Welcome to the third issue of The Psychedelic Practitioner, a publication for the evolving practice of psychedelic care.

Today, we turn to the crescendo of the psychedelic journey: the Dosing, or Ceremony. This theme anchors our key interviews and insights, including Dr. Sara Tai’s reflections on her work as a psychedelic therapist, guidance from our practitioner network on navigating challenging experiences in the dosing room, and—as always–perspectives from our Ethics Corner authors. We also share broader updates from across the field.

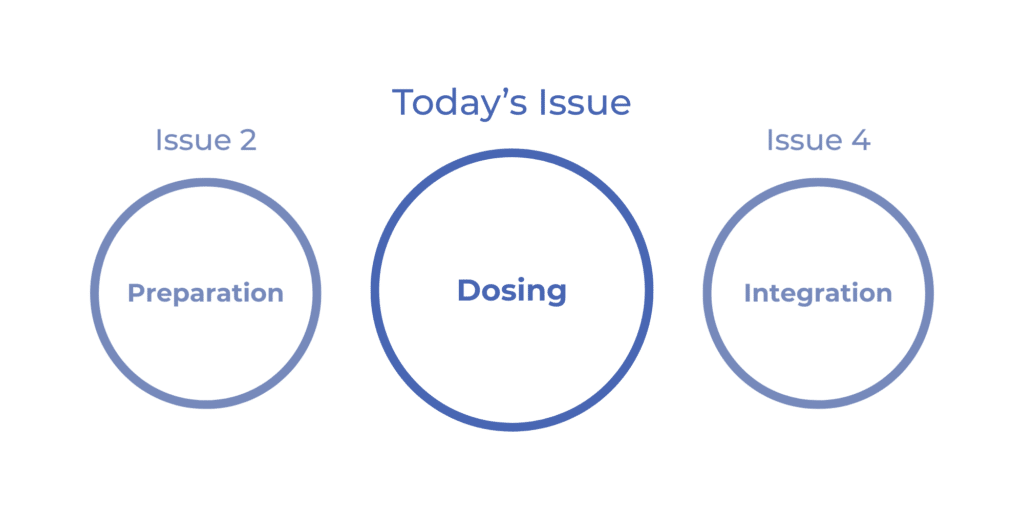

This is the second instalment in a three-part series, with the next Issue, focusing on Integration.

As a reminder, Issues are currently published every other month. Join our free newsletter to receive them:

Your feedback continues to shape these conversations, and our inboxes are always open.

Josh Hardman and Alice Lineham

The Editors, The Psychedelic Practitioner

Sponsor Message

Psychedelic Alpha is grateful to the folks at Fluence, sponsors of The Psychedelic Practitioner.

Build a strong foundation in psychedelic therapy with Fluence’s Essentials of Psychedelic Therapy course.

This 6-week, CE-granting course is the cornerstone of Fluence’s professional training pathway, offering a rigorous introduction to psychedelic therapy, preparation, and integration. Enroll by February 19th and join more than 8,000 therapists who have expanded their clinical skillset through Fluence training.

Vitals

Vitals is your pulse check on the psychedelic field: a concise scan of the developments, discoveries, and debates that matter most for practitioners. Each item ends with the Bottom Line, for those of you who are pushed for time or want our read on the news.

Psychedelic Americana: Surveys Provide Look at What Americans See, Think, and Do with Psychedelics

The release of two large-scale surveys offer new insight into how Americans think about and use psychedelics.

The first, conducted by Psychedelic Alpha and Ipsos, revealed that psychedelics-related media exposure remains relatively low in the general population, with 70% of respondents reporting seeing no coverage on the topic within the past 90 days.

Attitudes towards psychedelics, for both personal use and mental health care, remain somewhat divided. Older adults held more negative views and felt less comfortable with use across various settings—from clinical contexts to social environments with friends or family. Men and those with higher educational attainment were more comfortable with the prospect of taking psychedelics across all settings, the latter possibly signalling links between education, trust in healthcare, and familiarity with the research. Black and Hispanic respondents were more likely to express negative views or concern.

A dominant concern expressed by respondents was the risk of negative psychological experiences, demonstrating that ‘bad trip’ narratives still loom large amongst public perceptions. That said, 21% of respondents reported that their views on psychedelics had become more positive over time.

The second survey, conducted by RAND with a nationally representative sample of 10,122 American adults, focused on actual use patterns. The think tank’s findings showed that roughly 10 million U.S. adults microdosed psilocybin, LSD, or MDMA in 2025, with nearly 70% of psilocybin users microdosing at least once—a noteworthy figure considering the underwhelming evidence for sub-perceptual dosing (covered in our last Issue).

Psilocybin, both mushroom and synthetic forms, were the most commonly used psychedelic overall (11 million users)—more than double that of MDMA (4.7 million). Perhaps most surprising was the prevalence of Amanita muscaria mushroom use (3.5. million), which surpassed both ketamine (3.3. million), and LSD (3 million), according to the survey. Amanita’s legal status in the U.S., along with its frequent—and often mislabeled—appearance in mushroom chocolates, likely contributes to elevated figures despite its toxicity. This hints at broader issues within the U.S. edibles market in which a lack of regulatory oversight is increasing risks of unintentional overconsumption and adverse reactions amongst users.

Bottom Line: Public exposure to psychedelics-related media remains limited, with perceptions varying widely across demographic groups. Microdosing appears to have a firm foothold among Americans, despite null findings in trials. Public perceptions will inevitably shape the therapeutic landscape, and demographic divergences may deepen existing inequities in who seeks and receives treatment in the years ahead.

At the FDA: Psychedelics Now “a Third” of Workload

Psilocybin drug developer Compass Pathways hosted a virtual event last month to discuss its launch plans for its synthetic psilocybin candidate (COMP360) in treatment-resistant depression, as well as late-stage development plans for PTSD.

On the latter front, it revealed a ‘finalised’ Phase 2b/3 trial design that will see 234 PTSD patients receive two doses administered in a 12-week blinded portion (on Day 1 and in Week 4), as well as an open-label dose for those who do not respond in the blinded portion, or who subsequently deteriorate. The company’s Chief R&D Officer Michael Gold told attendees that the company’s belief is that, “based on prior studies with COMP360, is that more than one dose of a classical psychedelic is likely to be the best approach to maximise benefit”.

Compass also shared that FDA has cleared an investigational new drug (IND) application for the program, and that it hopes to begin screening patients this quarter.

Elsewhere, 5-MeO-DMT drug developer GH Research saw a hold on its U.S. IND finally lifted after more than two years in limbo. The company, which is developing an inhaled formulation of the drug for treatment-resistant depression, hopes to commence a global Phase 3 program this year.

Bottom Line: It looks set to be a very busy year for the FDA when it comes to psychedelics. Indeed, Division of Psychiatry Director Tiffany Farchione said at a recent event that reviewing psychedelics-related matters is “fully a third of my workload at this point.” For more on the U.S. landscape, see Going Global.

