This Week:

- ⚖️ Mass. Bill Would Limit MDMA Therapy Price to $5,000 per “Treatment Service Unit”; But Is It Misguided?

- 💸 Empyrean Neuroscience Loses CEO and CMO

- 🏦 Quick Take: Pear Therapeutics Files for Bankruptcy Citing Lack of Payor Buy-in

- 📓 Yale Psilocybin Study’s Lukewarm Results Suggest Complex Role of Expectancy

- 🎲 Angermayer Increases Stake in atai

- 📄 Dutch Government Forms MDMA Commission; NIH Forms Psychedelics Interest Group

and lots more…

Psychedelic Sector News

Mass. Bill Would Limit MDMA Therapy Price to $5,000 per “Treatment Service Unit”; But Is It Misguided?

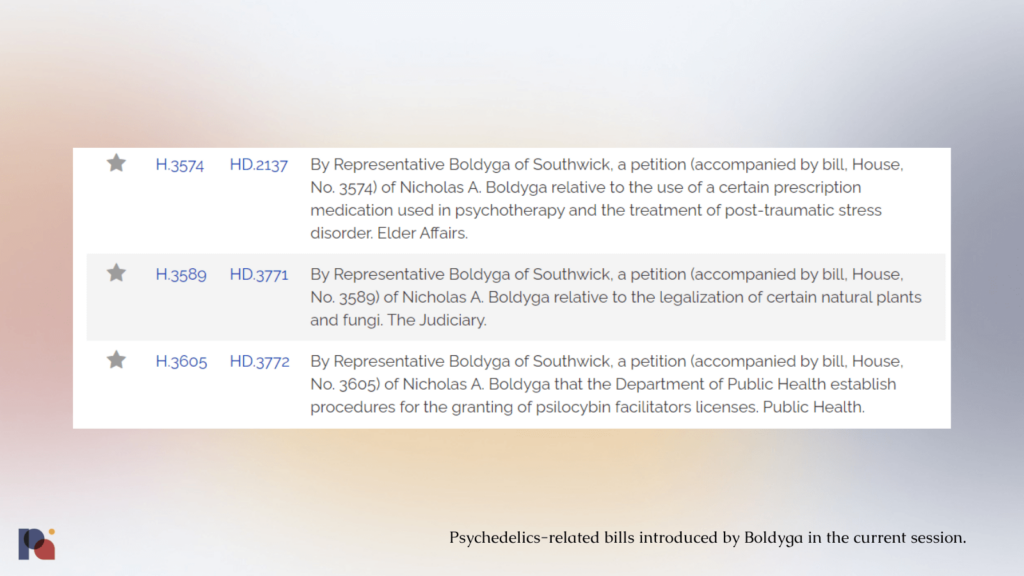

Republican Representative and former police officer Nicholas Boldyga has introduced a trio of psychedelics-related bills to the Massachusetts House.

One such House Bill, H 3574, proposes the addition of the following subsection to the state’s General Laws:

(j) Any person or entity registered to prescribe, manufacture, distribute, dispense or provide services related to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) shall not charge more than $5,000 per MDMA treatment service unit. For the purposes of this subsection, “MDMA treatment service unit” shall mean any prescribed and controlled administration of MDMA in any 7-day consecutive period including therapy and related counseling.

This would be effective if and when MDMA is approved as a prescription drug by the FDA, at which point the Bill would automatically reschedule the approved therapy in the state.

The handful of psychedelic news outlets that have picked up on the Bill have been largely supportive.

Microdose’s short piece reports that “it’s a sign that legislators (and a Republican at that) are taking the future of psychedelic medicine access seriously.”

Psychedelic Spotlight, meanwhile, invokes the broader therapist shortage, arguing that without such a price cap MDMA-assisted therapy might present a “lucrative opportunity” to mental health practitioners that could create further drain on dwindling human capital:

“This monopoly also has critical implications for the mental healthcare system beyond MDMA. This is because the lucrative opportunity to charge these prices to high-income clients is leading many therapists to leave their practices that serve low and middle income residents at a time when Massachusetts already has a critical shortage of therapists.”

Despite Psychedelic Spotlight reporting that this is happening in the present tense, it’s not clear that this is the case. Nor is it likely, in our opinion, that this supposed psychedelic rent-seeking behaviour among therapists will be a significant phenomenon if a psychedelic-assisted therapy is approved.

