated an instrument that can be used to assess and measure attitudes towards psychedelics amongst the general population.

Similar efforts will surely be made to educate, market, and spread awareness of PAT as companies with more mature development programs work towards drug approvals and commercialisation. See our Approvals to Access section for more on this topic.

Part of our Year in Review series

This content is part of our 2022 Year in Review, which looks back at the past year through commentary and analysis, interviews and guest contributions.

Receive New Sections in Your Inbox

To receive future sections of the Review in your inbox, join our newsletter…

- This study’s active arm administered two 25mg doses of psilocybin with talk therapy. Specifically, the study used the Accept-Connect-Embody (ACE) framework adapted from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT, which evolved from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)).

- Such as Ardito and Rabellino, 2011.

- The authors wrote: “C-PTSD needs a larger number of psychedelic experiences in contrast to PTSD resulting from a single trauma. In this model, MDMA was most often used in the first phase to enhance motivation to change, and strengthen the therapeutic alliance, allowing it to become more resilient, stress-relieved and less ambivalent. When emotional self-regulation, negative self-perception and structural dissociation had also begun to improve and trauma exposure was better tolerated, LSD was introduced to intensify and deepen the therapeutic process.” (Oehen and Gasser, 2022: 1).

- Presented as a poster at ACNP 2022.

- Finnish psychology researcher Samuli Kangaslampi shared on Twitter that the therapeutic outcome involved in the analysis was, curiously, the “level of, not change in, depression” thus limiting the ability to identify what factors are associated with a reduction in depression scores.

- A COMPASS representative told Psychedelic Alpha: “Patient safety is of utmost importance to us”, and that the company’s psychological support is “non-directive - its main purpose is to prepare patients to be open to all experiences that come their way after taking a dose of COMP360 psilocybin.”

MAPS’ Manual for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (available online) allows for a multiplicity of methods and disciplines to be invoked, such as holotropic breathwork.

- The authors looked at literature published between 1958 (the first synthesis of psilocybin) and December 2020.

- Elsewhere, researchers affiliated with MAPS PBC used the FAERS database to report cases of serotonin syndrome in MDMA users. While the database has many flaws, it remains a useful tool. See Makunts et al., 2022.

- See Bonson et al. (1996), for example.

- Gukasyan et al’s new findings stand in contrast to a study led by Anna Becker and colleagues at the University of Basel in 2021 (and, as such, outside of the scope of this Report). There, researchers found that a two week treatment of escitalopram (10 mg for the first week, 20 mg for the second week) did not change the positive effects of a high dose of psilocybin in healthy volunteers. Instead of a dampening effect, this trial found a reduction in only bad drug effects, and a reduction in adverse cardiovascular effects (Becker et al., 2021). It should be noted that this study was conducted with healthy volunteers and that two weeks of antidepressant treatment is insufficient to model the neural changes that take place with more typical long term use, limiting the generalizability of this study’s results.

- An important caveat to their analysis is that it included antidepressants as well as antipsychotics. Certain antipsychotics (e.g. aripiprazole, quetiapine) may be used as adjunctive medications in difficult-to-treat depression, however their action as 5-HT2A antagonists could potentially impact 5-HT2A receptor changes differently than reuptake inhibitor antidepressant (e.g. SSRIs) tapering.

- Take, for instance, the 2022 approval of Auvelity, a dextromethorphan/bupropion combination medication for the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Might psychedelic drug developers look to adopt this playbook to improve a candidate molecule’s pharmacokinetics?

- Known colloquially as “candyflipping”.

- Another possibility is the sequential administration of various psychedelics, as seen in The Mission Within’s protocol, described in Davis et al. (2020).

- See Knudsen (2022) for a more detailed discussion on brain imaging and neuroplasticity.

- Small Pharma announced that they would be providing DMT for the University College London’s UNITy project

- No other therapeutic indication is currently being looked at in the context of neuroplastic changes induced by a psychedelic - might any association(s) be indication-specific?

- See Peterson and Sisti’s Commentary in the Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics (2022), for example.

- Which counts UNC’s Bryan Roth as a scientific co-founder.

- It should be noted Ariadne is a potent 5-HT2B agonist. Chronic agonism of this receptor has been linked to valvular heart disease, with drugs like Pergolide withdrawn from the U.S. market for this reason.

- Intraoperative Ketamine Versus Saline in Depressed Patients Undergoing Anesthesia for Non-cardiac Surgery (NCT03861988).

- Pilot RECAP Study in Healthy Volunteers (RECAP) (NCT04842045).

- Note: While some companies are working to skip the trip, others are looking to keep the trip but drop the drug. For companies like TRIPP, the benefits enabled by a different kind of plastic–virtual reality headsets–might help people realise well-being benefits by generating self-transcendent experiences like those experienced on psychedelics. A study published in 2022 suggests the company may be on to something (Glowacki et al., 2022). VR is also being harnessed by companies like Enosis Therapeutics, who hope to integrate four VR scenarios into the psychedelic-assisted therapy protocol.

- One other example is a University of Chicago study (in collaboration with the Usona Institute) launched in 2022, which will study psilocybin in co-occurring MDD and Borderline Personality Disorder (NCT05399498). Another study, from Johns Hopkins, is recruiting for a trial of psilocybin for depression in people with mild cognitive impairment or early Alzheimer’s disease (NCT04123314).

- Only 1 in 5 who completed the first survey filled in the final one.

- See slides submitted to an NIH workshop by Dr. Bryan Roth on the topic of psychedelics and 5-HT2B toxicity

- For more commentary on the utility of real-world data, see a relevant publication from Carhart-Harris et al. (2021).

- See also Belouin et al. (2022).

- Early analysis of the Phase 2 and Phase 3 studies by Ching et al. (2022) finds that Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) participants experienced similar improvements to PTSD measures compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts.

- Also, 82% of respondents to a survey conducted by Morton et al. (2022) were university/college educated.

- Full results have only been published from the first of MAPS’ two Phase 3 trials (Mitchell et al., 2021).