Virtual Practice: Can AI Prepare Practitioners?

Many are hopeful that 2026 could mark the arrival of the first FDA-approved psychedelic treatment. But alongside this excitement is increasing attention on just how training and credentialing will work, and whether there will be a sufficient cohort of skilled, ethical, and attuned practitioners to deliver psychedelics in the case of an approval. With the timeline to potential approvals now measured in months, how will the workforce be adequately prepared to administer these therapies?

One part of the puzzle, some organisations believe, may lie in artificial intelligence (AI), and have begun developing and offering AI-powered training platforms designed to prepare practitioners to deliver psychedelic sessions from day one.

First on the scene was Fireside Project, which announced the launch of ‘Lucy’ in December 2025. Leveraging over 7,000 anonymised conversations from the non-profit’s psychedelic support line, Lucy provides an interactive, voice-based simulation platform for practitioners to practice delivering therapy. The organisation hopes that its chatbot will expose practitioners to situations that closely mirror real-world challenges, helping them develop the interpersonal skills required during psychedelic sessions, and receive personalised, trackable feedback.

More recently, Sabba Collective introduced ‘Sabba Praxis’, another AI-based simulation offering that aims to provide a space in which practitioners can work through challenging scenarios—defusing paranoia, managing anxiety, supporting ego dissolution—across a range of personas. Like Lucy, the platform provides feedback on session-specific variables to support skill progression.

Fireside currently offers initial modules free to researchers, academic teams, or drug developers through an early access program, though it’s currently unclear how this will evolve. Sabba Praxis, on the other hand, charges $20 for 20 simulations, with a deeper training tier, comprising videos and vignettes of Bill Richards and Mary Cosimano role-playing therapeutic encounters, for $299.99.

Bottom Line: As psychedelic approvals draw nearer, so too do concerns about whether the workforce will be ready. Artificial intelligence is increasingly being deployed in an effort to address this potential training lag, but questions remain about the role these tools should play, what data they ingest, how they are priced, and the appropriate role that virtual simulations can play in preparing someone for the realities of sitting in the room with a patient.

Taking Stock: Reflections on Psychedelics in 2025

Psychedelic Alpha’s 2025 Year in Review is wrapping up as 2026 gets underway in earnest. In case you missed it, the series featured four guest articles, each of which focused on different aspects of ‘real-world’ psychedelics use.

The first saw Healing Advocacy Fund’s Taylor West provide a review of the lessons we can learn from state psychedelics programs and what the future may hold (Op-Ed: Psychedelics in Practice: What the State Programs Are Teaching Us). Next, The Psychedelic Consultancy’s Monica Schweickle teamed up with our Editor, Josh Hardman, to pen a piece on the progress of Australia’s psychedelics system thus far and what we’re keeping an eye on in 2026 (Australia’s Psychedelic Experiment: Progress, Pitfalls, and What Comes Next).

Later in January, researcher and psychotherapist Helena Aicher reflected on how Europe’s psychedelics landscape evolved in 2025, noting that psychedelic-assisted therapy “is now developing under intense public, political, and commercial attention”, which she distinguishes from the conditions under which Europe’s first real-world model, Switzerland’s, emerged (Op-Ed: Beyond Clinical Trials: Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy in Europe’s Real World).

Finally, a group of authors from the Center for Psychedelic Public Health argued that public health has been largely missing from the psychedelics landscape. In doing so, they put forward a sort of manifesto or agenda for psychedelic public health (Op-Ed: From Psychedelic Prohibition to Psychedelic Public Health).

Elsewhere in the 2025 Year in Review series, we published three video reviews of the year gone by, presented by our Editor Josh Hardman, reflected on ten standout stories from 2025, shared views from across the field on what to expect in 2026, and more.

Bottom Line: As what is expected to be an incredibly busy year gets underway, take a moment to reflect on 2025 and consider some of the broader issues that shape our field.

Introduction: 'Dosing' or 'Ceremony'

Dosing, or ceremony, is often described as the crescendo of the psychedelic journey—the centre of a much wider arc, held together by the scaffolding of preparation and integration. As we explored in our last Issue, preparation shapes how someone arrives to the dosing session—psychologically, emotionally, and intentionally. Integration, in turn, determines how effectively the individual makes meaning of, and carries forward, the content and insights gleaned during dosing.

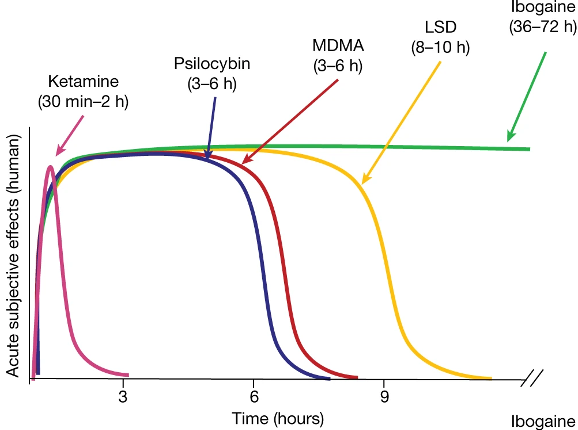

It is difficult to define a “typical” psychedelic dosing session, or even a typical dose. Experiences vary markedly across compounds, with some psychedelics inducing rapid, intense states and others unfolding more gradually. What constitutes a “dose” also differs dramatically across paradigms: per protocol within a clinical trial, determined by practitioner judgement in traditional settings, or shaped by ritual norms established over generations. Even within Western settings, the same numerical dose can produce vastly different responses depending on sensitivity, mindset, sex, genetics, trauma history, intentions, concurrent medications, or even the gut microbiome. There are even anecdotal accounts of individuals in Ayahuasca ceremonies consuming very little, or nothing at all, and still entering full psychedelic states.

In many traditional healing contexts, people speak instead of ‘ceremony’. Ceremonies, often held in large groups, are embedded in wider cosmologies and oriented toward systemic, communal, or ecological harmony, extending far beyond individual symptom relief. In many lineages, the healer or shaman ingests the psychedelic substance alongside, or even instead of, the participants. Their role is to protect and navigate the energetic or spiritual landscape of the ceremony—utilising lineage-specific tools such as song, smoke, or plant spirits—acting as an intermediary between participants and the wider cosmological frame in which the work is held.

Western clinical trial environments, by contrast, place far less emphasis on cosmology and far more on individual psychological processes. Dosing sessions typically operate within a 1:1 or 1:2 patient:facilitator structure. While many protocols encourage a largely inward, non-directive approach, others incorporate active therapeutic engagement. Across models, the aim is to support psychological exploration and the activation of one’s own healing capacities. The role of the therapist or monitor varies considerably across protocols, spanning minimal ‘psychological support’, through to structured psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy—although plenty of debate surrounds the precise distinction, and perceived separability, of these roles (read our interview with Prof. Sara Tai for more).