Most psychedelic-assisted therapists we speak to remind us of how difficult the work is, with lengthy sessions of around eight hours during MDMA dosing sessions meaning that most facilitators would limit their psychedelic practice to a couple of sessions per week.

There’s also no reason to believe that psychedelic-assisted therapy would be any more lucrative for Massachusetts-based therapists than practising more conventional therapy: the average cost of a therapy session in MA is just over $190, according to Zencare.

Let’s assume that an MDMA treatment session is 8 hours, and two 90-minute preparatory or integrative sessions fall within the 7-day period contemplated by H 3574. That’s 11 hours of therapy, and all of this involves two therapists. According to Zencare’s data, that’s an opportunity cost of $2,090 per therapist, or $4,180 between the therapist pair.

Now imagine what other costs and complexities may be involved in the delivery of MDMA-assisted therapy in a regulated context such as additional personnel (oversight of a psychiatrist, for example), the cost of the physical space in which the therapy takes place, and the cost of the MDMA: which will of course include some mark-up on MAPS PBC’s part.

Given these facts, it’s very difficult to reconcile the purported rationale of this Bill with reality. If a therapist were drawn toward the most “lucrative” opportunities, surely they would set up private practice in a city like Boston and charge over $200 per conventional therapy session?

It feels like this cash cow (or, psychedelic strawman) has been dreamed up by a policymaker who is conflating the types of mental health professional that might deliver MDMA-assisted therapy with the types of operators and practitioners found at luxe retreats and other wellness-type clinics.

There is no arguing whether cost will be an issue: it will (see our From Approvals to Access coverage for more on this topic). But, artificially fixing the cost of MDMA-assisted therapy is likely misguided. The sticker price ‘affordability’ of a drug does not ensure access, especially given the immense labour intensity of psychedelic-assisted therapies where the cost of therapists’ time is the bulk of the outlay.

We might do better by focusing on engaging with payors to ensure reimbursement as broadly as possible, as well as working out how we will incentivise would-be psychedelic therapists to take the direct and opportunity costs of re-training and engaging in a challenging new modality; rather than cynically and baselessly painting MDMA-AT as a cash cow.

‘Access’ requires willing and capable providers, too.

It’s also worth keeping Boldyga’s politics in mind when considering his rationale for forwarding this Bill.

Boldyga is a proponent of economic liberty, having worked with libertarian groups to roll-back pandemic-era restrictions and sitting as the State Chairman of ALEC, one of the most prominent conservative free-market forums.

When it comes to healthcare policy, ALEC generally advocates for deregulation and the promotion of market-based developments, such as the privatisation of Medicare and Medicaid and staunch opposition of the Affordable Care Act. Boldyga himself has consistently voted to defund and reduce coverage by MassHealth, the state’s Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program.

As such, despite couching his MDMA-assisted therapy price fixing bill in concerns over accessibility, Boldyga has done little to address issues of accessibility to healthcare in his political career. In fact, many would argue he has shrunk access to healthcare for the most needy in Massachusetts.

Empyrean Neuroscience Loses CEO and CMO

New York and Cambridge-based Empyrean Neuroscience launched in late 2022 with a $22m Series A round to fund its efforts to “genetically engineer small molecule therapeutics from fungi and plants”. The funding was led by a private investment group, ‘Spore Partners’.

Put simply, the company hopes to identify drug candidates by making genomic modifications to known species of fungi and plants such as Psilocybe cubensis, Tabernanthe iboga, and Cannabis sativa.

In contrast to many other drug developers working with synthetic or isolated formulations of pure psilocybin, Empyrean intends to develop treatments using entire psilocybin-containing mushrooms. The company has suggested that this approach may allow it to leverage an entourage effect resulting from synergies with other constituents naturally produced by the fungus. However, it remains unclear whether these resulting effects could produce a superior therapeutic benefit compared to isolated forms of psilocybin. (See our more detailed write-up of the company for more.)

But, it appears Empyrean’s C-suite is bailing.

In a Press Release that announced Dr. Fred Grossman’s appointment to Reunion Neuroscience’s Board of Directors, Grossman was described as having “previously served as the Chief Medical Officer at Empyrean Neuroscience”; past tense.

Empyrean’s CEO, meanwhile, updated his LinkedIn entry for that position with an end date: February 2023.

It appears, then, that just half a year after announcing their launch, Empyrean is having some sort of difficulties.