Across paradigms, psychedelics evoke a plethora of experiences. Among the most remarked upon are visionary states: enhanced visual acuity, intricate geometric patterns, and encounters with non-human entities or deities—phenomena that may be associated with therapeutic benefit. Certain motifs recur with striking consistency across contexts. Ayahuasca is frequently linked with serpentine or cosmic-type imagery; DMT with hyper-dimensional realms populated by “machine elves”; and a particular mushroom variety with sightings of miniature people.

Such experiences are not new. Indigenous groups around the world have long described such visions, often placing them at the centre of their cosmologies. Their emergence in clinical settings, however, has sparked debate about whether such possibilities should be discussed during participant preparation. Some say that naming them risks priming; others maintain that transparency is essential. Contemporary neuroimaging frames these visions as hallucinatory phenomena arising from 5-HT2A receptor agonism and network disintegration, whereas traditional communities may understand them as genuine interactions with spirits, energies, or ancestral realms.

Visionary phenomena are only one dimension of psychedelic dosing. Emotional material often takes centre stage: fear, joy, grief, love, shame, and long-buried memories can all surface and undulate— sometimes with pace, in other times with slowness. Formative experiences may be relived, and deeply hidden parts of ourselves may emerge. The support required varies widely: for some, the release is cathartic, while for others it may feel overwhelming without sufficient support.

Somatic experiences also frequently arise: trembling, nausea, temperature fluctuations, and feelings of floating or dissolving, for example. In Ayahuasca communities, such sensations may be seen as energetic release, with purging viewed as the ultimate act of cleansing torments or burdensome energies. Later in this Issue, Professor Sara Tai offers reflections on this from a Western perspective.

Regardless of context or paradigm, safety remains the backbone of any dosing session or ceremony. A lot of this harks back to preparation, the setting of boundaries, comprehensive screening, and psychoeducation—but also perennial questions of set and setting: Who is in the room? What is in the room? What training, or experience, should a facilitator have to steward these states? What environment best supports the unfolding of these experiences? And what skills must a therapist or mentor draw upon to navigate, or simply hold, a challenging experience? We will be exploring some of these questions throughout this Issue.

In Practice: Prof. Sara Tai on Psychedelic Dosing

Sara Tai is Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Manchester and a leading figure shaping contemporary therapeutic frameworks for psychedelic-assisted therapy. She is a practising consultant clinical psychologist working with people who experience chronic mental health issues. Her work spans the development of psychological interventions and psychedelic-therapy manuals, training of psychedelic therapists worldwide, and leading and collaborating on large-scale psychedelic clinical trials.

Tai describes her approach as principles-based and grounded in a biopsychosocial understanding of distress, drawing in particular on Perceptual Control Theory. Central to her work, she says, is the view that psychological distress arises when individuals lose a sense of control over experiences that matter deeply to them. Across therapeutic contexts, including psychedelic-assisted therapy, her focus is on helping individuals regain control by working within their own frame of reference rather than imposing meaning or direction from outside.

The perspectives shared here arise primarily from Tai’s clinical and research work with individuals experiencing significant mental health difficulties. She acknowledges that psychedelics are engaged with for many different reasons across settings, but her emphasis remains on safety, therapeutic responsibility, and principled clinical practice.

Prof. Sara Tai, Professor of Clinical Psychology and psychedelic therapy researcher

The Role of the Practitioner in Psychedelic Dosing Sessions

The Psychedelic Practitioner: What do you think is the core role of the practitioner during a dosing session, and which competencies do you think matter the most in real time?

Prof. Sara Tai: The dosing session is about creating the conditions for attention to move towards what matters most to the individual and sustain attention there long enough to process the emotions that arise. With good preparation, the hope is that the person’s experience naturally brings them into contact with material that is emotionally relevant and meaningful. The practitioner’s role is to help them feel sufficiently safe to stay with that experience—to remain open, curious, and engaged long enough for something new to emerge.

That requires a therapist who can remain calm and grounded, particularly when difficult material arises. If a practitioner becomes anxious at the first sign of struggle and feels compelled to intervene, there is a real risk of disrupting the person’s processing. The ability to tolerate uncertainty and emotional intensity—both in the participant and in oneself—is essential.

With good preparation, the hope is that the person’s experience naturally brings them into contact with material that is emotionally relevant and meaningful. The practitioner’s role is to help them feel sufficiently safe to stay with that experience—to remain open, curious, and engaged long enough for something new to emerge.

Curiosity is also central. We invite participants to approach their experience with curiosity, but the practitioner must do the same. The work involves careful observation and patience: ensuring the experience is not so easy that it bypasses meaningful engagement, but not so overwhelming that the person loses the capacity to stay with it. This balance cannot be reduced to a set of rules; it is guided by principles that are applied moment by moment. We are aiming for the person to be able to allow themselves to be exposed to experiences that naturally arise but be able to process them in ways they might not have encountered before.

TPP: What principles guide you when navigating a challenging experience or sitting with uncertainty in a dosing session?

Tai: We can never fully know what another person is experiencing. I don’t work from a traditional model of empathy that assumes we can put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. Instead, my approach is grounded in what the person communicates, including what they have already shared with me during preparation—their history, their patterns of coping, and how they tend to respond when emotions become intense.

I don’t work from a traditional model of empathy that assumes we can put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. Instead, my approach is grounded in what the person communicates, including what they have already shared with me during preparation.

Those principles remain constant, but how they are enacted varies depending on the individual. If someone has described difficulty tolerating strong affect or a tendency to panic, I will apply the same principles differently than I would with someone who is more tolerant of intense emotions. The aim is always to maintain safety and connection, ensuring the person knows they are not alone while allowing them to remain immersed in their experience.

Interventions, when they occur, are subtle and guided by the individual. My presence as a therapist can be communicated in many ways—through proximity, posture, or tone—without immediately resorting to physical contact. If physical contact is used, it is something that I will have discussed and practised in preparation, and it unfolds responsively, guided by how the person engages. For example, if I think somebody looks distressed, I might put my hand close to theirs, so they are aware of my presence even though I’m not physically touching them. With my hand so close, they can feel the heat of it and have a sense that I’m there. If they respond by taking my hand, then I know they need that extra support, but my actions are being directed by the person.

Everything a practitioner does has an impact. In that sense, we can never be entirely non-directive. The critical issue is whether our actions are led by the participant’s needs and signals, or by our own anxiety and assumptions about what is helpful. Whether something is ‘helpful’ can only be determined from the perspective of the individual being helped.

Everything a practitioner does has an impact. In that sense, we can never be entirely non-directive. The critical issue is whether our actions are led by the participant’s needs and signals, or by our own anxiety and assumptions about what is helpful.

Psychedelic Dosing Frameworks

Editor’s Note: Within contemporary psychedelic practice, many approaches are utilising a “psychological support” model, focused on non-directive, minimal intervention where therapists or ‘monitors’ aim to provide safety and supportive presence rather than directing, interpreting, and shaping the person’s process.

Although the terms are often used interchangeably, psychological support differs from psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, which is more of a principle-guided therapeutic intervention involving active monitoring, relational attunement, and therapeutic framing before, during and after.

TPP: Many contemporary approaches are heading towards a minimal non-directive ‘psychological support’ model. From your experience, how does this approach play out during a dosing session?

Tai: It depends very much on who you are working with. Most of my work is with people experiencing significant problems affecting their mental health. For these individuals, experiences can escalate rapidly—from unfamiliar sensations to fear, paranoia, or emotional overwhelm. In such cases, I am very clearly practising psychedelic-assisted therapy rather than minimal psychological support. That doesn’t mean constant intervention. With some participants, very little is required. But if I notice indicators that someone is no longer able to stay with their experience—changes in facial expression, opening their eyes, removing headphones—then I respond. That response is not about directing the experience, but about re-establishing safety and connection, guided by what the person has consented to and what we have prepared for together.

For individuals without a history of significant mental health issues—perhaps those seeking a spiritual journey—a largely hands-off psychological support model may be sufficient. However, assumptions should never be made lightly. Regardless of mental health history, people never know what might arise during dosing. I’m always mindful of what I learned about that person through preparation, what they have said they might need, and what they’ve consented to.

If I notice indicators that someone is no longer able to stay with their experience—changes in facial expression, opening their eyes, removing headphones—then I respond. That response is not about directing the experience, but about re-establishing safety and connection

TPP: As psychedelic dosing frameworks become more standardised, how can they remain flexible enough to accommodate individual differences—such as neurodivergence, trauma histories, or cultural backgrounds?

Tai: My concern with standardisation is that manuals can easily become rule-based: when this happens, do X; when that happens, do Y. That approach is fundamentally at odds with the realities of psychedelic states.

I work with principles, not rules. If the principle is safety, and I observe something in-session that suggests safety may be compromised, I respond. How I respond depends on how the person reacts, and my next step is informed by that response. This is what flexibility looks like in practice—it is always led by the individual. This is particularly so when it comes to neurodivergence, trauma histories, or cultural backgrounds, we have to prioritise that individual’s specific and idiosyncratic needs.

In contrast, rigid manualised approaches encourage stock responses, particularly among less experienced facilitators. This increases the risk of making assumptions about a person’s needs and getting it wrong. No two people with the same trauma history, for example, will have the same experience or needs. In altered states of consciousness, this can be actively unhelpful. Two approaches may look similar on the surface, but they are worlds apart in how they function in the room.

Navigating Somatic Experiences

TPP: In the context of psychedelic dosing, why is the felt, or somatic emotional experience, considered therapeutically relevant?

Tai: We rarely respond to experiences in a single, unified way. At any moment, multiple needs and goals are operating simultaneously, and they are not always compatible. For example, someone reliving a grief experience may feel a strong pull to stay with it, alongside an equally strong urge to escape. Those competing needs generate intense and often confusing somatic responses.

From my perspective, psychedelic experiences allow people to become aware of these emotional incompatibilities and, over time, to find new ways of balancing the needs underlying them that feel acceptable and meaningful. During dosing, the focus is not on making sense of these sensations in the moment. My role is to provide a safe environment in which all of these sensations can arise without the person feeling compelled to immediately interpret or resolve them. Dosing is all about developing awareness.

Meaning-making happens later, during integration. When participants revisit the experience, it is often not the sensation itself that matters, but the meaning they now attribute to it and how it connects to their current life.

From my perspective, psychedelic experiences allow people to become aware of these emotional incompatibilities and, over time, to find new ways of balancing the needs underlying them that feel acceptable and meaningful

Advice to Practitioners

TPP: Dosing days can be emotionally demanding and unpredictable for both participants and practitioners. From your perspective, what are the key challenges practitioners typically face during these sessions, and how can they maintain their own wellbeing and boundaries throughout the process?

Tai: The primary challenge is sustaining attention. Your sole focus needs to be the person in the room. Fatigue, travel, and competing demands can all interfere with that, increasing the risk that decisions are influenced by the practitioner’s own needs rather than the participant’s.

Awareness is crucial. We are human and there might be times when our own issues or needs might be pulling at our attention. There may be times when the most ethical decision is to step back and ask for support from a colleague. That requires honesty and integrity, but it is always in the service of the person you are working with.

Awareness is crucial. We are human and there might be times when our own issues or needs might be pulling at our attention. There may be times when the most ethical decision is to step back and ask for support from a colleague.

TPP: Is there any additional guidance you would offer to a practitioner going into their first dosing session?

Tai: Acknowledge your apprehension. It is normal to feel anxious, or whatever other emotions might emerge, and that does not make you unprofessional. We cannot always be emotionally neutral. What matters is awareness—knowing what is yours and what belongs to the person you are working with. As much as we try to be as non-directive as possible, we cannot be completely so. Awareness, therefore, is crucial so you can be sure that everything you do is truly what is best for the person you are working with.

Seek supervision, take breaks, and be honest with yourself. You will not always get it right. Sometimes you may intervene too quickly; at other times, you may wait too long. Learning comes from reflection and from feedback—asking people, during integration or later, how your presence affected them.

This work requires humility. Expertise grows not from perfection, but from careful attention, honesty, and a willingness to keep learning.

Seek supervision, take breaks, and be honest with yourself. You will not always get it right…This work requires humility. Expertise grows not from perfection, but from careful attention, honesty, and a willingness to keep learning.

Views from the Field: The Dosing Session

You’ve prepared over the course of weeks or months, and your client may have been waiting for what feels like an eternity: dosing day is finally here. How is the therapist to balance the demands of keeping clients safe, managing expectations, and maintaining hope for the most positive outcome? While dosing day may be the most highly anticipated moment in the psychedelic therapy process, it can also bring a number of challenges and carry immense uncertainty. This can distract therapists with anticipatory anxiety and worry.

While there truly are many details to attend to—room preparation, supply lists, sound checks, screening questions, transportation arrangements, and more—the key principles guiding dosing day are generally very simple. Client safety should be the organizing principle behind everything. Learning how each of the details relates to safety can make them feel more logical and easier to follow. Therapists’ behavior and actions are also guided by this principle, with the understanding that a balanced, attentive, and professional demeanor is part of what supports a successful dosing day.

Another key principle of a dosing session is managing expectations, including your own. You may be hopeful for a particular client’s outcome or dread their disappointment if profound change is not immediately apparent by the end of the day. We ask clients to remain open-minded about their psychedelic experiences; it is essential that therapists cultivate and model open-mindedness as well. During dosing days and throughout the integration phases of treatment, curiosity and a willingness to explore what is actually happening serve as antidotes to premature conclusions and open the door to long-term change.