Quick Take: Pear Therapeutics Files for Bankruptcy Citing Lack of Payor Buy-in

On Friday, digital therapeutics company Pear Therapeutics filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy, announcing that it would lay-off 92% of its workforce as it seeks a buyer of its assets.

It’s a significant fall from grace for the trailblazing company, which received FDA approval for the first prescription digital therapeutic on the market when its reSET application designed to treat substance use disorders was approved in 2017.

Despite this approval and the purported buy-in from prescribers and patients, “that isn’t enough”, CEO Corey McCann wrote on LinkedIn when announcing the bankruptcy filing. Pear’s digital therapeutics appeared on over 45,000 prescriptions in 2022, but only around one half of those were filled and Pear collected payment on just 41% of those. The company made a $123m loss in 2022, with revenue just under $13m.

McCann continued, “payors have the ability to deny payment for therapies that are clinically necessary, effective, and cost-saving”, implying that reimbursement for the novel treatment paradigm was the Achilles heel for the company, which was founded in 2013. Indeed, while some health insurers including a small number of state Medicaid programs have paid for prescription digital therapeutics, Medicare doesn’t.

Pear’s apparent inability to get payors on board is a good reminder of the challenge ahead for psychedelic-assisted therapies, which are much more resource-intensive than an app.

Angermayer Increases Stake in atai

Last week, atai Life Sciences co-founder and Chairman Christian Angermayer shared (via LinkedIn) 14 reasons why I am increasing my stake in atai Life Sciences.

In his address to ‘fellow shareholders’, Angermayer acknowledged the headwinds facing the biotech sector, telling readers that “I know this is unpleasant and frustrating”. But, Angermayer believes this “pain” being felt in the markets “also creates an opportunity”, arguing that shares in his company “have never been more attractive”.

Chief among his reasons for believing in atai are its cash position, pipeline and patents. On this latter point, Angermayer’s opinion is that “atai and COMPASS together are clear market leaders”. Later in the piece he mentions the company’s digital therapeutics work, explaining that “atai has a bold vision of owning the entire mental health journey”. He dismissed the majority of psychedelics companies as having “no real business model”, claiming that there are “just a handful” of companies with a “real, viable strategy”.

Elsewhere, Angermayer conceded that the PCN-101 results are “disappointing” and a ‘setback’ (see our analysis), but says “it is not the end of the world”, pointing out that Janssen’s Spravato product also failed in a couple of Phase 3 trials (see our Dispatch from ECNP for more on this).

Through his family office, Angermayer purchased just over 1.2 million shares in the company at a price of $1.318 per share, bringing his total ownership to over 32 million shares. The company’s CEO, Florian Brand, also purchased ATAI shares at the end of March. SEC filings show that Brand acquired 70,000 shares in the company at a weighted average price of $1.4794, implying an aggregate outlay of just over $100,000.

The company’s share price reacted positively to the news, gaining around 20% since last month, but still down around 65% over 12 months.

Featured Psychedelic Jobs

- Patent Agent at Calyx Law.

- Clinical Study Coordinator at Journey Colab.

Browse more roles and get more job posts to your inbox by signing up for alerts here. Make an account to join our free talent pool, too.

Miscellaneous News

Yale Psilocybin Study’s Lukewarm Results Suggest Complex Role of Expectancy

A new study from a group of Yale researchers (Sloshower et al., 2023) evaluates psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder (MDD). Here, we take a look at the trial’s design and headline findings…

Participants

The study enrolled 22 participants, with 15 completing both the placebo and psilocybin dosing sessions. Participants had suffered from depression for a mean average of two decades, and must have failed at least one antidepressant trial during their current depressive episode.

Participants need not be entirely psychedelic naive, but exposure to psilocybin in the past year was an exclusion criterion. Indeed, 42% of participants (n = 8) had prior exposure to psychedelic drugs, but not within a minimum of three years prior to enrolment.

Methodology

Before we discuss the methodology of this trial, it’s important to note that the study was primarily designed and powered “to investigate electrophysiological indices of neural plasticity in depressed individuals.” (This publication shares the therapeutic results of the study, while the neurobiological and psychological mechanisms of action will be reported elsewhere in due course.)

Interestingly, the trial protocol sought to incorporate principles of a specific evidence-based therapy for depression, in this case Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), in a “semi-structured, manualized fashion”.

While other researchers have suggested that ACT be used in psychedelic research (e.g., Luoma et al., 2019; and, the authors of the present study discussed their rationale for employing ACT in Sloshower et al., 2020) and some psychedelic trials have incorporated elements of the psychotherapeutic approach (e.g. ‘psychological support’ used in Carhart-Harris et al., 2021 and Goodwin et al., 2022), the present trial is the first to employ ACT specifically.

The authors believe that employing a “delineated therapeutic framework and treatment manual theoretically improved consistency in therapeutic approach across participants and between study therapists.”

But, importantly, the researchers didn’t measure adherence to this protocol during the study.

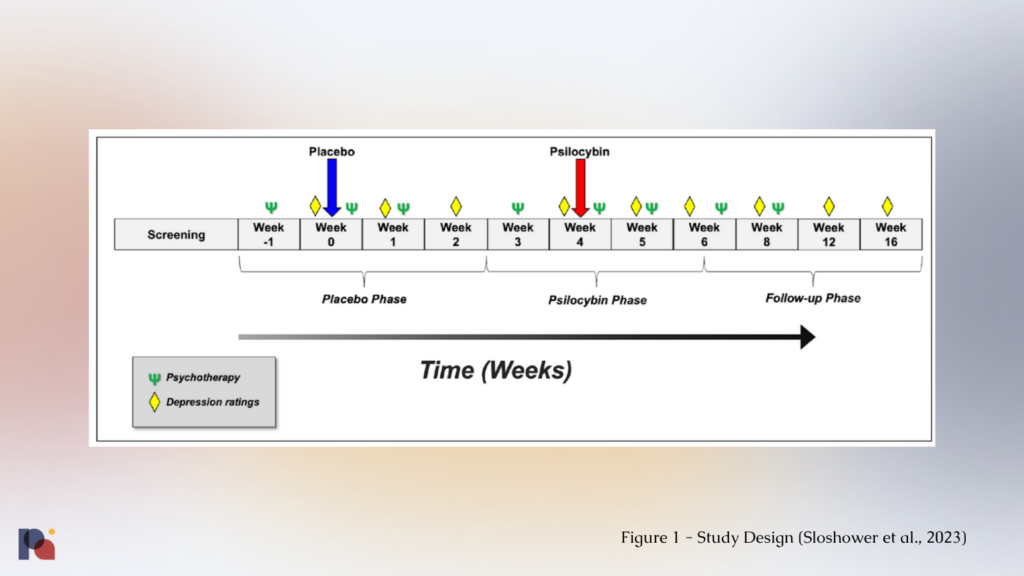

The study saw participants receive a placebo dose first, followed by psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg1, up to 35 mg) spaced four weeks apart. This within-subject design increases statistical power, meaning researchers might be able to generate a statistically significant finding with a smaller sample size than in a between-subjects design comparing a placebo arm to one with psilocybin.

In an attempt to enhance blinding and minimise expectancy, both participants and study staff recruiting and conducting study assessments and ratings were told participants would receive two of three possible dose conditions (placebo, low-dose psilocybin (0.1 mg/kg) and moderate-dose psilocybin (0.3 mg/kg)) in random order, when in fact the low-dose psilocybin would not be administered In an attempt to further minimise expectancy, the effects of the low-dose were explained ambiguously and that sensitivity to psilocybin varies across individuals.

However, 79% and 80% of participants2correctly guessed the placebo and psilocybin doses, respectively. It’s fair to say, then, that these ‘enhanced’ blinding procedures weren’t effective in this trial.

These attempts would likely have been more successful, by the authors’ own admission, if used in a psychedelic-naive population. The authors explained that they only excluded this with exposure to psilocybin in the past year in order to “maximize feasibility”. Might this suggest that it’s becoming difficult to find eligible MDD patients who haven’t tried psilocybin?!

In terms of prep and integration, the study had an eight session psychotherapy protocol delivered by a psychiatrist and a study therapist. A single two-hour prep session was delivered before each dosing session, with two one-hour integration sessions conducted one day and one week after each dosing session, and two additional one-hour integration sessions provided after the primary outcome measures were collected at week 6.

Interestingly, the authors report in the supplemental materials that the study “paired one therapist with a psychiatrist who was also present for all drug dosing sessions and took part in most preparatory and debriefing sessions”. This suggests that at some points in the study, there could have been a 1:1 patient:therapist ratio.