As the field evolves and more therapists have opportunities to guide clients through dosing sessions, the possibilities for learning are expanding exponentially. With client privacy and confidentiality always in mind, finding appropriate opportunities to debrief with clinical team members, colleagues, trainers, or consultants supports continued reflection on dosing sessions and the work that surrounds them. There is also a wealth of resources created by people who have undergone psychedelic therapy to enrich these conversations, often in the form of essays and books, podcasts, and recorded conference talks. At Fluence, we offer a growing number of CE courses that include video and discussion of real psychedelic therapy sessions.

Learning should always be an ongoing endeavor that includes time for listening, reflecting, and integrating. Your experiences and insights as a therapist are a vital contribution to the growth and enrichment of the field.

Elizabeth Nielson, PhD, Fluence Co-Founder and CEO

Practitioner Voices

For this Issue, we were interested in exploring some of the unique challenges that can arise in psychedelic dosing sessions and ceremonial contexts, along with the practical ways these challenges can be anticipated, navigated, and supported before, during, and after the experience. We asked three active practitioners to share their insights, reflections, and guidance with our readers.

Emily Fishel, U.S. based psychotherapist with a specialism in psychedelic-assisted therapy

Emily Fishel is a U.S.-based psychotherapist who completed her clinical training at Columbia University, where she specialised in psychedelic-assisted therapy as part of the world’s first in-degree program of its kind. Fishel also serves as a study therapist on several psychedelic clinical trials, including Compass Pathways’ Phase 3 trial investigating psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression.

TPP: How do you manage participant disappointment?

Emily Fishel: Participating in a psychedelic clinical trial requires significant sacrifice and an enormous time commitment. Many patients are willing to do this because they’ve read about how life-changing psychedelics can be, and their expectations are understandably sky-high. To manage expectations, I work to ensure that by the dosing day, participants understand that every psychedelic experience is unique. Although intentions matter, I emphasize that the most helpful approach is trusting that something meaningful can emerge from whatever comes up.

In cases of placebo or low-dose experiences, I invite participants to explore what they might still gain from spending a day without their phone or outside distractions in a quiet, supportive space. I emphasize that principles like “trust, let go, be open” are just as helpful when navigating disappointment or difficult emotions during a low-dose experience as they are during a more intense psychedelic one.

TPP: How do you ensure self-care before, during, and after dosing sessions?

Fishel: For me, leaning on the team involved in a dosing day is essential; it’s simply too long and too demanding a job to do without support. Before each session, I take a moment to remember what a privilege it is to do this work. Witnessing the courage and effort participants bring into the dosing room as they work toward healing consistently grounds me in my “why.” Dosing day is an opportunity for me to practice staying present, not only with the participants’ experience, but with myself as both a clinician and a human. I’m constantly invited to notice my own reactions and impulses and to gently bring myself back to the caring, containing energy I aim to embody.

And of course, comfy clothes and a healthy lunch are essential.

TPP: What is one thing you do differently in the dosing room now, as compared to when you first started?

Fishel: I used to be very focused on creating a distraction-free “bubble” for participants on dosing day. Over time, I’ve come to see external disruptions as an inevitable and meaningful part of the experience rather than something to eliminate. I work in NYC, and it’s not uncommon for a session to be disrupted by drilling, sirens, or hammering outside. Of course, we use noise-canceling headphones and music, but some level of interruption is unavoidable. When participants are adequately prepared, these moments are opportunities to practice noticing distraction, tolerating discomfort, and gently returning to their internal experience.

Rebecca Lerendu Mbonga, Europe-based psychedelic-assisted therapy practitioner

Rebecca Lerendu Mbonga is a Europe-based sound healer, NeuroDynamic Breathwork facilitator, and psychedelic-assisted therapy practitioner. Her work spans international retreat settings, including women’s retreats in Portugal and retreats in Peru and New Zealand, where she supports participants through breathwork, sound, and psychedelic preparation, dosing, and integration.

TPP: How do you manage intense emotional release during a dosing session or ceremony?

Rebecca Lerendu Mbonga: A lot of the work happens before the ceremony begins. During the preparation talk, I take time to explain the different ways emotional release might show up—crying, shaking, screaming, anger, or even the urge to leave. When people know this is possible, they’re less likely to feel afraid or think something is wrong. I also gently frame these moments as meaningful releases, often a way for the body and nervous system to let go of what no longer needs to be carried.

We make clear agreements ahead of time, including the intention to stay within the ceremonial space even if things feel uncomfortable. This helps create a sense of safety and trust in the process. During intense moments, I focus on steady presence, soft verbal reassurance, simple breath guidance, and reminding the person that they are safe, supported, and not alone.

TPP: What is the most important lesson you have learned from a challenging dosing session or ceremony?

Lerendu Mbonga: Some of the most challenging journeys have also been the most meaningful for me. Difficult experiences can bring old pain or fear back into awareness, but when this happens in a safe and supportive environment, it allows those experiences to be met differently than before.

The lesson I’ve learned is that challenging moments are not random or unnecessary. The medicine seems to bring forward what is ready to be seen, felt, or understood. When I resist less and allow myself to trust the process, even uncomfortable experiences become more workable. Over time, I’ve learned that these moments often carry deep insight and healing, sometimes revealing their meaning slowly, well after the ceremony has ended.

Dr. Helena Aicher, psychotherapist and postdoctoral researcher

Dr. Helena Aicher is a psychotherapist and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Zurich. Her PhD explored the effects of ayahuasca and related compounds on self‑ and other‑related processes, psychotherapy‑relevant mechanisms, and contextual factors. Dr. Aicher is currently involved in several clinical and retreat‑based trials investigating DMT/harmine and 5‑MeO‑DMT formulations in group settings.

TPP: How do you manage prolonged periods of silence, inactivity and introspection during dosing sessions?

Dr. Helena Aicher: “There’s nothing to do, reach, or achieve” – this is something we sometimes tell our patients. And I guess this is advice for us therapists as well. I orient to silence as an essential element of the work. It’s about presence, at the core of the therapeutic stance. One might feel the pull to “do something” during long quiet stretches, but I guess we can trust the intelligence of stillness.

We can be with our breath, posture, and a soft, receptive attention, so our presence remains steady and perceptible even without words or visible “action.” I might track subtle shifts in the participant’s breathing and muscle tone, and I’m also checking in with myself – the resonance, or embodied countertransference. When needed, I offer minimal anchors: a gentle check-in, an invitation to notice bodily sensations, or a few words.

Sometimes bodily immobility can also indicate a dissociated state (as compared to a deeper meditative state, for example). We can never know this from the outside, but we might have an intuition (a felt sense based on experience). In such a situation, I might gently initiate contact with the patient.

TPP: How do you navigate a dosing session in which the trust, or the alliance, is compromised?

Aicher: When trust fractures, the priority for me is to stay calm and present. We can slow down, reduce stimulation, shift the bodily position, and re-establish choice: reminding the participant they can pause, redirect, etc. Sometimes clarification happens in the moment; other times it becomes material for integration. Safeguarding dignity and agency can be more therapeutic than pushing forward or confronting. If someone wants to leave the space for example, I’d remind them of our agreement to “start together and end together”. Of course, preparation matters here, i.e. conversations around consent, agreements, safety, autonomy. Mostly I work with groups, and then there’s always a co-therapist present. This can help, because the interpersonal dynamics might develop differently and we can offer complementary presence.

In the integration phase, I acknowledge the rupture without defensiveness. Naming what seems to be happening (“something feels off between us”) can invite exploration of the difficult situation. Along the way we might understand different layers of that experience, probably something in the immediate situation, probably a reactualization of an interpersonally difficult dynamic (with a childhood caregiver or so), etc. I wouldn’t take it personally, but also not do as if I had nothing to do with it. As therapists, we’re usually part of the process, with who we are, and also as objects of projection and transference. Psychedelics can intensify these interpersonal dynamics.

TPP: What is one thing you do differently in the dosing room now, as compared to when you first began?

Aicher: Maybe it’s less active intervention, more listening – to the participant, to my inner world, to the relational field. Maybe I’ve become more comfortable with “whatever happens” – chaos, difficult feelings, despair, or anxiety – without feeling the need to “do something about it,” but rather to “hold” it, offer containment, be there. Probably I’ve become more relaxed with just being present, and more tolerant of ambiguity.

Maybe I’m less focused on trying to “do it correctly,” less afraid of doing something “wrong” – less doing, more being – with the understanding that ruptures and frictions are often very valuable material for later integration. Probably I’m also more attentive to pacing across the full arc of the therapy, allowing experiences to remain “unfinished,” and trusting that meaning will emerge through integration, relationships, and time.

I think that by working therapeutically with psychedelics on a regular basis, the experience also becomes, in a way, more normalized. I think I’m more relaxed in the sense that we can also experience joy, lightness, and humour together. Therapy, also psychedelic therapy, is not only serious. Sometimes we experience cosmic jokes, and we experience simply being humans together — with the suffering, confusion, fragility, and longing, but also the beauty, the wonder, and simplicity.

Not that these insights are “new,” but over the years they probably became a bit more embodied or natural.

Going Global

Going Global is your round-up of developments from around the world, from policy reform and insurance coverage decisions to shifting cultural attitudes and global access initiatives.

Today’s Going Global leans heavily towards the U.S., but for other developments, take a separate look at a recent Psychedelic Alpha Op-Ed on how Europe’s psychedelic landscape evolved in 2025.

Washington Watch: Psychedelics Still Face Political Hesitancy

In December, shortly after Issue 2 published, President Trump issued a directive that marijuana be moved to Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act. While doing nothing for psychedelics, some advocates viewed the move as evidence of a changing approach to drug scheduling in the administration.

But elsewhere, there are hints that the White House continues to take a hard line on scheduled substances. Last week, STAT reported that Trump administration officials vetoed the issuance of a priority voucher to psilocybin drug developer Compass Pathways. Some view it as evidence that members of the administration are hesitant to appear to be endorsing psychedelic medicine.

States Press Ahead: Research Pilots, Accelerated Timelines, and Big Bets

At the time of writing, there are around eighty psychedelics-related bills being considered across the states and at the federal level in the U.S. Since our last issue, some major developments have occurred at the state level.

Last month, outgoing New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed A3852 into law, establishing a psilocybin research pilot program that will see the drug administered at three hospitals in the state, each receiving $2M. While some have touted the move as creating the latest state-legal psilocybin system in the U.S., in reality the two-year program is focused on research.

In mid-December, New Mexico’s Medical Psilocybin Advisory Board convened its first meeting, where it announced that it would now aim to have the program up-and-running by the end of December 2026, a full year ahead of schedule. That means the program could be launching right around the time that psilocybin drug developers seek, and potentially score, FDA approval.

Elsewhere, the State of Texas has awarded $50M to an ibogaine research consortium led by local institutions. The funding is dependent, however, on a private entity matching it dollar-for-dollar. The research agenda revolves around ibogaine for PTSD, substance use disorders, and traumatic brain injury.

Oregon in Focus: The Latest Look at State Psilocybin Data

We’ve recently updated our Oregon Psilocybin Services Tracker, which provides a look at how the U.S.’ first state-regulated psilocybin system is faring, with data from Q3 2025. The program has now served more than 16,000 clients and generated over $1.7 million in revenue while adverse events across the programme remain low, though Q3 did show an uptick compared with previous quarters.

Session costs continue to place services out of reach for most Americans, with prices ranging from $1,000-$5,000. Some service centres have left the business, reportedly due to high overheads and modest demand.

Q3 also saw a considerable decrease in clients from within Oregon and a marked rise in out-of-state and international customers. How this trend evolves will be interesting to watch, especially as more state-regulated programs come online.

Research Radar

Here, we dive a little deeper into some of the most pressing research topics shaping the world of psychedelic practice. Each item ends with the Bottom Line for those of you who are pushed for time or want our read on the subject.

Which Non-Pharmacological Factors Really Matter?

Psychedelic drugs produce a remarkably vast range of effects, from psychotic-like to mystical-like, even when the same substance is taken at the exact same dose. Both the acute psychedelic experience and longer-term therapeutic outcomes appear to be shaped not only by the pharmacology of the drug, but by a number of factors external to it. Commonly referred to as extra- or non-pharmacological factors, these variables can be separated into those concerned with ‘set’-the individual’s mindset, expectations, and psychological state–and ‘setting’.

Those grouped under the umbrella of ‘setting’ comprise aspects of the physical environment, exposure to sensory inputs, the therapeutic container or modality, and the ritual or cultural framings embedded within the practice.

One element of setting that has received increasing attention is exposure to nature. Sam Gandy and colleagues detail the potential synergistic interaction between psychedelics and contact with the natural world, noting that the combination may amplify a sense of calm, beauty, and interconnectedness with all life. Indeed, many facilitators intentionally design nature-based retreat settings, and although Western clinical psychedelic models typically mandate controlled indoor settings, several major protocols attempt to evoke a sense of nature through plants, nature-based photography, and artwork in dosing rooms.

Beyond the physical environment, music similarly appears to enhance and influence the psychedelic experience. It can guide the emotional tone, imagery, and meaning attributed to unfolding experiences, and is widely regarded as integral for self-exploration during psychedelic therapy. However, while music often promotes calm and safety, interview data also highlight its potential to evoke distress or a sense of being “misguided” when poorly matched. As Steven Gelberg observes, “In psychedelic states, music is no longer music as we ‘know’ it. As if in a dream, it shape-shifts into something vastly more significant, multi-dimensional, an opening to other worlds.” (If interested, consider watching East Forest’s documentary exploring the pairing of music with psychedelics).

Importantly, neither the emphasis on nature nor the centrality of music is novel. Indigenous ceremonial traditions have long been inherently immersed in natural landscapes and have cultivated these relationships for generations. Within these traditions, music similarly serves as a critical component, with icaros functioning as key navigational tools in Amazonian Ayahuasca practices, for example. Understood as channels of healing, communication, and catalysts for extraordinary visual experiences, icaros reflect longstanding ideas about the metaphysical and spiritual properties of music.