Results

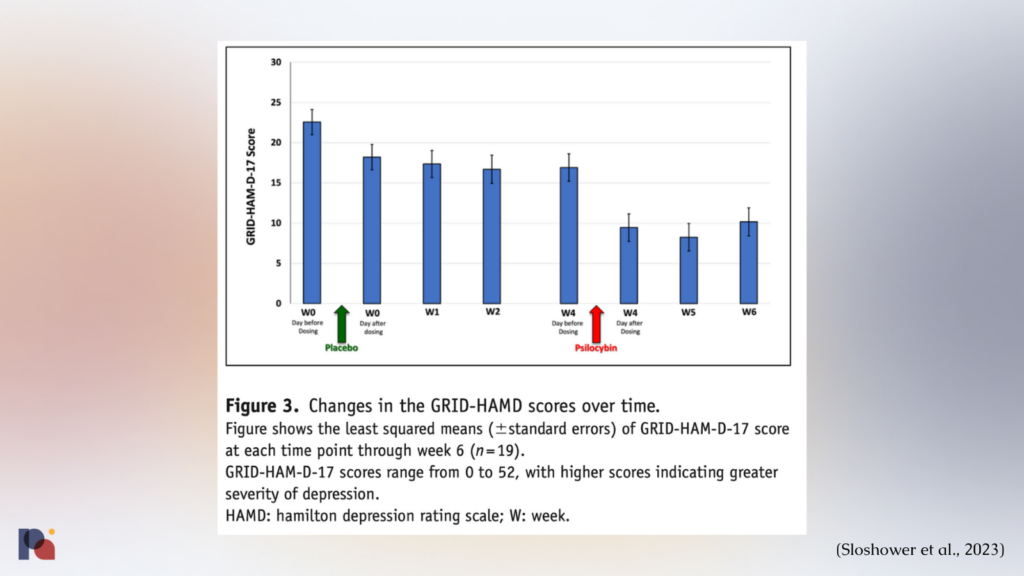

The study ultimately found that psilocybin was no better (at least in a statistically significant manner) than placebo in reducing depression in participants.

“Mean decreases in depression scores [GRID-HAM-D-17] were greater during the 2-week period after psilocybin (Δ = 6.3–8.7) than after placebo (Δ = 4.4–5.8); however, the difference was not statistically significant”

This lack of significance in the primary outcome could be due to the small sample size (n = 15), as well as potential carryover effects from the placebo session3.

Interestingly, participants’ maximum score on the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) was negatively correlated with change in depression scores one day and two weeks post-placebo session. As such, it could be the case that participants who thought they had received a psilocybin dose in the first session (which was in fact placebo) fared worse, which is the opposite of what we might expect in a placebo response.

The authors explain what appears to be complex interplay between “expectancy, therapy effects and drug/placebo effects” in psychedelic trials:

“Most participants expressed disappointment in not having received the higher psilocybin dose in that first session, the majority remained hopeful that they would receive it in the second dosing session. In that context, participants generally engaged meaningfully in the psychotherapy during the placebo phase as they anticipated the next dosing session.Thus, the psychotherapy and nonpharmacological interventions that participants received throughout the placebo phase, along with positive expectations toward the upcoming second dosing session, likely contributed significantly to the clinical improvements observed in the weeks following the placebo session. Similarly, positive expectancy effects and functional unblinding during the psilocybin dosing session could have also contributed to the improvements observed in the period after the psilocybin dosing session. Clearly, the significant clinical improvements observed throughout the course of this study suggest a complex interplay between expectancy, therapy effects, and drug/placebo effects in studies of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.”

Future research directions

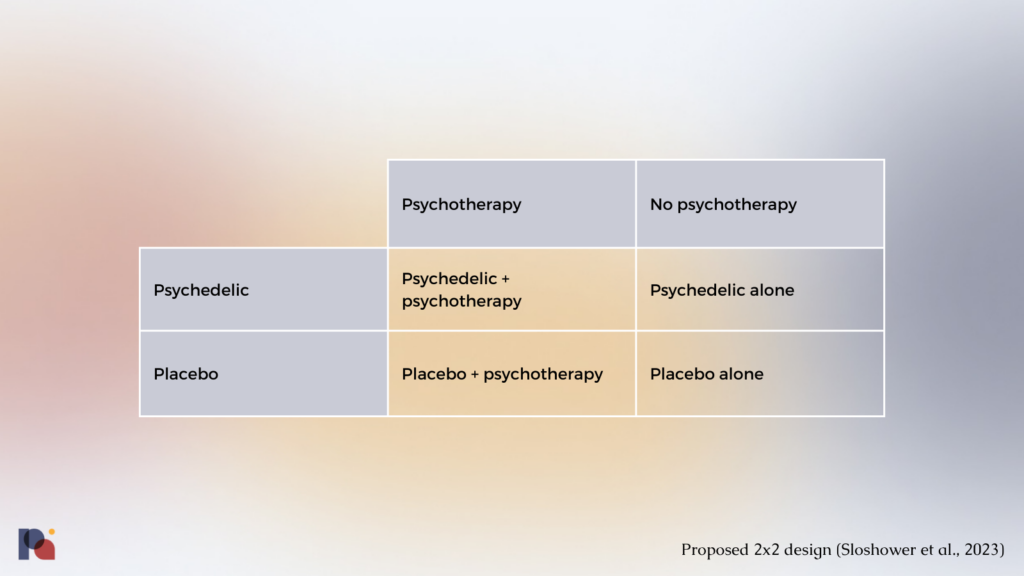

The authors suggested that future research might benefit from including a parallel group or 2×2 design, as such:

This design would better control for the role of therapy, expectancy and carryover effects between treatments; allowing us to better appreciate the relative contributions of each element of the protocol.

Recent media on the same topic

In our latest Opinions piece, Clerkenwell Health’s Arda Ozcubukcu discusses the potential value that could be derived from a greater focus on the use of evidence-based psychotherapies (such as ACT) in psychedelic research and practice. Arda shares how such an approach may support efforts to prove cost-effectiveness, enable psychedelics to be more easily integrated into existing systems, and more.

The day before this piece went to press, Wired published a piece titled, The Therapy Part of Psychedelic Therapy Is a Mess, which explained that many of the conventional elements of the therapy that is administered alongside psychedelics are not evidence-based. The article draws on a recent Viewpoint published in JAMA Psychiatry on the topic of harms in PATs more broadly.

Dutch Government Forms MDMA Commission; NIH Forms Psychedelics Interest Group

The Netherlands’ Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport, Ernst Kuipers, received a sixty-page report (here’s a machine translated English version of the report) on the therapeutic applications of psychedelics in early March.

In late March, OPEN Foundation reported that the Dutch government has established a State Commission to study the impact of MDMA on individuals, society and public health; including potential medical applications.

Earlier this year, the U.S. National Institutes of Health hosted the first meeting of the Psychedelic Science and Medicine Interest Group. The group will host monthly virtual meetings and aims to “foster the dissemination of knowledge through invitation of guest speakers and journal clubs”.

UC Berkeley’s The Microdose newsletter interviewed two NIH researchers on the topic.

- MAPS PBC announces positive topline results from long-term observational follow-up study of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD – Press Release

- ICYMI: Legendary psychedelics researcher and author Rick Strassman’s The Psychedelic Handbook is available now.

- European ‘shamans’ took psychedelic drugs 3,000 years ago – National Geographic, and the underlying paper is here: Guerra-Doce et al., 2023.

- Oregon Health Authority has issued the first two licences of its Psilocybin Services program, both for manufacturers. Over on the Harris Bricken Sliwoski LLP Psychedelics Law Blog, Vince Sliwoski asks “Now What?”

- Clairvoyant Therapeutics Announces First Patient Dosed in Europe in Phase 2b Clinical Trial Exploring Psilocybin Therapy as a Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder – Press Release

- Some Colorado communities don’t want psychedelic healing centers — but can they stop them? – The Denver Post

March 2023 Psychedelic Research Bulletin

March reflected the blossoming of psychedelic research with 23 new articles covered. In this recap, we reflect on the new microdosing study, detailed brain measures under the influence of psychedelics, a null result with psilocybin for depression, and meditation x psychedelics.

Weekly Bulletins

Join our newsletter to have our Weekly Bulletin delivered to your inbox every Friday evening. We summarise the week’s most important developments and share our Weekend Reading suggestions.

- The same dose employed in Ross et al, 2016.

- Study therapists and other study staff were not asked to guess whether placebo or psilocybin had been administered.

- The antidepressant response from the placebo session thus limited the magnitude of improvement that is possible with psilocybin and the possibility of a significant difference between the two.