Despite the clear importance of these non-pharmacological factors related to setting, we still lack clarity on which of these factors—if any—matter most to the therapeutic process, or how they exert their influence. Conclusive research remains lacking, an issue perpetuated by inconsistent reporting standards across studies (as highlighted in a previous Issue).

The ReSPCT Guidelines have aimed to establish an international consensus on the most important non-pharmacological influences on psychedelic effects. Designed for reporting in psychedelic clinical research, the checklist of items resulted from four rounds of anonymous surveys, yielding 30 extra-pharmacological variables of interest. While the focus was primarily on those falling under ‘setting’, a few exceptions relate more closely to ‘set’, though the cohort of experts was notably divided on the perceived separability of the two concepts.

Music and access to nature consistently solicited high agreement across rounds, whereas items related to cultural competence and safety—defined as the ability to care for patients with diverse backgrounds and address power imbalances in patient-provider interactions—increased markedly across rounds, from 50% to 73% agreement. This pattern may hint at broader trends in Western psychedelic research and practice whereby cultural dimensions gain prominence less through widespread agreement, and more through sustained advocacy which acts to reorient the field’s sense of what matters.

While the guidelines provide a valuable foundation, the demographic composition of the “experts” warrants mention. Despite spanning 17 countries, the panel was overwhelmingly homogenous. Nearly one third of experts had just 1-5 years of experience in the psychedelic field, and more than 80% identified as white; the next largest ethnic group—those identifying as ‘Indigenous’—comprised just 6.5%, with no specification of which Indigenous communities or regions this referred to. Experts from the U.S., UK, and Canada were markedly overrepresented, accounting for 25.8%, 22.6%, and 19.4%, respectively.

The authors acknowledged these limitations, noting that the focus on clinical trials inevitably shaped the panel’s demographics given the concentration of psychedelic research in Western institutions. Even so, the skew raises important questions about what constitutes ‘expertise’, whose voices may be inadvertently excluded in these contexts, and how future complementary endeavours can incorporate non-clinical, community-based, and culturally diverse perspectives when answering these critical questions.

As the field awaits widespread adoption of the ReSPCT guidelines, Robin Carhart-Harris and colleagues at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) began work last year on a new trial examining the interaction effects of psilocybin and the surrounding context (set and setting). Using a 2×2 factorial design, 120 participants will receive either psilocybin or placebo in one of two distinct settings to assess how pre-defined contextual variables influence wellbeing, connectedness, and the quality of the acute experience.

Together, these efforts could deliver progress toward improving the transparency, reproducibility, and validity of this evolving field’s research output, while laying the groundwork for future clinical implementation that is both safe and effective.

Bottom Line: Psychedelic outcomes appear as much determined by mindset and context as by the drug itself. Nature, music, rituals, and cultural context all meaningfully shape individual’s experiences—a reality long recognised in Indigenous traditions and now increasingly acknowledged in clinical research. The ReSPECT guidelines, along with ongoing research at UCSF, aim to systematically understand these influences in clinical settings, promising clearer guidance for delivering psychedelic treatments that are safe, effective, and culturally attuned.

Findings in Brief

📔 Psychedelics > Cannabinoids for OCD: A new scoping review from McMaster University reports no meaningful evidence supporting the use of either synthetic or natural cannabinoids for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The authors cite stronger signals for the use of psilocybin, particularly in cases of treatment-resistant OCD. Speaking to The Guardian, the study’s lead author theorises this divergence may stem from differences in brain mechanisms, with psilocybin holding the advantage due to its apparent ability to reduce connectivity in the default mode network (DMN), an area often hyperactive in OCD. The therapeutic paradigm in which psilocybin is typically embedded (i.e. preparation, integration) may also have contributed to more favourable outcomes, given that we don’t see the same with cannabis.

🐭 Enter Serotonin 1B: The clinical effects of psilocybin are often chalked up to its activation of the serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptor, long associated with the compound’s acute hallucinatory effects. However, recent rodent data suggest that the serotonin 1B (5-HT1B) receptor may also form a piece of psilocybin’s pharmacological puzzle. In line with previous research linking 5-HT1B to antidepressant effects across several drug classes—including traditional antidepressants and ketamine—the study found that this receptor mediates both the acute and persisting behavioural responses to psilocybin in mice. Importantly, given the non-hallucinogenic properties of the 5-HT1B receptor, the findings raise the potential of developing non-hallucinogenic psilocybin-inspired candidates.

🐁 Psilocybin Promotes Growth of Existing Brain Tumours in Mice: A new preprint raises concerns that psilocybin may promote the growth of existing cancerous brain tumours, specifically high grade gliomas, in mice. Given the effect appears chiefly mediated by 5-HT2A receptor activation, it’s unsurprising that LSD and DOI produce similar proliferation. Speaking with our Editor, Dr. Boris Heifets—an author on the preprint—emphasised caution around misinterpretation, stressing that the findings indicate that psilocybin promotes the growth of pre-existing tumours rather than new tumour formation.

🥼 Psychedelics for Binge Eating Disorder: A new Phase 2a open-label study suggests that psilocybin-assisted therapy may hold promise for binge eating disorder (BED). Five adults received a 25mg IV dose of TRP-8803 alongside Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), with all participants reporting reductions in binging episodes throughout the 3-month follow-up period, along with improvements in depression, anxiety, and increased cognitive flexibility.

🇨🇦 Psychedelics for Wellness: TheraPsil has launched what it describes as Canada’s first wellness-focused psilocybin therapy trial. The aim is to “get to people before they develop PTSD, anxiety, or depression”, said TheraPsil CEO Spencer Hawkswell. Eligible participants are expected to pay $4,500 for the three-week programme, with the team hoping that positive results will eventually support provincial healthcare funding.

🩹 Reassessing Psilocybin’s Role in Migraine and Pain: Early signals suggesting psilocybin may be effective in treating migraines have not held up in more rigorous testing. A larger, follow-up RCT with 18 participants compared the effects of receiving zero, one, or two doses of psilocybin. Across all groups, migraine frequency decreased, with no clear separation emerging between psilocybin and placebo conditions. Similarly, a preclinical study examining the analgesic effects of psilocybin, found no measurable effects of the drug across a range of acute and chronic pain models in mice—offering some of the first evidence that psilocybin unlikely acts directly on nociceptive pathways. These findings raise questions surrounding how much of the observed improvements in early studies reflect pharmacological action versus contextual factors associated with healthcare, such as Hawthorne effects.

🍼 Psychedelics for Postpartum Depression: Reunion Neuroscience is gearing up to launch a Phase 3 program of its 4-OH-DiPT prodrug (aka luvesilocin, RE104) in postpartum depression. Following a meeting with FDA, the company says it believes just one positive Phase 3 trial will be needed to secure approval. Elsewhere, the company shared further data from its Phase 2 trial, which also revealed that a higher proportion of participants in the active (30 mg) arm were receiving non-study psychotherapy than the active placebo (1.5 mg) arm at baseline.

💬 Support vs Therapy: Researchers at Johns Hopkins have proposed definitions and criteria for the two forms of interpersonal interaction that remain hotly debated in psychedelic administration: “psychological support” and “psychotherapy”. The framework contends that psychological support is defined by an exclusive focus on safety, whereas psychotherapy is directed towards both safety and efficacy. When attempting to apply these criteria to existing research, the authors state that only four of eleven studies could be cleanly categorised into one mode of the other, and expressed a need for far more precise reporting on interpersonal interaction in future trials.

📋 Is It All in the Prep? In our first Issue, we examined whether the number of therapy hours predicted the therapeutic benefit of psychedelics. The answer, in short, was ‘no’. According to a recent systematic review, however, preparation hours do seem to show a meaningful association with outcomes. Interestingly, this pattern didn’t extend to integration, nor the total amount of hours (listen to the lead author discussing the findings). Harking back to our last edition: it is probably worth investing in preparation!

💊 NMDAR Antagonist for Major Depressive Disorder Succeeds in Phase 2a: Gilgamesh Pharma’s oral NMDA receptor antagonist, dubbed GM-1020 or blixeprodil, succeeded in a Phase 2a study in moderate-to-severe major depressive disorder (MDD).

Ethics Corner: Touch Is Not Just Touch

From informed consent and power hierarchies to therapeutic touch and boundary setting, Ethics Corner explores the nexus where practitioner values, client vulnerability, and evolving norms collide. Expect insights from key opinion leaders, real-world case studies, and candid reflections.

Following on from their inaugural column last Issue, Eddie Jacobs and Bryony Insua return to lead this edition’s discussion.

Is touch permissible? What kinds? In what contexts?

The questions about the ethical boundaries of touch in psychedelic therapies are familiar, and for good reason. As others have noted, “an environment that lacks defined boundaries provides shelter for predatory behaviour as well as increased opportunity for unintentional transgressions.” Many practitioners regard touch as central to the modality, particularly for grounding in moments of intense distress. But wherever the boundaries of permissible touch are drawn, judgment calls remain. It is those moments we want to examine here.

What does wise practice require? One place to begin would be the recognition that even small gestures in the clinic room can carry weight beyond their surface intent. Consider the so-called ’tissue issue’, an example familiar to many therapeutic trainings. When someone hasn’t felt their feelings in years, being in the room when the dam breaks can create a pull to respond. The impulse to hand them the tissues may even feel like basic kindness. Set against the unfolding emotion, the patient’s history, and what each brings into the room, even small gestures can take on layered significance. Does the tissue box say ‘I’m here with you‘? Or does it say ‘that’s enough now‘? What do such judgments invite (or discourage) in the therapeutic process as it unfolds?

What the clinician does with their impulse to act matters: this is true of passing the tissues. It’s true of touch. It’s true in any therapeutic context. But, as they so often do, psychedelics raise the stakes.

Psychedelics loosen the structures that hold meaning in place, opening perception to reorganisation. Patients do not simply feel more – though they might. Heightened sensory responses, vivid internal imagery, intense and often ambivalent emotion – what distinguishes a dosing session from ordinary psychotherapy is both the vividness of internal experience and its near-total obscurity to the therapist: your patient may have become a fat, pot-bellied snake in working through their guilt and shame, or, as their session deepens, be traversing the desert where, unbeknownst to you, they find themselves in identification with the devil. When you reach for a patient’s hand or shoulder, you step out of the role of container for the experience and become part of its content – and you may not be the benevolent anchor you intend.

All relating is, to some degree, shaped by earlier experience. In therapeutic settings, the clinician can be experienced through the residue of potentially harmful relationships – including those that reside within the patient themselves. Under psychedelics, this can be felt more immediately and more bodily. Touch can also land in the midst of imagery that the patient hasn’t yet made sense of: a snapping crocodile, an engulfing spider. As boundaries between inner and outer blur, those present may be abruptly experienced as threatening. Such projections can be dramatic: in one session, the observing clinician was “suddenly and shockingly perceived [by the patient] to be Satan himself.” Your touch can become entangled with whatever was emerging, and – far from offering reassurance – risks giving physical form to fear.

Gabbard’s studies of boundary violations reveal something uncomfortable: therapists who crossed lines experienced themselves as helpers responding to genuine need, not as exploiters. The felt certainty that this patient needs me was often part of the problem. This doesn’t render the impulse to touch suspect per se. It may be an expression of the very care that draws people toward healing vocations. Indeed, sensitivity to such moments is often what makes someone capable of therapeutic work. A clinician who never feels that pull risks being too detached, too defended, or too comfortable with another’s suffering. But an impulse feeling genuine does not place it beyond examination. At moments of great emotional intensity, restraint—the deliberate choice not to touch someone when you feel a pull to do so—may feel cold. Withholding, even, particularly where early neglect is already part of the story. But that pull isn’t the same as clinical indication. Therapeutic restraint – an active clinical skill – may be exactly what allows an internal process to catalyse. We talk about ‘holding space’ for a reason: within the heat and pressure of a dosing session, the therapeutic frame becomes a crucible in which something new can emerge.

Given this uncertainty, what can you do? Holding need not be literal. The voice can anchor, breath can be guided, and necessary grounding techniques employed. Presence, unhurried and non-anxious, can communicate that the intensity of any emerging experience is survivable. These alternatives are not always sufficient, but they are worth reaching for first. Touch carries a weight that other interventions do not, and you cannot see what your touch may interact with – particularly within the vivid, symbolic, sensory landscape of psychedelic experience. Letting the patient’s process take its own shape can be harder than it sounds – perhaps especially when that process is hidden from us and we receive only a few, potentially anxiety-provoking, glimpses into what is emerging. If you could see what you were participating in, you might feel more secure in your judgment. Even then, however, you cannot know quite what your intervention might yield.

We are not issuing a prohibition—you are the one in the room. Whether you are pulled toward touch or restraint, your position and decision-making is worth examining. Supervision, or peer consultation where formal supervision is not available, provides a space in which the urge can be explored rather than enacted or suppressed. ‘Was I right to touch them?‘ is worth asking, but so is ‘what was influencing me in that moment?‘

Whether you reach for a hand or pass the tissues, the question is live each time: can you distinguish your patient’s need for contact from your own need to provide it? And what aspects of the unfolding process might be foreclosed as a result?

Dr. Eddie Jacobs and Dr. Bryony Insua-Summerhays

Ethics Corner Writers

Thank You for Reading

Our next Issue will be published in April. Join our free newsletter to make sure you receive it:

Thank you for reading our third Issue!

Josh Hardman and Alice Lineham

The Editors, The Psychedelic Practitioner